By Tyrone Burke

In a swampy, subtropical forest, in the murky depths of time, a tiny creature crawled onto the land. It was no more than a few centimetres long, and it wasn’t the first animal to seek sustenance on solid ground — but this moment forever impacted life on Earth.

This creature was different from the amphibians that came before it. It was an amniote. Its eggs had a membrane surrounding the fetus they held. This protected its offspring, and meant it could reproduce on land. Its descendants and cousins ventured ever further from shore. They grew larger and dominated the land. They evolved wings and soared in the sky. Today, many of the animals we know best are amniotes: reptiles, birds, mammals – even ourselves.

Carleton University’s Hillary Maddin is looking for evidence of that first proto-reptile in the fossilized tree stumps slowly eroding out of the cliffs that line Nova Scotia’s Bay of Fundy coast. Located near present-day Amherst, N.S., the Joggins Fossil Cliffs helped 19th century geologists identify and understand the Carboniferous period – about 300 to 360 million years ago. It is during the Carboniferous that the first species we would recognize as modern animals appeared.

The Importance of the Joggins Fossil Cliffs

The Joggins Fossil Cliffs yielded the oldest known reptile fossil – Hylonomus lyelli, which was discovered by eminent 19th century geologists Charles Lyell and William Dawson. Maddin hopes that six stumps loaned to her lab by the Nova Scotia Museum will help her and her students identify specimens that are even older. And they’re not only looking for reptiles. The research could help shed light on amphibians. It remains unclear how groups like frogs and salamanders are related and how they evolved.

“Molecular data predicts that the split between the modern groups happened sometime in the Carboniferous period,” said Maddin, an associate professor of vertebrate palaeontology and evolutionary developmental biology.

“Nova Scotia is one of the only places in the world that has rocks of the age that capture animals from the approximate time the modern groups split from one another.”

