By Joseph Mathieu

Photos by Gregory Abraszko

A celebration of the resilience of black Canadians was held for hundreds of Carleton University students, colleagues, activists and allies at Dominion-Chalmers United Church on Feb. 13, 2019.

Organized by Carleton University’s Black History Month Committee (CUBHMC), Still Standing: 400 Years of Black Excellence in Canada brought together student and faculty leaders from the Black Students Alliance (BSA), the Afro-Caribbean Mentorship Program (ACMP), and Carleton’s School of Social Work.

“It is imperative that we give individuals of all races an opportunity to learn about a part of Canadian history that we may have limited awareness of,” said Prof. Allison Everett of the School of Social Work and CUBHMC founder. “We organized this event as a means to begin to address this gap.”

“Tonight, we carry on the legacy of Mathieu Da Costa and others through song, poetry, dance and critical dialogue,” said Everett, referring to the man believed to be the first free black person to visit these shores in the early 1600s.

Sisters from Sigma Beta Phi

Six sisters from the Carleton and uOttawa chapter of Sigma Beta Phi, the first predominantly black and bilingual sorority in Canada, performed a step dance to kick-start the evening. They also freestyled to the beat of “Woke,” performed by Jah’kota, an Ottawa-based hip hop artist and entrepreneur with Jamaican and Nakota First Nation roots. The crowd chanted the chorus back, clapping along, and every attendee stood for “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing,” as Ryan Oféi’s voice filled the cavernous Woodside Hall with the uplifting black national anthem.

City of Ottawa Poet Laureate, Jamaal Jackson Rogers, known in literary circles as JustJamaal thePoet and a member of Missing LinX, presented a poem that paid homage to the legacy of black Canadians. He prefaced the poem with his experience as a culture-shocked nine-year-old returning to Canada from Guyana, South America.

“This event is not meant to celebrate black excellence during one event or one month, but to encourage equity and equality for black people in Canada today,” said CUBHMC member and ACMP founder Warren Clarke.

The CUBHMC is comprised of individuals from the BSA, the ACMP, the School of Social Work, the Department of Equity Services, the Department of Sociology and Anthropology, and the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences.

What it Means to be Black in Canada

Clarke, who emceed the evening alongside Everett and BSA Co-President Eileen Adams, moderated a group discussion on stage. Seven panelists shared their thoughts on what it means to be black in Canada, where they find inspiration, and what their communities need to thrive.

“In Canada, things are so much better here so it doesn’t allow (us) to have conversations about how things are hard for us,” said Robert Alsberry, outreach co-ordinator for Max Ottawa.

Ottawa CTV news anchor Stefan Keyes, who graduated from Carleton’s School of Journalism and Communication in 2009, was born and raised in Ottawa. He said that from a young age his citizenship was constantly called into question by authority figures.

“In Canada, blackness is suspect,” said Social Work Prof. Melissa Redmond. “Always being considered suspect means I have to always give answers to certain questions: ‘Where are you from? What are you doing?’ It’s not about the truth of my experience. It’s about having to predict what the questioner wants me to say.”

“I think that we can do better in regards to cultural compromise and conformity, especially in the workplace,” said Keyes. “I feel as though unless you speak the cultural language there is some hesitation there. Look at my resume, my skillset and my character.”

“We need to start better exploring black identities and personalities,” said Zakiyyah Kukoyi, director of arts and cultural projects with Stolen From Africa.

“Black people are constantly told that we are living in the past by talking about racism, that we have a chip on our shoulders because of oppression, or we use the race card, that we can’t get over it,” said Yusra Osman, a counsellor at Carleton’s Health and Counselling Services. “We often respond to this through amazing celebrations of our history, like here tonight.

“We’ve been here for 400 years. Let’s also think about what the next 400 years of blackness in Canada are going to be.”

Sharing the Diverse Insight and Experience of Black Canadians

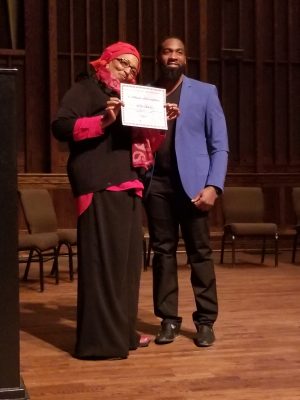

As women and men of diverse black backgrounds shared their insight and experiences with the audience, Adams and Clarke awarded certificates of recognition to community members of note. Recipients were chosen by committee as those working hard to contribute to the Afro-Caribbean and black communities.

“It was important for us to identify those who were doing it from the heart and doing it for positive contributions to their communities,” said Clarke.

Nimo Bokore and Warren Clarke

Recipients included David Oladejo, outgoing president of the Carleton University Students’ Association (CUSA), School of Social Work Prof. Nimo Bokore, incoming CUSA president Lily Akagbosu, and University of Toronto lecturer L.A. Wade.

Wade also presented her developing research into the contradictory nature of black female conformity stemming from the work of American behavioural psychologist Brené Brown.

“We often try to [belong] by fitting in and by seeking approval, which are not only hollow substitutes to belonging, but even barriers to it,” she said. “Belonging doesn’t require us to change who we are. It requires us to be who we are.”

As a keynote speaker, Ottawa-raised Christo Bilukidi gave a play by play of his path from Russell Heights community housing to becoming a defensive end for NFL teams like the Oakland Raiders and Baltimore Ravens.

After playing for Atlanta’s Georgia State University and being drafted to play professionally in 2012, Bilukidi decided he ultimately wanted something else out of life. In 2017, he decided to return to his roots, began a career in real estate and became an Ottawa Community Housing ambassador.

In 1926, American historian and scholar Carter Woodson declared “black history week” to be the second week of February, overlapping the birthdays of former U.S. president Abraham Lincoln and abolitionist Frederick Douglass. The week expanded into a month-long celebration in 1970 and was more widely celebrated across the United States by 1976.

The celebration was first observed by the Ontario Black History Society in 1978. However, Black History Month in Canada in February wasn’t officially declared until 1995 in the House of Commons and 2008 in the Senate.

In the event’s final moments, a young woman asked how she could make her high school more receptive to Black History Month, and Keyes recounted how, in Grade 11, he had spelled out its importance to his principal.

His high school administrators weren’t planning to host an event because there weren’t many black students at the school, he said. Keyes had to explain how Black History Month wasn’t just for him, it was for everyone because it was a human history.

“It is a shared history,” he said. “It’s about understanding that this is not how you treat people . . . and then also celebrating the resilience of humanity and how far those people have come.”