By Jonathan Malloy

The anti-Asian shootings at three massage parlours in Atlanta, Ga., in March 2021 have complex religious elements. Eight people, including six Asian women, were killed in the attacks. The alleged shooter emerged from an evangelical “purity culture” that teaches a narrow view of sexuality, often with racial undertones.

Purity culture has both specific and broad meanings. It directly refers to a 1990s wave of practices of “extreme abstinence,” mainly directed at women. But it also incorporates decades of broader evangelical teachings restricting sexuality to within heterosexual marriage.

While some argue that purity culture only refers to the narrow 1990s practices that even many evangelicals now distance themselves from, there is no clear distinction and the underlying ideas are the same. According to Bradley Onishi, an American professor of religious studies, women are taught to “hate their bodies” and men to “hate their minds.” This is the mindset that led the accused Atlanta perpetrator to claim he was plagued by a “sexual addiction,” because he felt unable to manage his sexual thoughts and urges through purity culture’s hardline approach of denial and self-loathing.

Purity culture also taps into xenophobic and racist views of non-white cultures as exotic and sexually licentious. Canadian ex-evangelical Jenna Tenn-Yuk writes that “women of colour … do not get to be seen as pure.” Asian American ex-evangelicals like Angie Hong, Flora Tang and Onishi have also explored the connections between purity culture and the fetishization of Asian women in the wake of the Atlanta shootings.

(AP Photo/Mike Stewart)

Repressing ‘impure’ sex

Purity culture in its broadest sense is fundamental to evangelical thinking. But it is not simply anti-sex. While it represses sex outside of heterosexual marriage, it valorizes and celebrates married heterosexuality. This has been called the “sexual prosperity gospel.”

Purity culture operates primarily through self-perpetuating systems of peer accountability. Evangelicalism is a decentralized movement, and evangelical legitimacy largely rests on acceptance by other evangelicals. So purity culture is a complex worldview, embedded in broader tenets and social structures, for both men and women.

Evangelical Christianity has always liked to think of itself as adapting to cultural and technological change. But shifts in gender and sexual attitudes over recent decades have left evangelicals uncomfortably out of step with the rest of North American society.

There is some evidence of evolving evangelical attitudes on sexuality, especially LGBTQ equality. But actual change within the evangelical world is difficult. Purity culture is an interlocking system of regulating all sexuality. It resists incremental evolution.

When evangelical leaders and adherents move away from purity culture tenets, they lose their standing and access within the evangelical world. Many end up walking away entirely.

Canadian evangelism

In Canada, purity culture is mostly invisible in mainstream society, much like evangelicals themselves. But it remains fundamental to evangelical thinking.

My research has shown that, unlike the United States, most Canadian evangelicals have given up fighting for cultural dominance. Instead, they are fighting to preserve their own private spaces. This is most evident in the struggle to maintain anti-LGBTQ exclusions as part of the broader system regulating all sexuality.

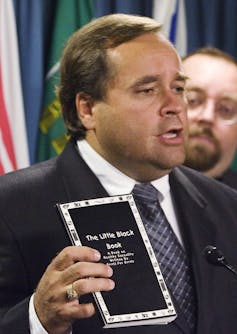

While Canada does have aggressive American-style evangelical activists like Charles McVety, they are less dominant in evangelical circles than in the United States.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Fred Chartrand

The majority of Canadian evangelicals are more subtle. Some are clearly aware that homophobic teachings are driving people away. Many downplay the issue as much as possible.

But they can’t easily moderate their actual positions on LGBTQ rights and other sexuality issues. To do so would bring down the entire house of cards of purity culture.

Instead, Canadian evangelicals have reframed their views in a more positive way as “pro-women.” This is based on purity culture’s framing of women as vulnerable and needing protection, again often with underlying racial tones.

One example is the strong evangelical support for the Stephen Harper government’s so-called “Nordic model” of prostitution law. The model targets buyers of sex over sex workers themselves. This follows purity culture’s focus on “protecting” women. But the law still stigmatizes sex work and sex workers, who are largely women and often racialized.

Canadian evangelicals and other anti-abortion activists have also narrowed their efforts to focus on campaigning against sex-selective abortion of girls. This uses the practice of sex-selective abortion in other parts of the world as a basis for campaigning against abortion in Canada. This allows for a pro-woman framing that implicitly upholds the ideals of purity culture.

Purity culture and especially its anti-LGBTQ aspects may not be as entrenched as they seem. Some evangelicals are well aware they have painted themselves into a corner of intolerance and are out of step with Canadian society.

But reform within the evangelical world is difficult. Instead, evangelicals, especially in Canada, are reframing the tenets of purity culture to appear more palatable, without letting go of its underlying tones and beliefs.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Carleton University is a member of this unique digital journalism platform that launched in June 2017 to boost visibility of Canada’s academic faculty and researchers. Interested in writing a piece? Please contact Steven Reid or sign up to become an author.

All photos provided by The Conversation from various sources.

![]()

Tuesday, April 20, 2021 in The Conversation

Share: Twitter, Facebook