By Dan Rubinstein

Photos by Neville Agnew, Robert Jensen, Sara Lardinois and Lori Wong, courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Trust

Since it was discovered by archaeologist Howard Carter in 1922, the tomb of King Tutankhamen has been one of the most significant — and most visited — cultural heritage sites in the world.

But thousands of tourists who descend on Egypt’s Valley of the Kings each year, and the humidity, carbon dioxide and dust they inadvertently bring into Tutankhamen’s 3,300-year-old tomb, has a destructive impact on the elaborate wall paintings inside the pharaoh’s burial chamber.

Ten years ago, the Los Angeles-based Getty Conservation Institute (GCI), in collaboration with Egypt’s Ministry of Antiquities, began a major research, conservation and infrastructure improvement project to safeguard the site, improve the experience for visitors and create a sustainable plan for continued management of the tomb. In 2017, the Carleton Immersive Media Studio (CIMS) was engaged by the GCI to document King Tut’s tomb and its decorated surfaces.

Photo provided by CIMS

The conservation project was completed late last year, and the photography that has emerged highlights one of the contributions of CIMS. The restored wall paintings vividly come to life with the help of a new lighting setup that was designed with data provided by a team led by Prof. Mario Santana Quintero.

“For us, it was an outstanding opportunity to be involved in such an important project,” says Santana Quintero, an Architectural Conservation and Sustainability scholar on faculty with CIMS. “The Getty Conservation Institute is one of the world’s leading-edge institutions.

“The experience inside King Tut’s tomb is incredible,” continues Santana Quintero, who first visited the site as a tourist travelling around the region when he was in his mid-20s.

“But one shortcoming was always the lighting. Now you can really appreciate and admire the colours. This is a great example of what you can do to protect a site and show it off to visitors.”

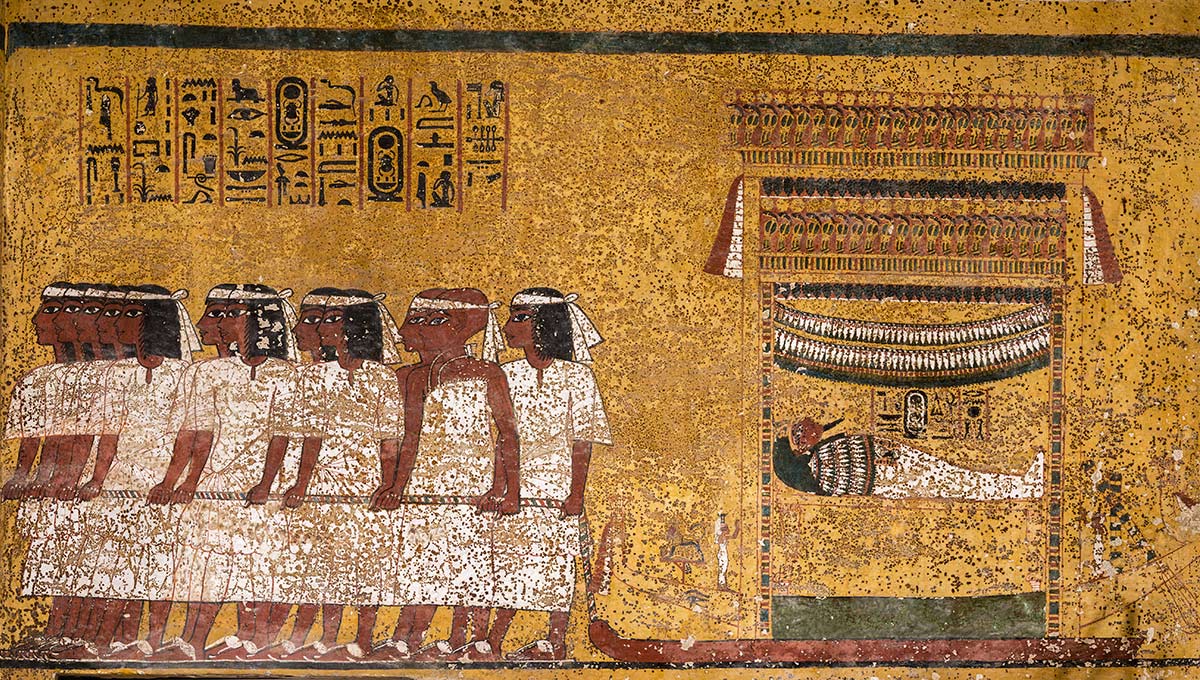

Although many treasures from King Tut’s tomb are now housed at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, the tomb “still houses a handful of original objects, including the mummy of Tutankhamen himself (on display in an oxygen-free case), the quartzite sarcophagus with its granite lid on the floor beside it, the gilded wooden outermost coffin, and the wall paintings of the burial chamber that depict Tut’s life and death,” says CGI.

