By Jena Lynde-Smith

Hearing loss is a common yet often overlooked aspect of aging, with statistics suggesting that most individuals over 50 and nearly all individuals over 70 will experience some degree of hearing impairment.

This issue is not limited to audibility but extends to cognitive function, with hearing loss being one of the highest risk factors for developing dementia.

Imola MacPhee, a clinical audiologist and PhD student in Carleton University’s Department of Cognitive Science, is using brain imaging to reveal how hearing loss affects cognition, particularly in aging adults.

“We want to get to the bottom of how the brain changes when there is hearing loss and how you can decrease your risk of cognitive decline,” MacPhee says.

Imola MacPhee, a clinical audiologist and PhD student in Carleton University’s Department of Cognitive Science (Photo by Brenna Mackay)

Hearing Loss and Dementia

MacPhee’s work takes place in Carleton’s CANAL Lab, alongside lab director and cognitive science professor John Anderson. The lab studies the interaction of lifestyle and contextual factors (e.g., time of day, caffeine, and mood) to help optimize cognitive performance in older adults.

MacPhee is spearheading the hearing loss project to reveal the link between hearing loss and cognitive decline – specifically the development of dementia. To inform her research, MacPhee and Anderson are conducting brain imaging tests at the Royal Ottawa Mental Health Centre.

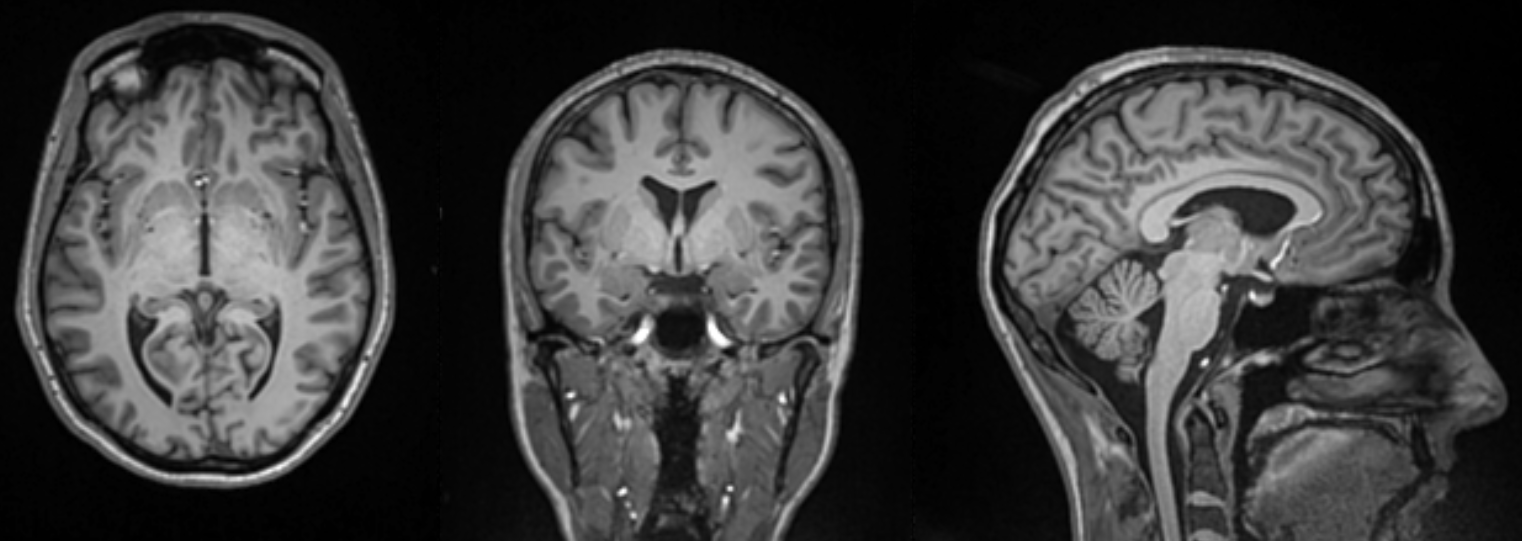

“We use functional MRI, structural MRI and diffusion MRI to observe changes in brain structure, connectivity and activity when individuals engage in various cognitive and hearing tasks,” MacPhee explains.

