Featuring interviews with Edward R. Carr (Clark University), Mathew Barlow (UMass Lowell), Robert Lempert (Pardee RAND Graduate School), Alan Jenn (University of California, Davis), and Elisabeth Gilmore (Carleton University)

By Stacy Morford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. All photos provided by The Conversation from various sources.

Reading the latest international climate report can feel overwhelming. It describes how rising temperatures caused by increasing greenhouse gas emissions from human activities are having rapid, widespread effects on the weather, climate and ecosystems in every region of the planet, and it says the risks are escalating faster than scientists expected.

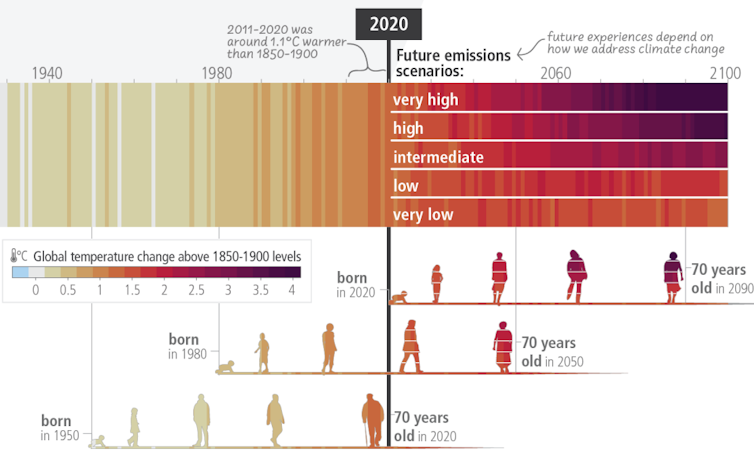

Global temperatures are now 1.1 degree Celsius (2 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than at the start of the industrial era. Heat waves, storms, fires and floods are harming humans and ecosystems. Hundreds of species have disappeared from regions as temperatures rise, and climate change is causing irreversible changes to sea ice, oceans and glaciers. In some areas, it’s becoming harder to adapt to the changes.

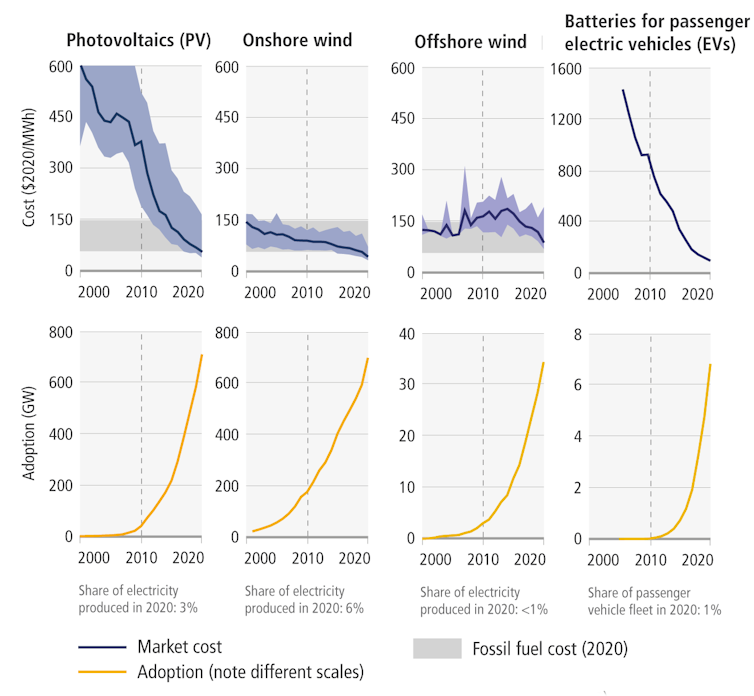

Still, there are reasons for optimism – falling renewable energy costs are starting to transform the power sector, for example, and the use of electric vehicles is expanding. But the change isn’t happening fast enough, and the window for a smooth transition is closing fast, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report warns. To keep global warming below 1.5 C (2.7 F), it says global greenhouse gas emissions will have to drop 60% by 2035 compared with 2019 levels.

That’s 12 years from now.

IPCC sixth assessment report

In the new report, released March 20, 2023, the IPCC summarizes the findings from a series of reports written over the past eight years by hundreds of scientists who reviewed the latest evidence and research.

Here are four essential reads by some of the co-authors of those reports, each providing a different snapshot of the transformational changes underway.

1. More intense storms and flooding

Tom Brenner / AFP via Getty Images

Many of the most shocking natural disasters of the past few years have involved intense rainfall and flooding.

In Europe, a storm in 2021 set off landslides and sent rivers rushing through villages that had stood for centuries. In 2022, about a third of Pakistan was underwater, and several U.S. communities were hit with extreme flash flooding.

