By Lowell Gasoi

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. All photos provided by The Conversation from various sources.

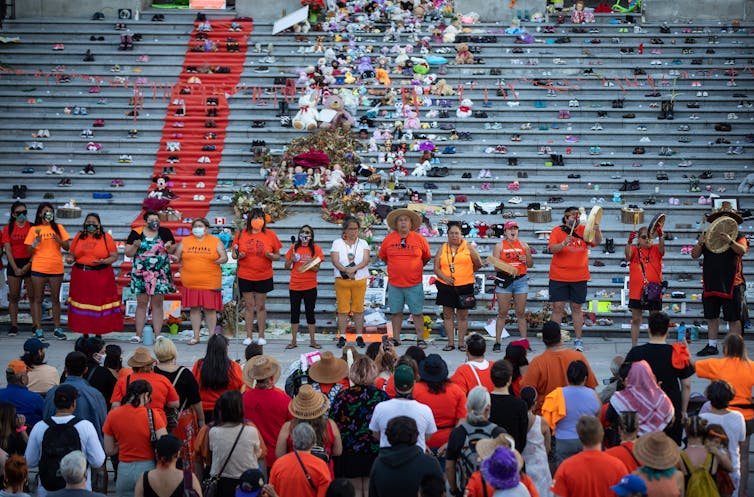

The recent discoveries of remains at the sites of former Indian Residential Schools in Kamloops, B.C., Brandon, Man.,, Cowessess, Sask., and Cranbrook B.C. have forced many Canadians to confront the horrors of brutal mistreatment and the ongoing oppression of Indigenous people.

The reactions to this discovery have ranged from expressions of shock and grief to resignation and even cynicism. The sad and painful truth is these are not the first, nor will they be the last of such discoveries.

As a communications scholar and white settler in Canada, my privileged place requires that I assume a responsibility to critically interrogate a pattern that appears in the aftermath of these discoveries. It is a pattern we continually see.

People from communities impacted by these events, along with advocates and politicians from all sides, call for action. Almost invariably, that call will also decry the emptiness of “more words.”

Words are actions

Following the discovery in Kamloops, NDP leader Jagmeet Singh said, “I want us to move on from symbolic gestures and nice words that the Liberal government has done again and again. We need concrete action.”

These statements suggest that words and action are separate things and that one must replace the other. This idea is a danger to our democratic response to violence and oppression. Because words, images and symbols are how we share experiences. They’re how we learn to live with those who have different beliefs than us. They give us a way to resolve those differences not through violence, but through a shared language.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl Dyck

As philosopher Hannah Arendt wrote, democratic power works “only where word and deed have not parted company.” Words are the fundamental building blocks of our laws and policies. Actions shape the world, as do words. In this sense, words are actions. Suggesting that words pale in comparison to action is building an apathy and cynicism that is infecting Canadian democracy.

How to do things about oppression

The old playground adage about sticks and stones has been proven time and again to be patently false. Words can hurt us.

People from marginalized communities are particularly aware the power words have and the damage they can do – so much so that we have rightly censured people in power who wield words to inflict violence.

Philosophers of language like J.L. Austin have theorized the ways these words “do things.” In other words, they don’t only represent or describe things but create and enact things — they are what theorists call a “performative.”

Austin uses the example of “I do” at a wedding ceremony. Saying those words, he argues, at the appropriate time and in the proper context, creates a marriage, with all the rights and responsibilities, legal and social, that attends to that union.

Austin’s work has been critiqued and elaborated on by many, including feminist legal and rhetorical scholar Judith Butler. In her groundbreaking work Gender Trouble, Butler argues that performativity is much more present than we think, even in supposedly constative statements (something that is either true or false).

She says that a doctor’s declaration, “it’s a boy,” during the birth of a child would appear to be a description of the child’s gender. But really gender itself is a performance, an array of social and political behaviours that can be subverted and challenged.

“It’s a boy” does not lock a human into a described social existence, but rather places certain expectations onto the child about how they will behave, expectations which that child may later challenge.

Separating words from actions

Marianne Constable, a professor of rhetoric at Berkeley, employs Butler’s ideas in her critique of former U.S. president Donald Trump. Constable explains how Trump’s refusal to name his order to “ban” travel from majority-Muslim countries a “ban,” made it difficult for media and advocates to challenge this speech act.

By tweeting “Call it what you will,” and then ordering his press secretary to advise reporters not to call his order a “ban,” he divorced the word from its meaning. The resulting actions on borders and at airports were confusing and sometimes violent, as well as being hard to challenge in court.

Constable writes that separating words and actions is “problematic because the actions of Trump, as head of state, are matters of law that are done, more often than not, precisely through words.”

(Mike Von/Unsplash), CC BY

Words can do harm but also heal

These are the dangers of performative words, but words as actions can also have positive impacts.

In the wake of these tragic discoveries by Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc and Cowessess First Nation, many words were spoken and symbolic actions taken. Flags were lowered, debates occurred in the House of Commons, apologies were offered and celebrations are being reconsidered.

While some may decry these words and symbolic acts as “performative,” we need to ensure it is not as a dismissal of the actions altogether, but part of a way forward that is possible through sharing words.

An apology by a prime minister, an admission of culpability in words, may have legal consequences that lead to redress and compensation.

As Angela White, director of the Indian Residential School Survivors Society, said in response to statements from the government and the Church: “Reconciliation does not mean anything if there is no action to those words.”

While acknowledging that reconciliation itself is a performative word, White is saying that coupled with action it can lead to ongoing changes to laws, funding, relationships and knowledge.

Just a few days after the discoveries in Kamloops, a law was passed allowing First Nations people to reclaim their traditional names on Canadian passports and other official documents. Names —powerful words of identity, family, culture, and belonging that were stripped from Indigenous people — are being returned to them through law.

Austin acknowledges that even performative words can be lies, promises can be broken and marriages can be dissolved. But as Constable writes, “If words promise to reveal the world, then law, one might say, insists that the promise be kept.” Laws can be the words that enshrine our promises to one another, bringing about the actions we seek to promote and protect a common good.

There is still a lot of work needed on the path to reconciliation, but if we accept and encourage instances like these as actions that are part of that important process, we will strengthen our democracy.

Words can challenge the forces of cynicism and apathy that come from the cries that we cannot just keep talking. Talking is what we must do because words are actions and we need them now more than ever.

If you are an Indian Residential School survivor, or have been affected by the residential school system and need help, you can contact the 24-hour Indian Residential Schools Crisis Line: 1-866-925-4419

![]()

Sunday, July 4, 2021 in The Conversation

Share: Twitter, Facebook