By Elizabeth Howell

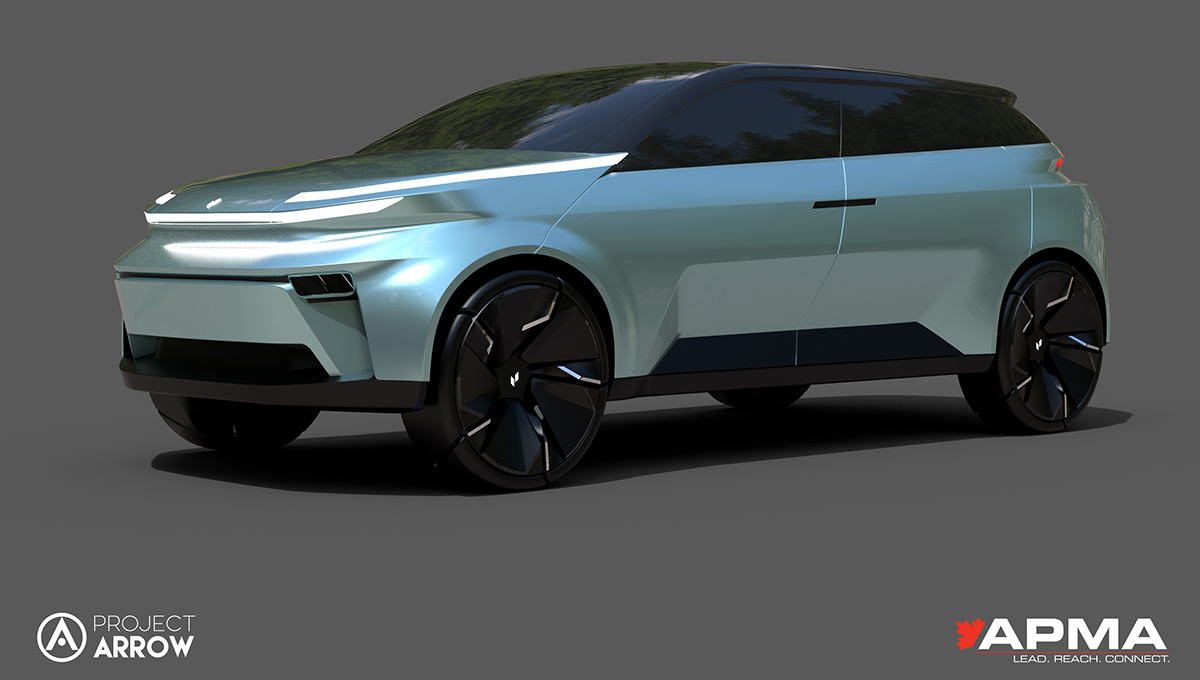

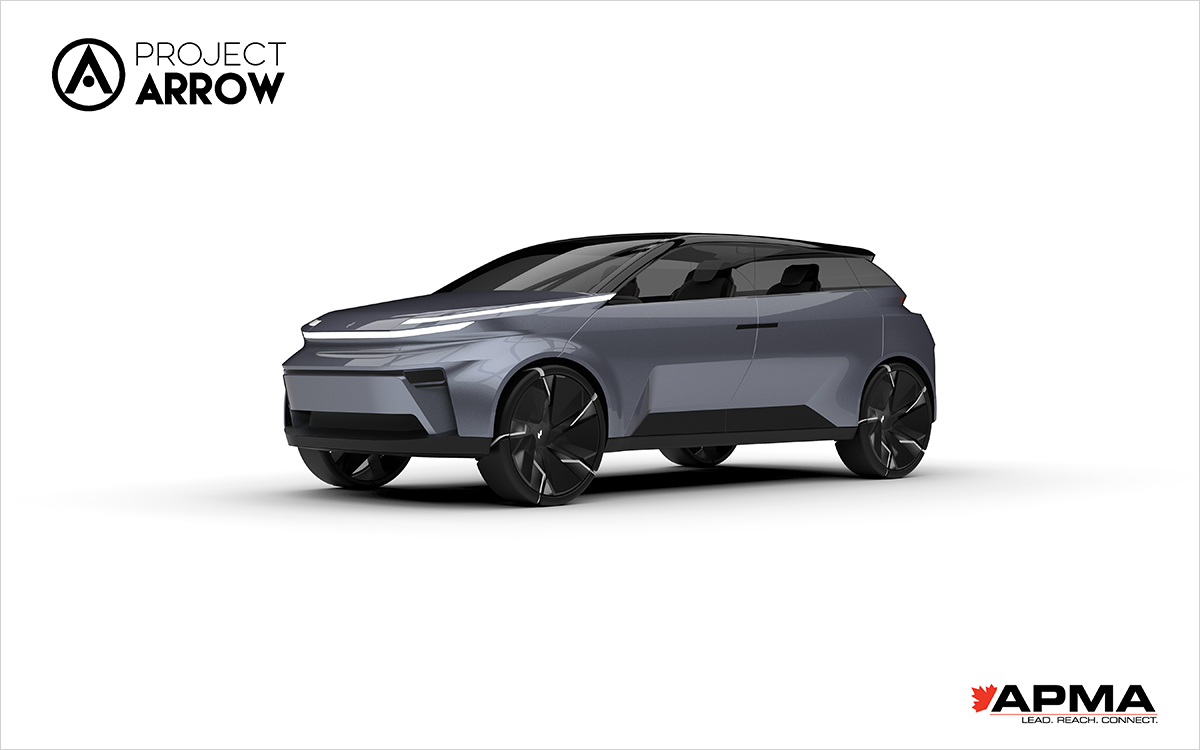

A Carleton University Industrial Design student team won the national Automotive Parts Manufacturers’ Association (APMA) Project Arrow competition, designing a zero-emission concept car using tools such as virtual reality and online communication platforms.

The students had originally planned to meet regularly in person, sharing sketches and sculpting physical models, but quickly pivoted to online tools after the COVID-19 pandemic erupted in Canada in March.

Congratulations to the @APMACanada and the winning team from Carleton University on this all-Canadian zero-emission vehicle design! https://t.co/d5VpAIwVhH

— Justin Trudeau (@JustinTrudeau) October 13, 2020

“This is a proud and historic moment for Carleton University and its Industrial Design students, Kaj Hallgrimsson, Jun-Won Kim, Mina Morcos, and Matthew Schuetz, to have their design chosen as a lighthouse for Canada’s shift into zero-emission vehicle development,” says Colin Singh Dhillon, CTO of the APMA.

“The level of learning and growth must have been ‘off the charts’ for all the students.”

The design brief of the APMA competition was to create a car that could be used in 2025, using zero emissions and also integrating design from Canadian icons and symbols.

The Carleton students spent hundreds of hours thinking through usability and the best way to represent Canadian values in terms of product design semantics. They chose to adopt imagery reminiscent of the pathways carved through the rocks of the Canadian Shield that drivers see all over the country, including on the outskirts of Ottawa.

