By Dan Rubinstein

Photos by Mario Santana Quintero

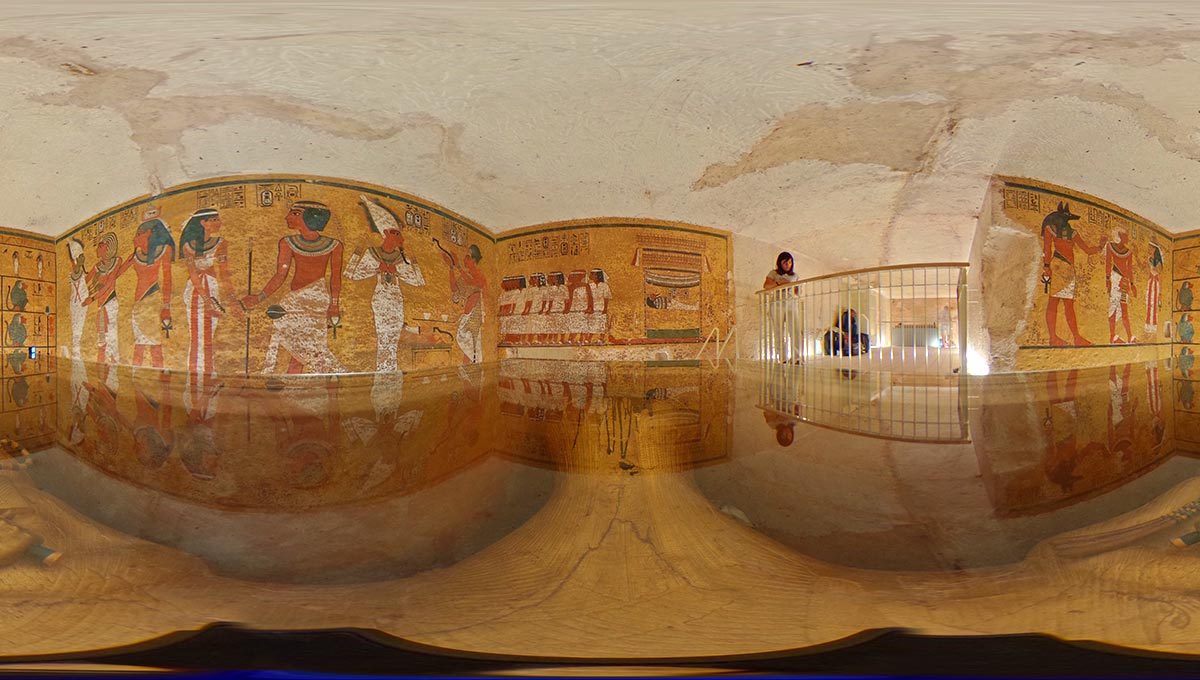

From the subterranean mystique of Tutankhamen’s tomb in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings and the sunbaked 1,000-year-old temples of Bagan, Myanmar, to the ancient homes on Bahrain’s Pearl Road and the earthquake-damaged earthen buildings in Katmandu, Carleton University’s Mario Santana Quintero is painstakingly working to document and preserve some of the world’s most important heritage sites.

Santana Quintero, an Architectural Conservation and Sustainability professor, and his students spend long days in these historic places with conservators from local governments and non-profits such as the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI), laser scanning and taking detailed photographs of the structures and their decorated interiors.

CIMS cotutelle PhD candidate Davide Mezzino demonstrates the latest digital technology.

The images and data they capture with cutting-edge technologies is used to generate digital maps and models that can help guide conservation and restoration efforts, and create immersive virtual tours of the sites.

“In our field, what we try to do is show the processes of decay that are impacting historical structures and surfaces such as painted walls,” says Santana Quintero, who runs the NSERC CREATE Heritage Engineering research and training program out of the Carleton Immersive Media Studio (CIMS).

“To do this, we need to understand the current conditions, and what mechanisms affect these conditions, and at what rate.

