By Joseph Mathieu

Photos by Joseph Mathieu and Pinegrove Productions

As Chaffey’s Lock fills with 1.3 million litres of water, Carleton Biology Prof. Nigel Waltho gives his class a quick pep talk.

“The focus for these remaining morning dives, especially if we lose opportunities due to poor weather, is fundamental skill training in the colder, deeper waters,” he says.

An hour and a half southwest of Ottawa, the 37th Rideau Canal lock raises their pontoon boat the 11 feet separating Opinicon Lake from Indian Lake. The boat is stocked with scuba and scientific research gear, safety gear, and binders full of diving data and checklists.

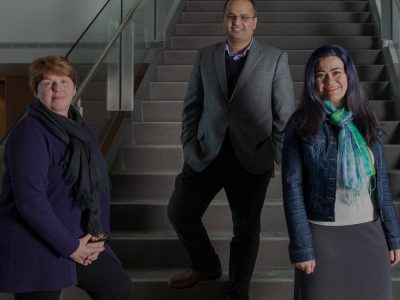

Lobsang Wangkhang, Carleton Biology Prof. Nigel Waltho and Frances Parry having a bite before another dive.

Six students huddle around Waltho, who is sitting on a lunch cooler as water pours in around the bobbing classroom. The students are both bleary-eyed and excited on this rainy late summer morning. The group has caught the lock’s first lift of the day, just after 9 a.m.

“I encourage all of you folks, after you first pass through the thermocline, to take a bearing on the shot-line and practice for a few minutes with your mask off.”

The thermocline is a layer of water 15 to 20 feet below the surface. In the sunny Caribbean sea, this layer is much deeper and the water is warm through all diving depths. In an Ontario lake, however, the water beneath the thermocline is a frigid 4 C all summer.

Waltho reviews the goals of day 12 of this Canadian Scientific Research Diver field course before the lock station’s doors open. He makes sure his students are well fed, hydrated and rested. If there is more to worry about here compared to his other, more traditional classroom environments, Waltho doesn’t let it show. In fact, he seems to relish it.

“Such a terrible office to have to work in,” he says with a wink.

Natasha Leclerc and Lucy Martin-Johnson

The Ontario Universities Program in Field Biology (OUPFB) offers 30 field courses, including Waltho’s. Enrolled students come from any of the 15 participating universities as long as they meet course prerequisites.

Four OUPFB courses are offered by Carleton biology professors – Chris Elvidge’s on fish ecology and fisheries, Grégory Bulté’s on turtles, and Waltho’s other course on the ecology of coral reefs. Three take place at the Queen’s University Biological Station (QUBS) on Opinicon Lake; the coral reefs course is in the Bahamas.

Before Waltho met his scientific research diving students in person, the six of them—all certified scuba divers—had two months to study and write weekly chapter quizzes based on the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association’s diving manual. On their first day at QUBS, the six divers had to prove their in-water competencies: treading water for 20 minutes, swimming and snorkelling, and towing a fully-dressed scuba diver 100 metres.

Then began a solid two weeks of dive training and scientific dive training each morning and afternoon, followed by three- to four-hour lectures each night.

Prof. Waltho in the water with several students.

And the pace never let up.

Frances Parry studies marine and freshwater biology at Guelph University. She hopes to use her certification in a master’s program or a job assisting researchers to collect data.

Lobsang Wangkhang, an environmental toxicology student at Queen’s University, wants to take her scientific diving skills to the Arctic one day. Lucy Martin-Johnson, studying ecological restoration at Trent University, thinks scuba diving could give her discipline a chance to better understand and examine aquatic ecosystems.

“We learned techniques to be better, safer divers,” says Parry, already a certified diving instructor.

“In those two weeks, my diving abilities grew substantially.”

Scientific Dive Training

A solid approach to scientific research is just as important as diving skills to Waltho’s field course.

“Before conducting underwater research, you must first have a clearly developed experimental research design,” he says.