“We did some research on what Canadian values are and narrowed it down to three key words: freedom, stability and simplicity,” says Morcos. “It wasn’t just something we used when designing the aesthetics of the car, but also its usability and functions.”

The design portion of the competition included two phases. The first phase was an ideation and concept phase that lasted 12 weeks, when the students needed to deliver photo-realistic images to the judges. Then the three shortlisted finalists, including Carleton, were given another 12 weeks to complete the final computer-aided design phase with assistance from Autodesk Technology Centres—where they were placed as part of the company’s distinguished resident program.

Working Together During COVID

The Carleton team, who are third- and fourth-year students, did the work in their spare time while continuing to complete courses and work on internships—all while the world was coping with quarantines related to the pandemic.

“It was challenging to design the whole thing initially, because we couldn’t see each other due to COVID,” says Hallgrimsson.

“So instead of meeting in person, we switched to Zoom conferences. Jun and I would draw while Matt and Mina used VR headsets to quickly 3D sketch new updates and ideas for the design as a wireframe. We would take all that information, iterate and build geometry around it and meet again to share progress.”

Hallgrimsson says the students rapidly divided tasks and kept iterating, week after week. “We all designed the vehicle as a group from start to finish, sketching, modelling, rendering and brainstorming together. But in order to finish the presentation materials in time, we divided some of the CAD work toward the end.”