“Think about a city,” he continues. “If we replace everything with new buildings, people won’t be able to appreciate the layers of history and evolution. Heritage sites are carriers of knowledge and sense of place, and we need to be careful about how we conserve and protect them. We want them to transcend history and share their stories with future generations.”

Protecting Egypt’s iconic tombs

Last March, Santana Quintero and Heritage Engineering master’s student, Alex Federman, spent nearly two weeks digitally documenting the tombs of Tutankhamen and Queen Nefertari along with the GCI’s Lori Wong, conservation technologist Christian Ouimet from the Canadian government’s Heritage Conservation Services, and staff from Egypt’s Ministry of Antiquities.

These sites, which the GCI began working to protect when their assistance was requested by the Egyptian government, are very significant yet also vulnerable to deterioration, exacerbated by high levels of visitation.

Despite mitigation measures, Tutankhamen’s tomb is vulnerable to damage from visitors.

“Tutankhamen’s tomb is iconic in the annals of Egyptology and archeology in general because of the electric story of it discovery in 1922, and by virtue of the incredible treasures that were found inside,” says Neville Agnew, a senior principal project specialist with the GCI who directs the Tutankhamen project and has been working in Egypt since he joined the institute in the late 1980s.

The impact of visitors includes physical damage from people touching the walls and heat from lighting equipment used by film crews, says Agnew, as well as super-fine dust brought inside and kicked up by visitors, and the atmospheric impacts of humidity and carbon dioxide.

Mitigation measures have been effective. An open grid on the floor near the entrance and a filtered air ventilation system, for example, help minimize dust. A viewing platform was moved to prevent visitors from touching walls.

In Nefertari’s tomb, much of the current documentation work will help conservators establish a baseline of the current condition of the wall paintings — and because the models and data will be available as an archive in the years ahead, they will play a key role in monitoring the condition of the paintings moving forward.

“This is a critical component of any good conservation project,” says Agnew. “It makes it possible to quantitatively say there have been damages or changes, and can help diagnose the cause of these changes.”

High-tech documentation techniques, he adds, make it easier to disseminate and manipulate the information that’s collected, and easier to use it for interpretive or educational purposes.

Agnew, who has led conservation projects around the world, from the Laetoli hominid trackway in Tanzania to the historic city centre of Quito, Ecuador, praises Santana Quintero’s contribution to the work in Egypt.

“He’s an excellent field man — unflappable, cheerful, very imaginative and hardworking,” says Agnew. “He’s also a very patient teacher.”

Hands-on heritage conservation

Federman, who accompanied Santana Quintero in Egypt, is an NSERC CREATE student. The program provides students with hands-on opportunities to work and learn in the built heritage industry in addition to earning a university degree.

It’s a multi-disciplinary program, with opportunities for Carleton students in Engineering, Architecture, Information Technology and Indigenous and Canadian Studies. They learn techniques such as laser scanning and photogrammetry – the science of using photographs to make precise measurements – and how to use integrated surveying instruments such as Total Station.

“Heritage sites are carriers of knowledge and sense of place,” says Prof. Mario Santana Quintero, “and we need to be careful about how we conserve and protect them.”

“To be able to spend so much time in those tombs and appreciate 3,000 years of history was incredible,” says Federman, who took high-resolution photos of the wall paintings and other features, collected metric data to underlay the visual representations, and helped train local collaborators on these documentation techniques.

“Even though we were working, I was able to step back and take it all in. You never know when you’ll have another opportunity like that.

“The state of the wall paintings, in some areas, was remarkably good. And the level of detail on the sarcophagus … I wish I knew how to read hieroglyphics.”

Federman, who will graduate this fall, has allocated about one-third of his master’s thesis to Tutankhamen’s tomb. The rest will cover digital documentation work at Nepean’s Log Farm — a mid-1800s family-farm-turned-sugar-bush just off Highway 416 in southwest Ottawa — and Prince of Wales Fort, an 18th century stone compound in Churchill, Manitoba.

