By Dan Rubinstein

Photos by Chris Roussakis

In 2002, after a series of logging blockades drew international attention to the destruction of the old-growth forests on their traditional territory, the Haida Nation filed a case with the Supreme Court of Canada, claiming full title to the land and waters surrounding Haida Gwaii — an archipelago off the coast of British Columbia.

That legal challenge will finally be heard in a few months, but over the last 15 years, while gathering evidence to support their argument, the Haida have not sat back and waited for the federal government to determine their fate.

The Council of the Haida Nation (CHN) — the Haida Nation’s governmental organization, which represents the roughly 3,000 Haida who live on Haida Gwaii and another 3,000 who live off the islands — has been negotiating with both the federal and provincial governments, and with agencies such as Parks Canada and commercial logging companies, and enacting policies and legislation that shape the lives of its people on the islands.

“Our philosophy is to just do it,” said Peter Lantin, president of the Haida Nation.

“Our nation has governed itself for millennia, and today we are transitioning our processes to meet modern challenges.”

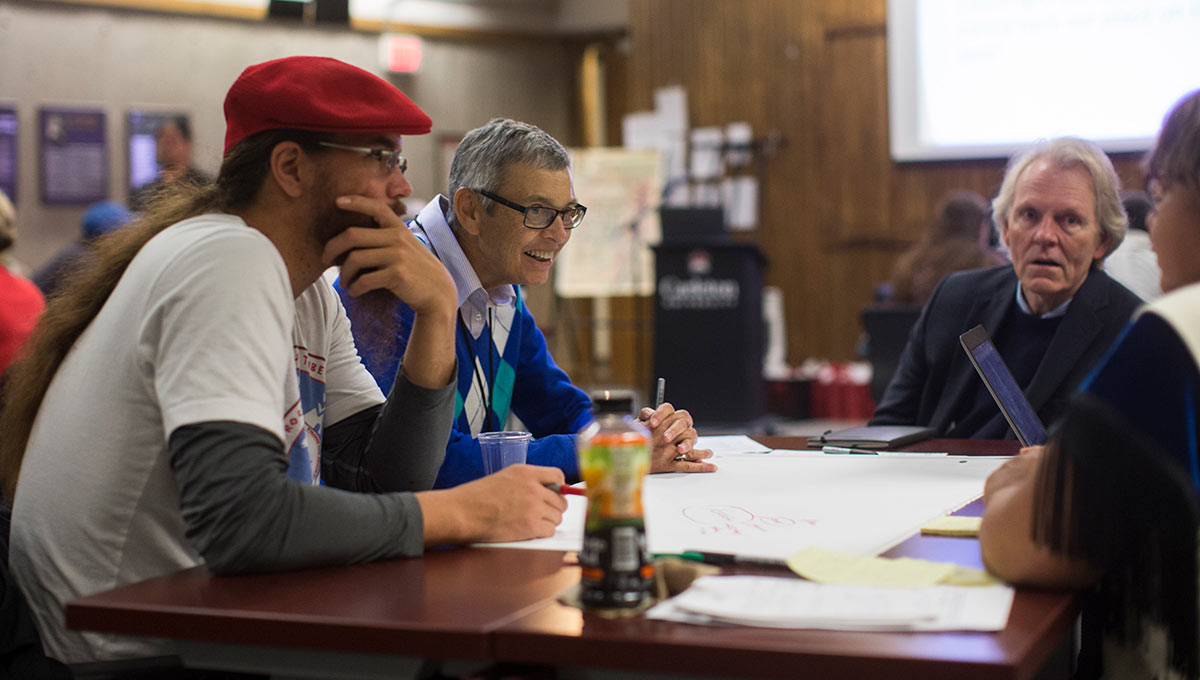

Lantin was speaking at the Transitional Governance Think-Tank, a conference that brought together Indigenous leaders, researchers and policy experts at Carleton University in October. Their discussions focused on how Indigenous communities across Canada can move out from under the Indian Act toward a practical realization of their inherent right to self-government.

“We don’t have to wait for the government or courts to give us a declaration of title,” said Lantin, who studied journalism at Carleton for a couple of years in the early 1990s. “That’s our mindset. And our main job as an organization is to improve the socio-economic well-being of our people, and see how we can make their lives better.”

That said, Lantin concedes that as the Haida court case progresses, and as CHN evolves as an entity, the transition of its governance is a dynamic and ongoing process, as it has been historically.

Which is why — even though the Haida Nation is unique: an isolated homeland with no overlapping land claims — there is great value in coming to gatherings such as the Transitional Governance Think-Tank with other Indigenous communities working toward self-government.

“The path we’re on can feel very lonely at times,” says Lantin, “so it’s important to share experiences, stories and ideas with others who are on the same journey.”

Engaging in Change

The conference that Lantin attended is part of the Transitional Governance Project, a collaboration between the Centre for First Nations Governance (CFNG), the Institute of Public Administration of Canada (IPAC) and Carleton’s School of Public Policy and Administration (SPPA).

SPPA Prof. Frances Abele, CFNG Senior Associate Satsan (Herb George) and Catherine MacQuarrie, IPAC’s senior executive in residence, Indigenous Government Programs, proposed the gathering and moderated most of the sessions.

Their overarching goal is to “build an enduring research and practice partnership between scholars, students and public service partners” and work with First Nations in developing a “versatile transitional governance model that can show what is possible and demonstrate the steps to getting there.”

The roots of the project can be traced back about a decade, when Satsan — a Wet’suwet’en hereditary chief of the Frog Clan and two-term regional chief representing B.C. at the Assembly of First Nations — asked Abele to conduct a systems analysis of the Indian Act.