“This was an extracurricular project the students did on their own accord, which makes it so impressive,” says Bjarki Hallgrimsson, director of the Industrial Design program and father of Kaj. “The students’ work shows the influence of the education and training they received in the program. The mindset of Carleton students is very ambitious. Their mindset is very centred in holistic thinking, working on the problem to be solved rather than just styling or manufacturing some other aspect.”

Judges Impressed with Realistic Approach

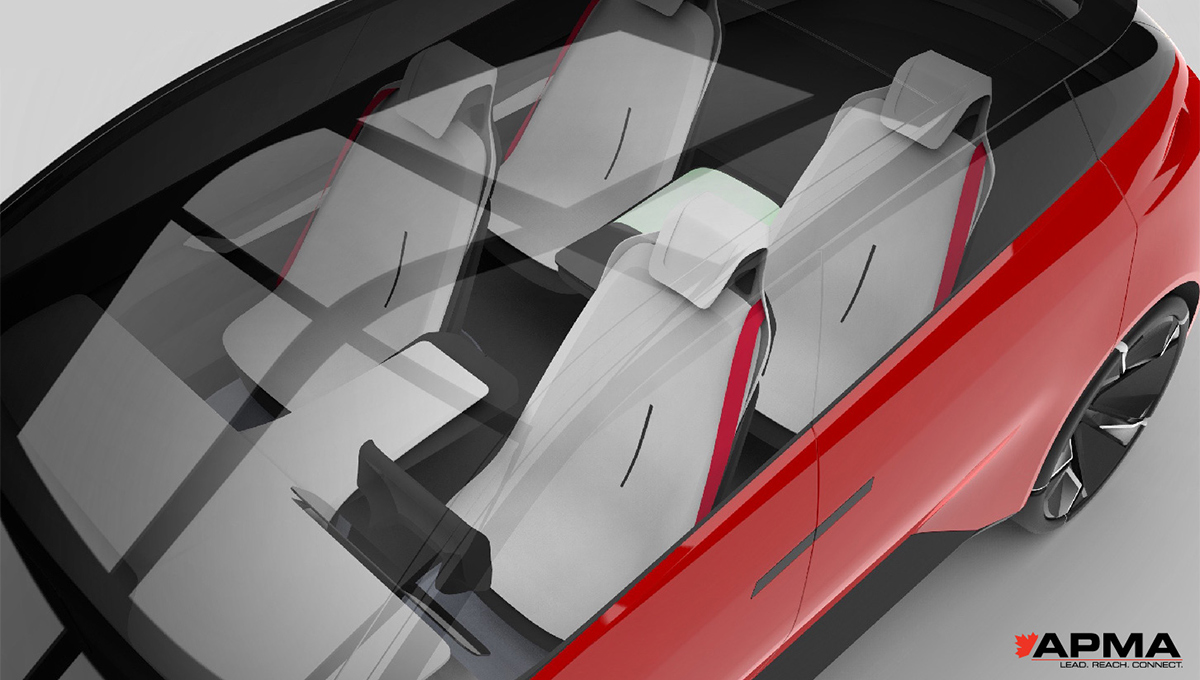

The students were not specifically trained in automotive transportation design before embarking on their project, but took the principles of user-centred design thinking that Carleton’s Industrial Design program instils in its students. For example, the students created accessible seat designs as part of the vehicle to accommodate users who may require wheelchair transfer assistance.

“The competition wanted students to explore vehicle types and try to create our own visions for success. We ultimately landed on a mid-sized SUV, because the market for SUVs is increasingly growing here,” says Kaj Hallgrimsson. “This size vehicle can fit most lifestyles in Canada, (it’s) adaptable for harsh weather conditions and for the needs of both families and smaller households, (and) we paid attention to how each might use the car differently.”

Schuetz explains that the team focused on designing for user interaction instead of just aesthetics. “When we presented our concept to Autodesk, we could see on their faces that they could imagine being behind the wheel themselves because of our realistic approach,” says Schuetz. “The vehicle was not just a space-age concept that only we four designers could imagine.”

Having 24 weeks—the equivalent of two university semesters—to work on the project was a new experience for the students, who were used to working on much smaller group endeavours. “We used skills from our program such as manufacturability, human-centred design and aesthetics. We also had to learn to communicate well if we disagreed,” says Kim.