What they’ve found is an individual’s hearing capacity can affect the brain’s anatomy. One change observed is the thickness of the cerebral cortex – the outer layer of the brain responsible for higher cognitive functions. Cortical thickness has proven to be a biomarker used to predict the progression of dementia.

Some of MacPhee’s tests also include stimulation exercises, where subjects listen to certain sounds while their brain activity is monitored in central areas – such as the auditory cortex which is responsible for processing sound.

“By observing the brain’s response to these stimuli, we can map out the regions of the brain that are involved in auditory processing and how they are affected by hearing loss,” MacPhee says.

Depleting Cognitive Reserve

MacPhee’s work is centered on the concept of cognitive reserve. This theory suggests that certain activities, such as learning a second language and engaging in physical activity, may build a reserve that helps protect against cognitive decline in later years.

“Hearing loss depletes cognitive reserve,” she says.

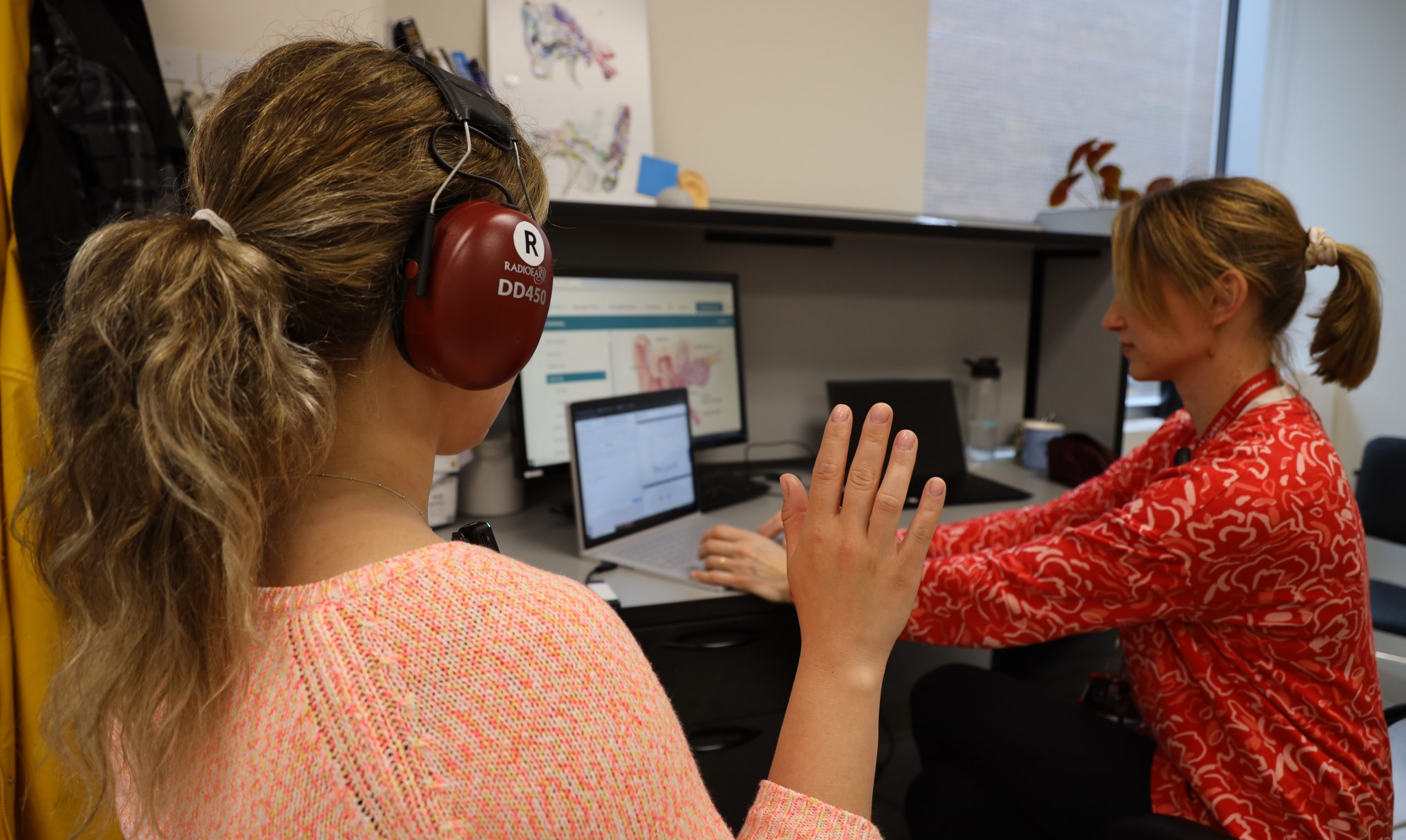

MacPhee’s brain imaging tests are cementing this theory. Currently, the tests are being run on young individuals with normal hearing. To first determine the subjects’ hearing proficiency, MacPhee assesses them using SHOEBOX — a portable audiometer.

MacPhee conducts a hearing test using SHOEBOX, a portable audiometer (Photo by Brenna Mackay)

In the next phase, MacPhee will begin looking at aging individuals with hearing loss. She will then compare data between individuals with and without hearing loss to identify differences that may explain the link between hearing loss and cognitive decline.

“Right now, we are focusing on the foundational science,” she says. “Once we have all of our data compiled, we hope to run trials with hearing aids to show how they may be a preventative measure for dementia.”

In addition to her work on hearing and cognition, MacPhee is part of a project in collaboration with the University of Ottawa focusing on brain fog in chemotherapy-treated breast cancer survivors.

This research is particularly significant as hearing loss is a common side effect of chemotherapy, affecting about 50 per cent of individuals who undergo treatment.

“I happened onto this population who is prone of hearing loss by chance,” she says.

MacPhee plans to compare the data gathered from this research with her findings in the CANAL Lab. This will help her make deductions about the effects of acute, rapid-onset hearing loss versus gradual onset hearing loss on cognitive function.

Abolishing Barriers and Instituting Change

The primary goal of MacPhee’s work is to influence individuals to take their hearing seriously, test it regularly and implement interventions like hearing aids if necessary.

“People don’t think twice about going to get their eyes checked and trying out a pair of glasses, but getting your hearing checked feels like a completely different beast,” she says.

A lot of this reluctance is due to societal stigma, but financial barriers also contribute as hearing tests and aids are not traditionally covered by insurance companies.