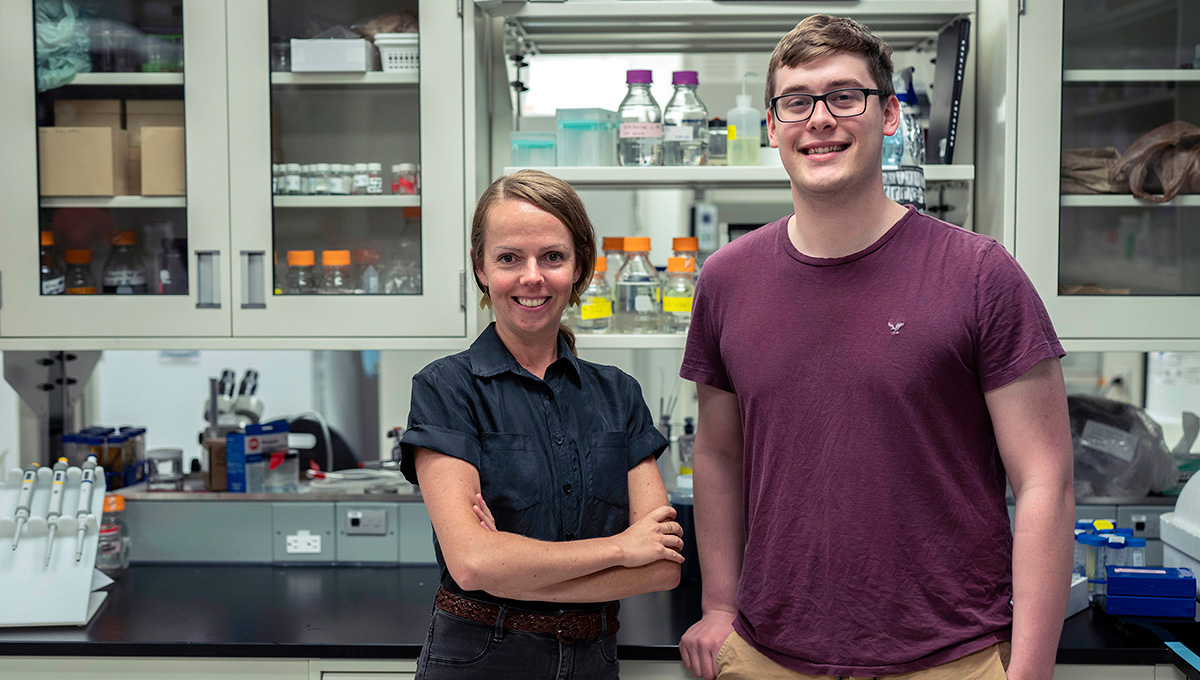

A Collaborative Effort

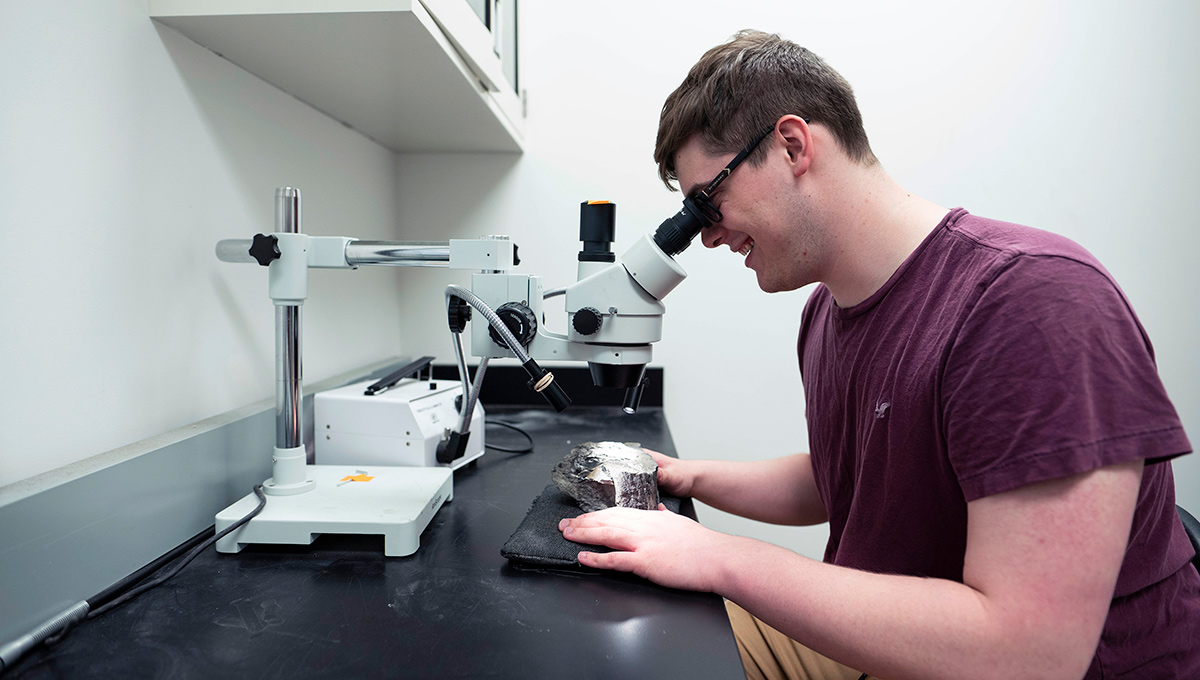

In Maddin’s lab in the Herzberg Building, first-year paleontology student Logan Micucci is staring intently at a fragment of a prehistoric stump, picking gently at the fossil stump with a tool that resembles a dentist’s plaque scraper.

“That’s a bit of bone there,” said Micucci, who worked in the lab on a Dean’s Summer Research Internship.

“This was all hidden before, and I uncovered that bit that looks like a little hockey stick.”

The stumps are large, and it’s a collaborative effort between Carleton, Saint Mary’s University and the Nova Scotia Museum to reveal and identify the tiny animals preserved inside.

“There is definitely a preferential bias to preserve the smaller things,” said Maddin.

“We think small animals were hiding or living in these stumps, or they were small enough to get washed into them. We don’t really know how they got in there.”

A few larger animals have been found at Joggins, but for Maddin, it is discovery of the ancient relatives of modern amphibians and amniotes that lived during the late Carboniferous that makes the time period so intriguing.

“Before that time, it is really hard to identify animals as anything living today,” she said.

“This the first bit of animal life that we would really recognize. Everything before looks kind of blobby, like a lumbering, unspecialized creature. You can see that it is a creature, but it’s not really one thing or another yet.

“Once we get into this part of the Carboniferous, we see the first representatives of things that might give rise to true, modern reptiles, as well as mammals. If we look at animals alive today — this is where all of their earliest records are coming from. These are the first insights we have into how those groups came to be, and basically took over the globe.”

Friday, September 27, 2019 in Earth Sciences, Faculty of Science, Research

Share: Twitter, Facebook