By Joseph Mathieu

Modern political activism is far too complex to be explained in black and white, but it happens all the time. Democratic or dictatorial, rational or racist, armchair activism or real-world demonstration — which is it?

Reality is far more nuanced, which is something that Carleton University Communications Prof. Merlyna Lim, Canada Research Chair in Digital Media and Global Network Society, has always understood.

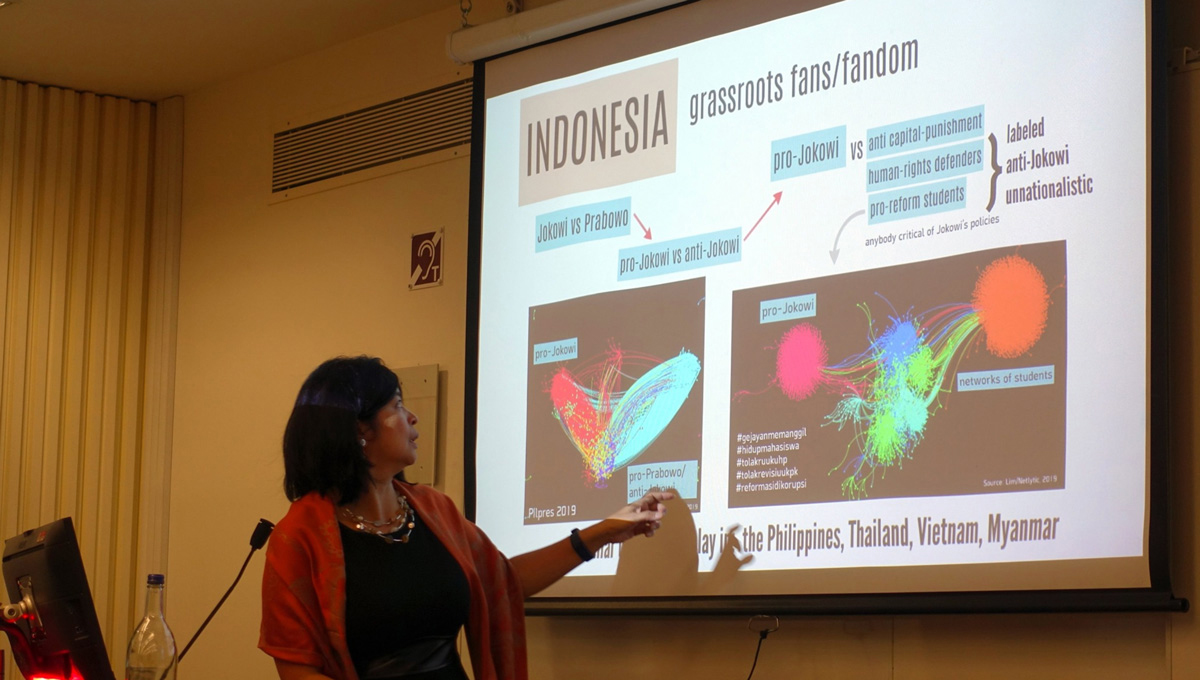

Lim’s study of both online and offline activism (as well as the combination of the two) requires many different approaches to describe their complexity. She conducts online and real-world observations, in-depth interviews, data research and literature reviews to understand how movements mobilize, where people gather and how messages spread in the cyber and civic realms.

Prof. Merlyna Lim

With the renewal of her Canada Research Chair in 2019, Lim has expanded the scope of her research. She will study the social and political rhythms of various countries where social media narratives have spread quickly. Algorithms play a big part in spreading certain ideologies online, but this has to be weighed with cultural context.

“People bring their own bias to everything,” says Lim. “What we are experiencing is not just because of social media — it’s amplified by it and still shaped and reshaped by users.”

Lim has conducted research on social movements in many places, including Southeast Asia, Hong Kong, Tunisia, Egypt and Syria. More recently, she studied misinformation in Canada during the 2019 federal election and the movements in Malaysia surrounding electoral reform.

With the onset of COVID-19, her field work — talking to people about their lives, social circles and customs — will continue remotely.

“I’ll continue working on doing the online part of my research and interviewing from afar,” says Lim. “Of course, with the pandemic, there are many emerging social movements and collective actions that traverse both online and offline realms.”

Lim still plans to travel to Southeast Asia, Singapore and urban areas such as Kuala Lumpur, Manila and Jakarta in 2021. Her recent research on hate speech and social media is not the first time she has studied mass communication and social change in her home country of Indonesia.

Lessons from the Streets

As an architectural engineering student, Lim witnessed the student movement to remove the authoritarian former president Suharto. What culminated in nation-wide protests in May 1998 — and the president’s resignation — began in Jakarta, Bandung and other cities where student activists organized online and in physical spaces.

“I was not the most active, I was mostly observing,” says Lim. “But I was on the street with thousands of other students.”

Lim focused her PhD thesis on these and other movements in Indonesia. She explored the complexity of the situation, dismissing the simple description of “Internet revolution,” and outlined how taxis, mosques and food stalls played important roles in the movement.

“Digital activism doesn’t bloom from a vacuum,” she says. “It springs from the context of technology and socio-political problems.”

Lim will also continue to research and work with her ALiGN (Alternative Global Network) media lab, which does public outreach to help progressive groups communicate complex issues. The lab offers thought-provoking podcasts, videos and comics, as well as workshops to support communities that wish to better mobilize their causes.

In March, ALiGN hosted a media training and writing workshop for refugees in Kenya’s Kakuma Camp and published a story by Zamzam Abdikader, one of the workshop’s attendees, who wrote about life in the camp during the pandemic.

“My research is very objective, but morally I’m not neutral,” says Lim, “I’m for marginalized communities. I seek to empower the voices of refugees and activists for democracy.”

Alongside Prof. James Milner in the Department of Political Science, Lim will also help international refugees communicate their needs and issues by telling their own stories. They wish to share their knowledge with small groups — especially progressive youth movements — that are fighting for equality.

“I want them to see that there is hope,” says Lim. “We can do better. How do we build a movement if authoritarians keep winning? There are more of us — we just have to be connected.”

Monday, July 6, 2020 in Communications and Media Studies

Share: Twitter, Facebook