“Conservation and preservation (are) important for the future,” Zahi Hawass, the former minister of State for Antiquities in Egypt who initiated the project with the GCI, said in a press release, “and for this heritage and this great civilization to live forever.”

Documenting and Preserving Some of the World’s Most Important Heritage Sites

From the subterranean mystique of King Tut’s tomb and the sunbaked 1,000-year-old temples of Bagan, Myanmar, to the ancient homes on Bahrain’s Pearl Road and the earthquake-damaged earthen buildings in Katmandu, Santana Quintero and his students painstakingly work to help document and preserve some of the world’s most important heritage sites.

In March 2017, Santana Quintero, Heritage Engineering master’s student Alex Federman and CIMS instructor Christian Ouimet spent nearly two weeks laser scanning and taking detailed photographs inside both Tutankhamen’s tomb and the nearby tomb of Queen Nefertari.

The orthorectified (or geometrically-corrected) images and photogrammetry data they captured in Tutankhamen’s burial chamber was used to generate digital maps and meshed surface models that represented with extreme accuracy the textured three-dimensional relief of the wall paintings.

“The data we collected was of very high quality,” says Santana Quintero, “and captures the current as-found state of the tomb after restoration. It can be used for a variety of purposes, such as structural analysis of the site.”

This information was given to the GCI, who shared it with the project’s lighting consultant, Studio Three Twenty One.

Prof. Mario Santana Quintero

“Mario and the team were very helpful in helping us get the modelling data into a format that the lighting designer could import into his programs,” says CGI project specialist Sara Lardinois, explaining that, ultimately, two-foot-long LED lighting fixtures in a continuous aluminum enclosure with adjustable feet were placed on the ground. The lighting system was set back from the wall to minimize grazing the wall texture, which can interfere with the legibility of the paintings.

“All of these models and floor plans allowed the lighting designer to do analysis and generate simulations showing what different lighting solutions could look like,” says Lardinois.

“This the new lighting helps people really see the wall paintings. If you can’t read the iconography, it hinders your experience in the tomb.”

Beyond the lighting and restoration work on the paintings themselves, other improvements in the tomb include a new ventilation system to filter out dust and humidity, new interpretive signage, and a new viewing platform in the antechamber that allows visitors to see the paintings while preventing anybody from accidentally (or intentionally) touching the walls.

“All of this had to be designed and installed in a way that didn’t impact the archaeology,” says Lardinois, noting that a detailed floor plan and cross-section model of the tomb produced by CIMS helped with this process.

“Every surface is historically important.”

For Lardinois, Santana Quintero and others involved in the project, it’s hard not to focus on the technical details and the challenges of working in a confined space. (The tomb is 122 square metres, with a 58-square-metre covered entry area.)

“But then you step back at look at the 3,000-year-old wall paintings, or the sarcophagus in the middle of the room, and I’m never not amazed,” she says. “And that happens every time.

“It’s been a remarkable experience for us to have an opportunity to work in the tomb with all of our partners and consultants, including Carleton,” adds Lardinois. “It’s been a hugely collaborative effort.”

Training Egyptian Conservators in the tomb of King Tutankhamen

In addition to the data capture and documentation, Santana Quintero and his CIMS colleagues also helped train a pair of Egyptian conservators who were working on the Tutankhamen project.

They did intensive one-on-one instruction on documentation techniques, equipment usage and software workflow. This training, in fact, occupied the majority of their time in the tomb.

“They have a lack of equipment, but not a lack of willingness,” says Santana Quintero.

“I was very impressed by the Egyptian trainees.”

Now that the project in King Tut’s tomb is finished, Santana Quintero — who is currently on sabbatical and spending three months with the GCI in Los Angeles doing research on ethical principles for the application of digital workflows in heritage conservation — has turned his attention to the sprawling Paphos archaeological site on Cyrpus.

The GCI and Cyprian Department of Antiquities (DoA) have been collaborating at the Roman-era site since the mid-1980s, beginning with a mosaic conservation project, and are now preparing a conservation and management master plan for the Nea Paphos UNESCO World Heritage Site.

To provide the groundwork for that plan, CIMS was commissioned to produce a digital record of the as-found conditions of the site. The project is intended to help improve visitor understanding and experience, and to provide the GCI and DoA with the capacity to use the heritage information system to guide conservation objectives.

All of this hands-on work is an excellent example of experiential learning, says Santana Quintero, for the Carleton students who participate.

“We don’t do these projects to make money,” he says.

“We do them for conservation purposes, and to create opportunities for undergraduate and graduate students, so they can develop the skills and experience that the non-profit and private sectors require, and so they can help us advance the field.”

Tuesday, April 23, 2019 in Faculty of Engineering and Design

Share: Twitter, Facebook