By Joel Lexchin, Barbara Mintzes, Lisa Bero, Marc-Andre Gagnon, and Quinn Grundy

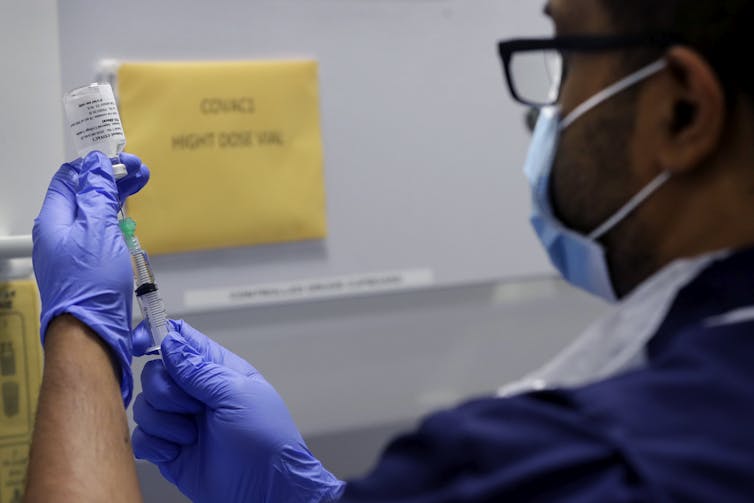

Hopefully there will soon be a vaccine for COVID-19. In fact, there may be more than one. Once there is, Canada will probably spend hundreds of millions of dollars, if not billions, on the vaccine or vaccines.

In August, the federal government signed deals with two United States vaccines producers, Novavax and Johnson & Johnson, to purchase tens of millions of doses of their vaccines should they prove to be successful. In September, further deals were concluded with Pfizer, Moderna, GlaxoSmithKline/Sanofi and AstraZeneca.

Public acceptance of any vaccine will depend on how confident the public is that the best decisions have been made about which vaccines to ultimately use. If it looks like decisions are based on advice from people with conflicts of interest with vaccine makers then confidence and uptake of the vaccine could collapse.

We all want the government to proactively make decisions so that once a vaccine is approved, it can be quickly delivered to Canadians. But how are those decisions being made? Back in June, the National Research Council set up an 18-member COVID-19 Vaccine Task Force charged with, among other things, prioritizing vaccine projects seeking support for activities in Canada, and identifying opportunities to enhance business connectivity globally to secure access to commercially sponsored vaccines.

Task force links with industry

The task force members are advising the government about decisions that will affect the health of the entire Canadian population. At first, we knew their names and current positions, but nothing about any relationships with vaccine manufacturers.

In fact, the government decided that it was acceptable for task force members to have clear conflicts of interest. A government statement said that in order to be sure that the leading experts were on the task force, there was a “deliberate decision … to include individuals who may have a real or perceived … conflict of interest with respect to one or more proposals to be evaluated by the … task force.”

They all had to disclose conflicts, but those disclosures were kept secret and were only available to the secretariat assigned to support the task force and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada. No provisions were made for representation of groups disproportionately affected by COVID-19 on the task force, including Indigenous and Black people, the elderly, women or people with disabilities.

At its meetings, the Task Force was asked to consider whether to recommend purchasing vaccines from Johnson & Johnson, Moderna, Novavax and Sanofi. One or more of the Task Force members declared a conflict with all of these companies but none of the conflicts were considered direct and therefore the members were not required to step away. Subsequent to the Task Force meeting, the Canadian government signed contracts with all of these companies.

Dr. Joanna Langley of Dalhousie University, co-chair of the task force, was asked in early September about whether there should be more transparency. Her reply was that government ministers receiving advice could see what was disclosed:

“… and whether or not the ministers decide to make that public, really, it’s not for me to say … I would have to review all the kinds of information that everyone has given to say, is it fair to make that public when people are doing this? … It’s volunteer service.”

Oversight and transparency

The voluntary nature of the COVID-19 Vaccine Task Force was also why the ethics commissioner, Mario Dion, did not have the authority to oversee conflicts of interest of members. The task force’s lack of transparency has led one member to resign. Gary Kobinger, who headed the Winnipeg team that developed a successful Ebola vaccine, pleaded for more transparency.

Probably because of all of the negative publicity, the federal government has now released the COVID-19 Vaccine Task Force’s conflict of interest declarations at five meetings between June 26 and Sept. 3. Reading these disclosures is revealing both for what they do and don’t say.

When the task force discussed the vaccine being developed jointly by Sanofi Pasteur and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), Dr. Langley declared that Dalhousie University, where she works, has collaborated with Sanofi Pasteur and GSK in the past on clinical trials; she has collaborated on other research projects with Sanofi scientists (unpaid); and served as a consultant to Sanofi on influenza vaccines in 2018, with payment for this work going to Dalhousie’s department of pediatrics. According to the minutes of the meeting “as there are not direct, material linkages, it was not considered a conflict and recusal was not deemed necessary.”

The task force also decided that Mark Lievonen, the other co-chair, who was the CEO of Sanofi Canada for 17 years (until 2016), still owns shares in Sanofi, is associated with a consulting company working with drug companies and the director of two other drug companies, was not considered to have a direct, material conflict. However, “in an abundance of caution M. Lievonen recused himself from deliberations and recommendations.”

Not just transparency, but independence

Other countries have handled this type of situation much better. Back in April, the Australian government funded the National COVID-19 Clinical Evidence Taskforce to provide rapid, evidence-based and continually updated advice on Australia’s health response to the COVID-19 pandemic. It ran its proposed conflict of interest standards by an independent panel (four of the authors of this piece formed the expert panel), made modifications based on its input and published the final policy. Since then we have been consulted regularly about individuals’ decision-making roles and whether the requirements of the policy are being met.

Dr. Fiona Godlee, editor in chief of the BMJ, was asked by Global News about conflict of interest in vaccine research and oversight. In response, she said:

“I think it’s a basic issue of trust that people want to see what’s gone into decisions or recommendations, and that includes both the person’s expertise and the potential or real influences on any recommendations or decisions they may make … It’s become a standard thing.”

Ultimately, while necessary, transparency is also insufficient. Independence is needed: task force chairs and most members should not have conflicts. With Canadian lives on the line, trust in decisions about vaccines is going to be crucial. Instead, that trust has already been jeopardized.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Carleton University is a member of this unique digital journalism platform that launched in June 2017 to boost visibility of Canada’s academic faculty and researchers. Interested in writing a piece? Please contact Steven Reid or sign up to become an author.

All photos provided by The Conversation from various sources.

![]()

Thursday, October 8, 2020 in The Conversation

Share: Twitter, Facebook