“That includes a proposed framework for statistical analysis, otherwise your field efforts may be inadequate or excessive. Either (can) lead to wasted time, effort and resources.”

Frances Parry

To illustrate this point, Waltho teaches his students how to determine the required sample count to obtain proper statistical precisions. From these sample counts, and by calculating each of their air consumption rates, students learn how to determine the number of scuba tanks required to complete proposed field work—and thus what kind of budget they’d need. This connecting-the-dots approach helps them grasp how to plan and conduct research diving.

Which means there’s a lot for Waltho to teach, from theory to practice, in two weeks. Once the field course concludes, students have two months to develop and submit a complete research proposal and dive plan on an aquatic or marine topic of their choice.

“This course could enable Carleton to lead academic research dive training for all of Ontario,” says Waltho, who joined Carleton in 2005.

Safety Always First

Before every descent, divers pair with buddies and check each other’s gear. On their twelfth day, Parry partners with Floyd Pinto, a software engineering student from Guelph, Ont., who is minoring in geographic information systems and environmental analysis.

“Do you want to do this with your eyes closed?” he asks, as each inspects the other’s weights, buoyancy compensator devices, zippers and breathing apparatuses. They’ve done it blindfolded before. Waltho makes buddy checks routine before the start of each dive to ensure familiarity, not just with their own equipment, but with their partner’s.

“The hardest part for me was diving deep, where it was cold and dark,” says Wangkhang.

“But I overcame it by becoming familiar with my gear and contingency planning with my buddy prior to the dive.”

Floyd Pinto

After returning to the surface, a diver places her closed fist on her head to signal that all is well. During this first iteration of the Canadian Scientific Research Diver field course, this was the surfacing sign 100 per cent of the time.

It’s not uncommon for divers to emerge from the depths covered in aquatic plants called macrophytes, resembling fish-creatures from dank lagoons. And while there are no lake monsters—besides the invasive zebra mussels whose tiny shells can cut the skin—there are still several underwater threats.

Nitrogen narcosis, or “the martini effect,” starts to occur near100-foot depths. More water pressure forces increases nitrogen concentrations circulating in the blood. This can lead to inebriation and a lack of judgment—a serious issue when 30 metres under water.

“It affects different people at different depths on different dives,” says Waltho.

“The challenge is to be vigilant and that’s where training comes in. We don’t dive deep from the get-go, but approach 100 feet after many dives of gradually increasing depths.”

There’s also several kinds of decompression problems caused by swimming too quickly to the surface. Dive planning, situational awareness and control of ascent speeds — three foundational elements to Waltho’s course—are key to mitigating risk factors.

A Deep Dive

Just as Waltho takes his students deeper into the course materials—from boatmanship and navigation to underwater photography and ecological statistics—the six divers go deeper into the lakes.

“The diving really pushed my comfort levels, but all to make me a better diver and prepare for emergency situations,” says Isabelle Ouimette, a University of Ottawa graduate in environmental science.

Student researcher Isabelle Ouimette prepares for a dive.

Natasha Leclerc, an earth sciences PhD candidate at the University of Toronto, came out of the course feeling more comfortable and confident as a diver. She had signed up to learn to manage her thesis project collecting coralline red algae specimens near Cambridge Bay and Gjoa Haven, Nunavut.

“The field course was quite an education,” she says.

On their twelfth day, with five “DIVER BELOW” buoys set up and a blue and white alpha flag flying from the pontoon (“stay clear, divers below”), all systems are go. The excited students suit up, some of them preparing for their first-ever 80-foot dive.

Then two men in an outboard motorboat whiz by, pulling a girl on a kneeboard. The lakes are, after all, popular cottaging destinations. They aren’t too close but they aren’t exactly keeping clear. One of the men says loudly to the other: “They’re diving!”

“Heck yeah we are,” says Leclerc.

Monday, October 21, 2019 in Biology, Faculty of Science, Research

Share: Twitter, Facebook