By Dan Rubinstein

Photos by Chris Roussakis

Cans of paint and ink, jars full of brushes, silkscreen frames and squeegees and stacks of canvas rectangles are in position atop plastic-covered tables in Carleton University’s Fenn Lounge on a cold and sunny weekday morning.

A couple dozen students are sketching designs on long sheets of paper, mapping out the silkscreen banners they’re making alongside renowned Métis artist Christi Belcourt and Ojibway artist Isaac Murdoch.

Belcourt’s national touring exhibition, “UPRISING: THE POWER OF MOTHER EARTH,” a retrospective with Murdoch, has just opened at the Carleton University Art Gallery (CUAG), and this participatory art-making workshop is part of her approach to blending art and activism.

“These banners are going to be sent — for free — to water protectors and land protectors,” Belcourt tells the students.

“This is what we love to do. This is what we have to do. They’re on the front lines, putting their bodies on the line for us.

Christi Belcourt and a student work on a silkscreen frame.

“The opening at the gallery last night was fun, but this is more fun. This is how we build community.’

“We only have five hours, but there’s no reason we can’t make a few hundred,” adds Murdoch, advising that an “assembly-line mentality” will be required to produce banners without letting the screens dry.

“It feels really good to contribute to front-line actions around Canada and the United States. This is the very least we can do.”

Belcourt explains what needs to be done — unwrap bags of canvas, water down paints, six people over here, four people over there — and with little direction, people seamlessly move into their stations and get to work.

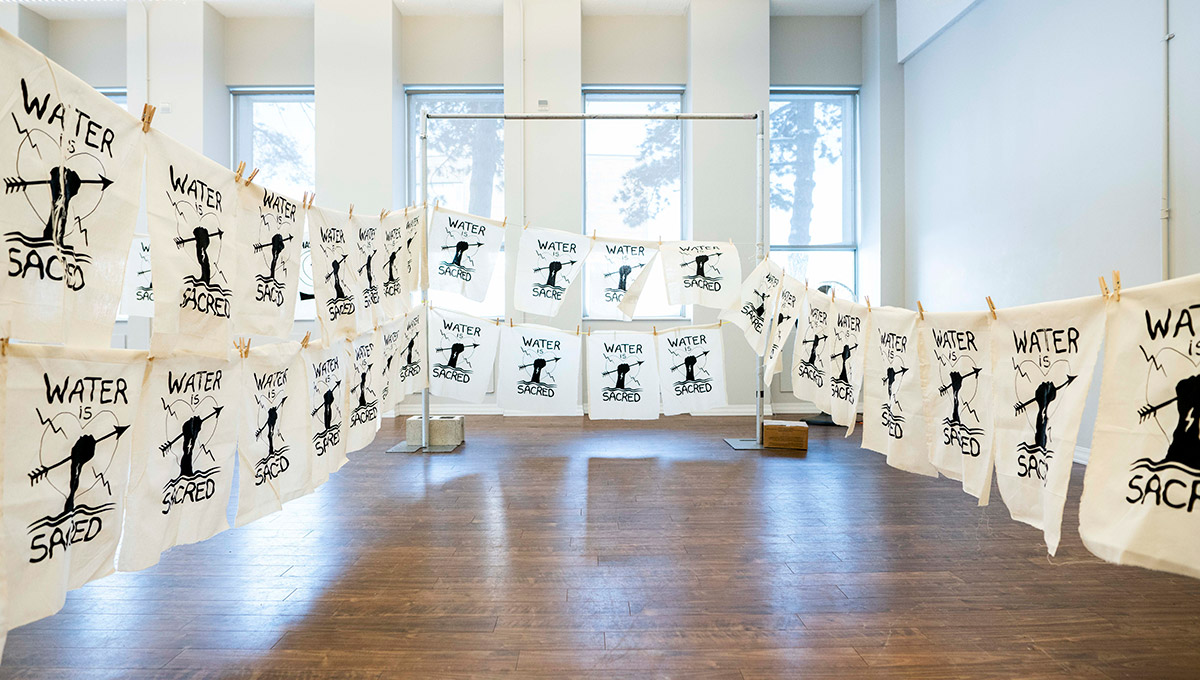

Within minutes, black ink on white canvas banners with a Belcourt-designed image of a fist holding an arrow and the words “water is sacred,” and other banners with similar slogans accompanying the artists’ designs, are hung on lines to dry.

More and more students and community members arrive and join in, and the number of banners flapping in a breeze whipped up by a couple of large fans quickly approaches a hundred.

Exploring the Traditions of Indigenous Art

“UPRISING: THE POWER OF MOTHER EARTH,” which is co-produced by the Thunder Bay Art Gallery and CUAG, will remain on display until the end of April.

Much of the exhibition consists of large, colourful beadwork-like textured acrylic paintings featuring iconic natural images (flowers, roots, birds, fish and other animals), as well as more abstract aquatic landscapes.