According to Morcos, the key to strong communication was to learn how to dynamically assign roles as the team evolved the design. Usually on smaller Carleton projects, the students have fixed responsibilities to finish their term projects. But in the longer push to finish the APMA design, the students found themselves adjusting as design ideas and issues came up.

“We were able to use what we learned in class and design at a human scale, which allowed us to create something with more depth and familiarity than some of the concepts produced by professional transportation designers,” says Morcos.

Carleton administrators also came together to support the students as they worked through the project, which ties directly to the university’s new Strategic Integrated Plan that emphasizes preparing students for the future and addressing pressing social issues with a global and sustainable mindset.

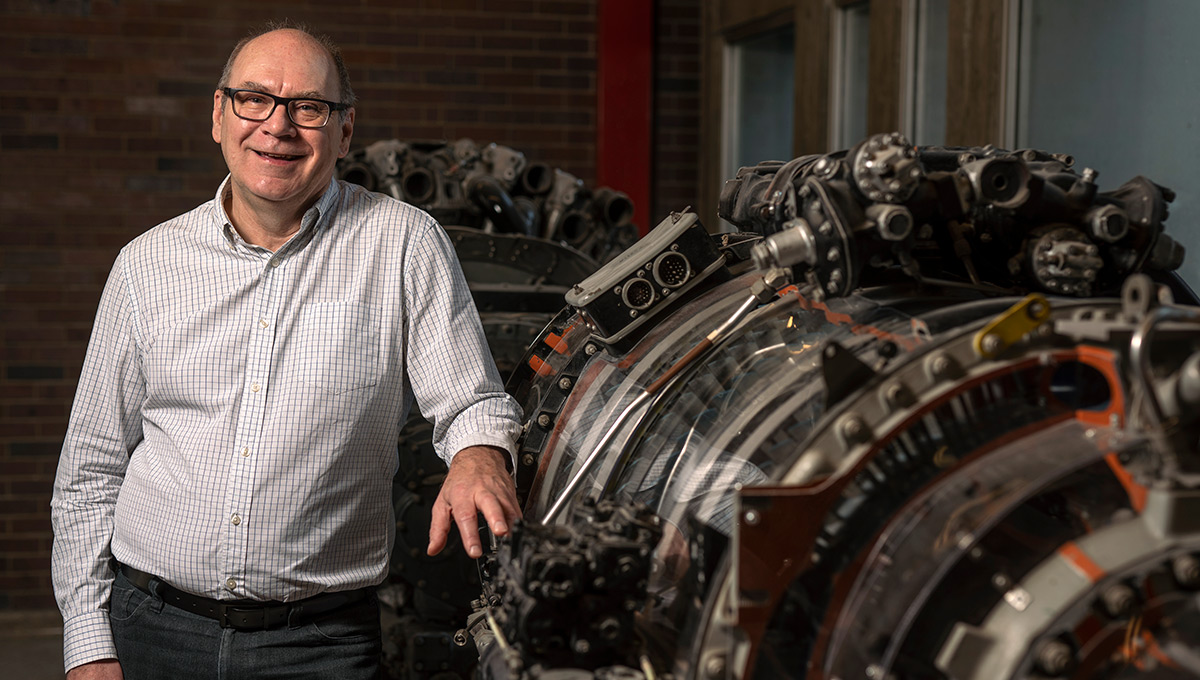

Larry Kostiuk, Dean of Faculty of Engineering and Design

Larry Kostiuk, dean of the Faculty of Engineering and Design, helped the students acquire the insurance they needed to participate in the final stages of the competition, as they were integrated into the Autodesk team. The students also received a lot of support from Carleton’s Tony Lackey, the risk assessment officer for COVID-19, to make sure they had the tools they needed to complete the work.

“It’s just amazing how everybody stepped up to the plate and supported these students, and the students delivered such incredible work in response,” says Bjarki.

“This competition provides further evidence of the excellence of our program, and how it stands out by teaching students to engage with big, real-world problems so as to influence meaningful change for the planet.

These students clearly committed their hearts and souls to the cause of designing the first zero-emission vehicle to be produced in Canada. I am so proud of them, and the hard work they put into this competition.”

Tuesday, October 13, 2020 in Awards, Faculty of Engineering and Design, Industrial Design

Share: Twitter, Facebook