Her 2007 paper, “Like an Ill-Fitting Boot: Government, Governance and Management Systems in the Contemporary Indian Act,” the product of a winter spent deconstructing the legislation, confirmed to Abele the “horrible history of displacement and conquest crystalized inside the act,” regardless of how many adjustments have been made over the years.

The Indian Act, she argues, imposes top-down authority, fiscal control and law enforcement, and leaves little room “for the basic features of modern government” — such as policy development, management accountability and citizen engagement — in Indigenous communities.

“First Nations citizens and societies have been living under these conditions — and, for decades, very personal controls — for at least eight generations,” says Abele.

“No other group of people in Canada has been subject to such legislation, except incarcerated convicted criminals.”

The contemporary Indigenous rights movement, however, is beginning to turn the tide. From mounting efforts to ensure environmental stewardship of their lands to sustainable development of natural resources, led by a growing group of university-educated leaders and activists and a generation of youth that’s plugged into the world via social media and simultaneously re-establishing connections to traditional practices, many Indigenous communities see self-government as a practical — and feasible — next step.

“Ultimately, the responsibility is ours,” says Satsan. “Nobody is going to do this for us.”

Indigenous Communities Learning From Each Other

Kent McNeil, a professor emeritus at Toronto’s Osgood Hall Law School, who has decades of experience researching Indigenous land rights, treaty rights and self-government, spoke at an opening-day session focused on the constitutional and legal principles arising from Section 35 of the 1982 Constitution Act, which declares that “existing Aboriginal and treaty rights of the Aboriginal people in Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed.”

This clause, said McNeil, gives Indigenous communities “a full box of tools they can exercise without anybody’s permission,” noting that while federal and provincial laws can infringe upon these constitutionally protected rights, the infringement has to be justified by legal precedent, and the bar for that is very high.

“What’s important now is capacity building,” said McNeil.

“You can’t just instantly transform from the Indian Act to full self-government. First Nations can do this incrementally, maybe starting with family matters, inheritance laws, these kinds of things.”

One conference participant interjected, relaying a story about having to get a lawyer and fight for permission to speak at a custody hearing for her grandchild — an example of the conflict between Canadian law and Indigenous culture and tradition, which recognizes a grandparent’s right to be heard.

“Under a system of self-government, these types of situations would be settled in your community, within your laws and culture,” responded McNeil.

“There’s a window of opportunity now because we have a federal government that’s sympathetic,” he continued. “And, in a sense, they’re not sure what to do and are looking for guidance.”

McNeil was followed by Emmanuel Brunet-Jailly, a political scientist at the University of Victoria’s School of Public Administration. His presentation addressed the fiscal intergovernmental relationship between First Nations and Ottawa, a system he described as “basically a straightjacket — it holds a lot of different bands in a straightjacket, and prevents a lot of things from happening.”

The federal government has a pattern of delegating powers but not resources, he said, which downloads costs onto First Nations without the monetary resources to tackle their social and economic needs or operate within the global economy.

But there are steps that First Nations are taking, said Jailly, such as administering property taxes and pooling resources with other communities — a shift that must start with developing knowledge and training people, which reflects McNeil’s call for capacity building and incremental change.

Hearing the Land Speak

On the second day of the conference, in a session called “Lessons from the Land,” Indigenous leaders from “highly self-determining” communities shared their practices, approaches and insights from the frontlines of the self-government movement.

Chief Connie Lazore, who represents the Tsi Snaihne District on the Mohawk Tribal Council, told the gathering that she earned a graduate diploma in Indigenous Policy and Administration at Carleton “to help understand my role as a leader and to build capacity within myself, so I could offer it to my community.”

Her community straddles the borders between Ontario, Quebec and New York, which presents jurisdictional challenges — for example, when people have to cross an international boundary to travel from home to work.

There is no forestry or mining to regulate in the Akwesasne Territory. One of the pressing environmental issues involves erosion from the ship traffic in the St. Lawrence Seaway.

“You have to understand your own community, and its needs, before you can tell Canada what you want,” said Lazore, noting that this requires widespread consultation and communication with community members, and a commitment to transparency and accountability.

Lazore was followed by John B. Zoe, a senior adviser to the Tlicho Assembly, which has governed the Northwest Territories nation since its combined comprehensive land claim and self-government agreement were signed in 2005.

Zoe, who has served in an incredible range of roles in his community, from translator and engineer to executive director and land claims negotiator, recalls being told by Elders to spend more time on the land. “That’s who we were,” he said, “and what we’re now trying to achieve is an extension of who we were.”

Canada’s history is a saga of settler institutions — companies and governments — exploiting the land to extract resources, said Zoe. Indigenous communities are in the process of subverting this top-down approach, and using their land titles to develop sustainable revenue streams that can be allocated toward addressing social issues such as health care and education.

“We can’t win all the battles,” said Zoe, “but over time, as the authority we have is recognized, there will be openings and opportunities.”

Lantin was part of the session with Lazore and Zoe, and like the other two leaders, he talked about the importance of education.

“In this world of self-determination, taking charge of education and teaching our young people is the most important thing we can do,” he said. “We need to ensure that young people are informed and involved in decision making.”

On Haida Gwaii, Lantin said, there’s a generation growing up that has never lived on the “Queen Charlotte Islands,” the name applied to the islands by Britain in the mid-1800s.

“We’ve made a significant journey in a short period of time,” he said, “but we still have a very long way to go.”

Wednesday, November 8, 2017 in Government, Indigenous

Share: Twitter, Facebook