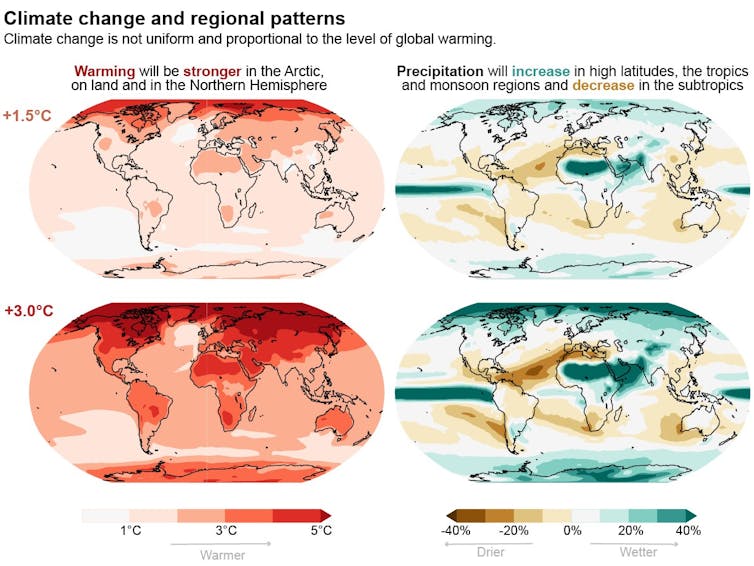

The IPCC warns in the sixth assessment report that the water cycle will continue to intensify as the planet warms. That includes extreme monsoon rainfall, but also increasing drought, greater melting of mountain glaciers, decreasing snow cover and earlier snowmelt, wrote UMass-Lowell climate scientist Mathew Barlow, a co-author of the assessment report examining physical changes.

IPCC sixth assessment report

“An intensifying water cycle means that both wet and dry extremes and the general variability of the water cycle will increase, although not uniformly around the globe,” Barlow wrote.

“Understanding this and other changes in the water cycle is important for more than preparing for disasters. Water is an essential resource for all ecosystems and human societies.”

2. The longer the delay, the higher the cost

Munir Uz zaman / AFP via Getty Images

The IPCC stressed in its reports that human activities are unequivocally warming the planet and causing rapid changes in the atmosphere, oceans and icy regions of the world.

“Countries can either plan their transformations, or they can face the destructive, often chaotic transformations that will be imposed by the changing climate,” wrote Edward Carr, a Clark University scholar and co-author of the IPCC report focused on adaptation.

The longer countries wait to respond, the greater the damage and cost to contain it. One estimate from Columbia University put the cost of adaptation needed just for urban areas at between US$64 billion and $80 billion a year – and the cost of doing nothing at 10 times that level by mid-century.

“The IPCC assessment offers a stark choice,” Carr wrote. “Does humanity accept this disastrous status quo and the uncertain, unpleasant future it is leading toward, or does it grab the reins and choose a better future?”

3. Transportation is a good place to start

Michael Fousert/Unsplash, CC BY

One crucial sector for reducing greenhouse gas emissions is transportation.

Cutting greenhouse gas emissions to net-zero by mid-century, a target considered necessary to keep global warming below 1.5 C, will require “a major, rapid rethinking of how people get around globally,” wrote Alan Jenn, a transportation scholar at the University of California Davis and co-author on the IPCC report dealing with mitigation.

There are positive signs. Battery costs for electric vehicles have fallen, making them increasingly affordable. In the U.S., the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act offers tax incentives that lower the costs for EV buyers and encourage companies to ramp up production. And several states are considering following California’s requirement that all new cars and light trucks be zero-emissions by 2035.

IPCC sixth assessment report

“Behavioral and other systemic changes will also be needed to cut greenhouse gas emissions dramatically from this sector,” Jenn wrote.

For example, many countries saw their transportation emissions drop during COVID-19 as more people were allowed to work from home. Bike sharing in urban areas, public transit-friendly cities and avoiding urban sprawl can help cut emissions even further. Aviation and shipping are more challenging to decarbonize, but efforts are underway.

He adds, however, that it’s important to remember that the effectiveness of electrifying transportation ultimately depends on cleaning up the electricity grid.

4. Reasons for optimism

Ben McCanna/Portland Press Herald via Getty Images

The IPCC reports discuss several other important steps to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, including shifting energy from fossil fuels to renewable sources, making buildings more energy efficient and improving food production, as well as ways to adapt to changes that can no longer be avoided.

There are reasons for optimism, wrote Robert Lempert and Elisabeth Gilmore, co-authors on the IPCC’s report focused on mitigation.

“For example, renewable energy is now generally less expensive than fossil fuels, so a shift to clean energy can often save money,” they wrote. Electric vehicle costs are falling. Communities and infrastructure can be redesigned to better manage natural hazards such as wildfires and storms. Corporate climate risk disclosures can help investors better recognize the hazards and push those companies to build resilience and reduce their climate impact.

“The problem is that these solutions aren’t being deployed fast enough,” Lempert and Gilmore wrote. “In addition to pushback from industries, people’s fear of change has helped maintain the status quo.” Meeting the challenge, they said, starts with embracing innovation and change.

Editor’s note: This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation’s archives.

![]()

Monday, March 20, 2023 in The Conversation

Share: Twitter, Facebook