In the summer of 2016, Federman spent four days using a drone to take aerial photos of Prince of Wales Fort to help create a digital model. At the Log Farm, which he visited once each week or two throughout last fall, he has helped create a record of its vernacular architecture, including 3D models, both for posterity and to help direct potential restoration work. The National Capital Commission supported his work at the Log Farm, and the project in Churchill was executed in collaboration with Public Services and Procurement Canada’s Heritage Conservation Services.

“I’ve really enjoyed all of this work — at the local, national and international levels,” says Federman.

“It’s been great because it’s so hands-on, and because I’ve been able to learn from somebody as accomplished as Mario.

“Heritage buildings are our remembrance of times past,” he adds. “We have an opportunity to help them, and they can help us remember.”

Pushing past your comfort zone

Beyond the technical knowledge and professional experience students gain from contributing to projects in Egypt, Myanmar, Bahrain and Nepal, the work gives students invaluable exposure to international collaborations, says Santana Quintero, who has taught at universities in Belgium, the United States, Germany and Japan, and consulted widely in the heritage conservation field before coming to Carleton five years ago.

“When students travel and spend time in different cultures, they’re pushed outside their comfort zones and interact with so many different people in so many different ways,” says Santana Quintero, who was profoundly impacted by his first international exchange as 17-year-old student from Venezuela.

“It can be an intense experience, but it gives you such a feeling of mobility and possibility.

“And it can help you get a job,” he adds, noting that his former students rarely have trouble landing positions they pursue, whether in academia, government or the non-profit and private sectors.

Santana Quintero amid the beautifully painted walls of Queen Nefertari’s tomb.

Another outcome of the international work is local capacity building. In fact, that’s the focus of some of the projects, such as the work on Bahrain’s Pearl Road. The route is being documented and mapped to assist conservation and tourism efforts, and locals are being trained in the latest digital documentation techniques.

International experience and capacity building are also central to the work in Bagan, the ancient capital of the kingdom that eventually became Myanmar. More than 2,000 Buddhist temples and pagodas — most built between the 11th and 13th centuries — are still standing.

CIMS cotutelle PhD candidate, Davide Mezzino, spent time on the ground in Bagan recently doing risk-assessment documentation and updating an existing heritage inventory with the support of the California-based CyArk Foundation and in collaboration with UNESCO, Myanmar’s Department of Archeology and Museums and Yangon Technological University.

Mezzino’s research will assist the development of a monitoring application to assess changes in the condition of the temples and pagodas in addition to detecting which structures are most susceptible to damage and testing the effectiveness of various conservation techniques.

“It’s not only the structures we’re helping preserve,” says Mezzino. “It’s the intangible value of the culture.”

Heritage conservation conference coming to Carleton

Santana Quintero will be bringing some of his international contacts to Carleton’s campus at the end of August when the university hosts “Digital Workflows for Heritage Conservation,” the biennial symposium of the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) and International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing (ISPRS) scientific committee on heritage documentation (CIPA).

It’s the first time a CIPA gathering is being held in North America, and only the fourth time since ICOMOS was established in the mid-1960s that the symposium is being held outside Europe.

Heritage Engineering master’s student Alex Federman hard at work in the entrance to Queen Nefertari’s tomb.

Santana Quintero, who is CIPA’s vice-president and past president, expects about 300 delegates to attend. The keynote speakers include Richard O’Connor, chief of heritage documentation programs at the U.S. National Park Service, and Chance Coughenour, program manager at Google Arts & Culture, who co-ordinates cultural heritage preservation efforts on a global scale.

“Hosting this important conference,” says Santana Quintero, “will hopefully help us develop more critical mass for a heritage conservation mindset in North America.”

Monday, July 10, 2017 in Graduate Students, History, Research

Share: Twitter, Facebook