It includes more than 30 major Belcourt paintings, some of which are darker than others, such as “Bloodletting: Does This Make You More Comfortable with Who I Am?” (2004), a dramatic self-portrait in which the artist challenges viewers to question their assumptions and beliefs about personal and cultural identities.

“Like generations of Indigenous artists before her, the majority of her work explores and celebrates the beauty of the natural world and traditional Indigenous worldviews on spirituality and natural medicines while exploring nature’s symbolic properties,” reads Belcourt’s official bio on her website.

Isaac Murdoch

“Following the tradition of Métis floral beadwork, Belcourt uses the subject matter as metaphors for human existence to relay a variety of meanings that include concerns for the environment, biodiversity, spirituality and Indigenous rights.”

Belcourt, whose work is in the collections of institutions such as the National Gallery of Canada, Art Gallery of Ontario and Canadian Museum of History (all of which loaned paintings to “UPRISING”), has a long list of accomplishments as an artist.

Her stained-glass work “Giniigaaniimenaning (Looking Forward)” was created “to commemorate the resilience and strength of residential school survivors and their descendants,” according to her website, and was permanently installed above the main entrance for MPs in Centre Block on Parliament Hill.

She also designed the competition medals for the 2015 Pan Am and Parapan Am Games in Toronto, and is the founder and lead co-ordinator of “Walking With Our Sisters,” a community-driven project that honours missing and murdered Indigenous women and was presented at CUAG in 2015.

“The thing that we enjoy the most is working with community, and having people come out and participate in creating art to try and save the world,” Belcourt told CBC when “UPRISING” opened at the Thunder Bay Art Gallery in June.

“We want people to come out of here feeling empowered and feeling like they really are a part of this Earth and that it’s worth fighting for.”

Fighting for Indigenous Rights

The exhibiion by Belourt and Murdoch, who comprise the Indigenous artist and environmentalist Onaman Collective with Erin Konsmo, opened alongside another CUAG exhibition rooted in Indigenous activism.

“My Mom, kahntinetha Horn, the ‘Military Mohawk Princess,’” curated by Carleton Indigenous and Canadian Studies Prof. Kahente Horn-Miller, presents a series of photographs of kahntinetha Horn — a model and actress who became an activist and leader and worked as a public servant in what was then the federal Department of Indian and Northern Affairs.

There are photos of Horn when she was crowned the 1963 “Indian Princess of Canada” by the National Indian Council, where she served on the doard of directors; outside 10 Downing Street when she went to London to try to deliver a letter to the Queen; being arrested at a protest on the Canada-U.S. border in 1968; images of Horn on The Dick Cavett Show and doing a news conference on Parliament Hill, among others.

Prof. Kahente Horn-Miller

Horn-Miller’s exhibition came about last year as a result of a chapter about her mother that she was writing for a book on Indigenous celebrity, edited by former Carleton Prof. Jennifer Adese, Carleton’s Zoe Todd and University of Saskatchewan Prof. Robert Innes.

She was doing research, interviewing her mother and sisters, and wrote a Facebook post that caught the eye of CUAG Director Sandra Dyck, who asked Horn-Miller if she wanted to curate an exhibition. The answer was an immediate yes.

“I’ve been doing a lot of thinking about how my mother’s story gets passed on,” says Horn-Miller, explaining that it was only in 1990, during her family’s participation in the land dispute known as the Oka crisis, that her mother became more open about her activism. “She had put it aside to raise her kids. At Oka, she re-emerged onto the Indigenous rights scene.

“This idea — putting aside your actions to raise kids — really speaks to my mother’s motivation. She was doing it for the young people. She wasn’t a lone voice, but she was pretty loud.”

Horn, whose father was an ironworker who worked in New York City, started to model in part to make money to fund her work to address what Horn-Miller calls “the issues that she saw around her.”

Horn’s grandparents helped raise her and her siblings, teaching them their traditional Kanien’kehaká (Mohawk) language, “which gave her a true sense of who we are as Indigenous people,” says Horn-Miller, “and how grounded we are in terms of our relationship to the land.

“My mother understood her responsibility to her people, and that motivated her activism” — a role that included being “a thorn in the side of government” during her career at Indian Affairs, compelling Ottawa to pay attention to issues such as the dangers of cold water drowning (which is significant in communities where people fish and hunt to feed their families) and the forced sterilization of Indigenous women.

“We are her greatest legacy — she has four daughters who are doing different and diverse things,” continues Horn-Miller, noting that her sisters are a medical doctor, an Olympian and health advocate, and an actress.

“We are doing what we can for future generations.”

Just as her mother did. Just as artists such as Belourt and Murdoch do.

Click here for more stories from the Carleton Newsroom.

Thursday, January 24, 2019 in Art Gallery, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Indigenous

Share: Twitter, Facebook