Understanding tea drink’s microbial mix is the key to consistency

By Tyrone Burke

Photos by Justin Tang

Its fiercest advocates claim that drinking kombucha can help address a dizzying array of health problems, from diabetes to a weak libido, but Ottawa’s Buchipop isn’t brewing the fermented, fizzy tea-based beverage as a folk remedy — they want to bring it to the soda-swilling masses.

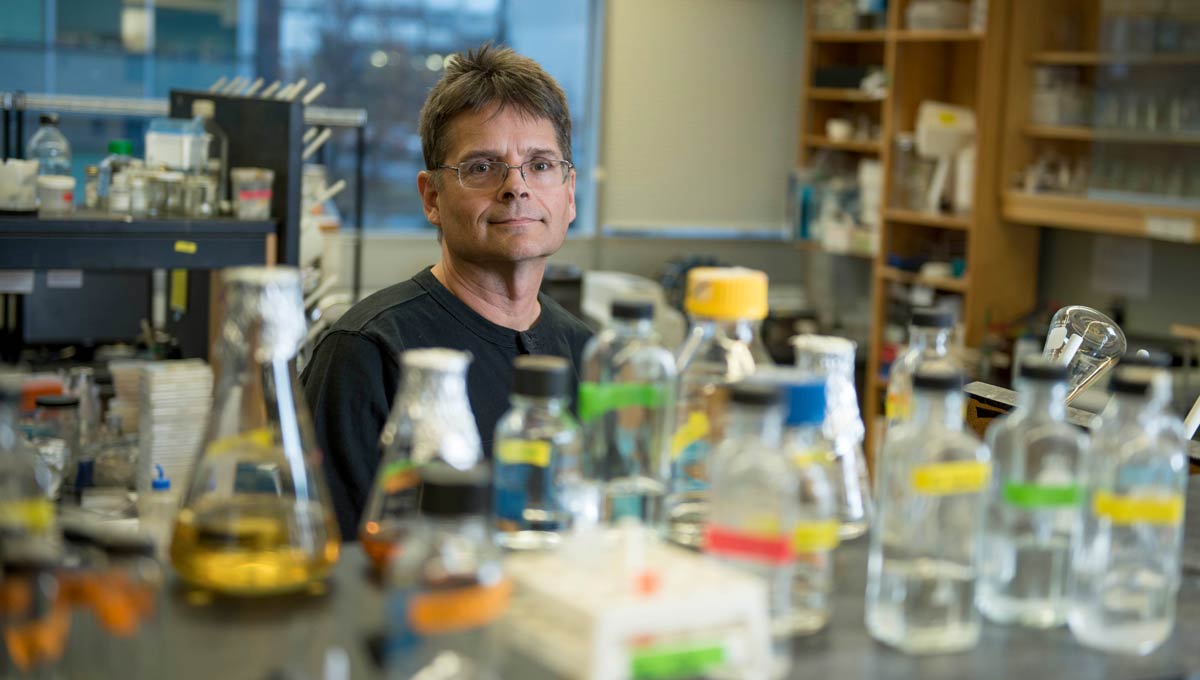

Carleton University microbiologist Myron Smith

“Our focus isn’t really on the health side,” says Patricia Larkin, who started the company in early 2016 after five years as a chef at one of the city’s top bistros.

“That’s part of who drinks kombucha, but we want soda drinkers to love it too. I see us as a lifestyle brand. An alternative to soda, with health benefits.”

Kombucha traces its lineage back two millennia to ancient Manchuria, but despite this pedigree, little is known about exactly what it is. That’s because of kombucha’s microbial complexity.

Drinks such as wine and beer ferment a single yeast, but kombucha relies on a symbiotic community of bacteria and yeast in a complex fermentation process that produces an alcohol content of less than one perfect, similar to many other foods and beverages.

To complicate matters, it uses an open system that allows external microbes to become part of that community, contributing unique local flavours.

“You don’t try to keep it clean of environmentally introduced microbes,” says Carleton microbiologist Myron Smith, a genetics expert whose lab is working with Buchipop on a research project. “Different regions have different microbes. So there won’t be the same species, or the same strain, but there will be something that lives well in a region that does the same job.”

Buchipop taps into a growing market

With global sales forecast to climb 25 percent every year until 2020, kombucha is a growing segment in a crowded beverage industry. In a food culture increasingly driven by the local, the drink’s regional specificity is a marketing asset but a challenge to growth.

To expand, Buchipop needs to produce consistent kombucha on a large scale, and a dynamic production process with unknown microbial components presents a hurdle to consistency.

Smith’s lab in the Nesbitt Biology Building is sequencing the DNA in Buchipop’s symbiotic community of bacteria and yeast using a high throughput sequencer. By examining the metagenome — the genome of the entire community — the lab can identify microbial DNA to determine the proportion of a particular species in the mix, and identify exactly which components are present at each stage of fermentation.

“You can imagine a pie chart that says 10 percent of the cells are from this bacterium, and 20 percent from this yeast,” Smith says.

“Then a week later, you can see how that community has changed.”

Achieving consistency with Carleton’s expertise

Understanding what is happening as kombucha ferments could enable Buchipop to better manage flavours in the end product, and achieve the consistency the growing company needs to expand beyond the roughly 40 local restaurants currently selling its products.

“I’m very proud to be an Ottawa company,” says Larkin, “but I’d like to be an Ottawa export. For Buchipop, this is just the beginning.”

Wednesday, March 29, 2017 in Entrepreneurship, Faculty of Science, Research

Share: Twitter, Facebook