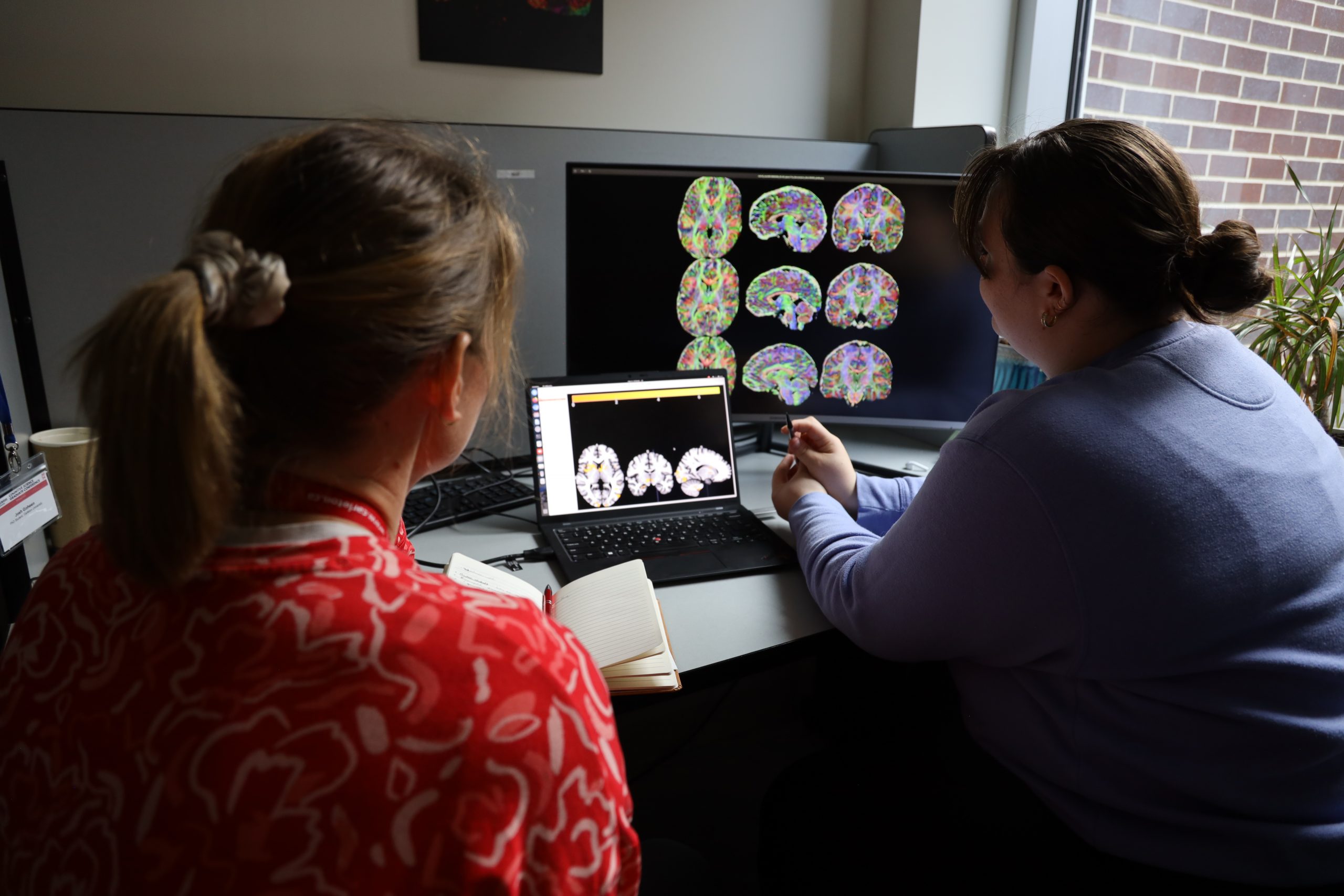

MacPhee and Veronica Cramm, an undergraduate cognitive science student (Photo by Brenna Mackay)

“Not only is it a big adjustment, but if you’re not covered, you will generally end up paying out of pocket to take care of your hearing” says MacPhee.

But things are starting to change. Initiatives such as the Ontario Assistive Devices Program offer benefits to help offset the costs of hearing aids every five years, and many employers – including Carleton – are beginning to cover a portion of hearing aids.

MacPhee hopes that by tying hearing impairment to cognitive decline and dementia, her research will contribute to continued change.

“Even if people’s choices aren’t research-driven day to day, policy can be,” she says.

In terms of everyday care, MacPhee urges people to be mindful of their hearing during any loud tasks.

“When you go to a concert or mow the lawn, put on your earmuffs,” she says. “These are the kinds of things that people don’t realize are an issue until they’re getting their first audiogram at age 65.”

“You only get one set of ears. Knowing what we do now about how it affects our cognition, it’s more important than ever to protect them.”

First and last full width photos from iStock

Thursday, May 30, 2024 in Cognitive Science, Health, Research

Share: Twitter, Facebook