By Dan Rubinstein

Photos by Brenna Mackay & Laura Hunter

In a brand-new lab at Carleton University, biomedical engineering PhD student Hossein Sadat Hosseini attaches several loonie-sized wireless sensors to the arms and legs of a patient who is recovering from a stroke.

A three-foot-tall rehabilitation robot made by Carleton spin-off company GaitTronics rolls toward the patient, encircles his waist with a cushioned belt and mirrors his movements as he slowly stands, turns and begins to walk.

Rehabilitation technology by Carleton University spin-off company GaitTronics.

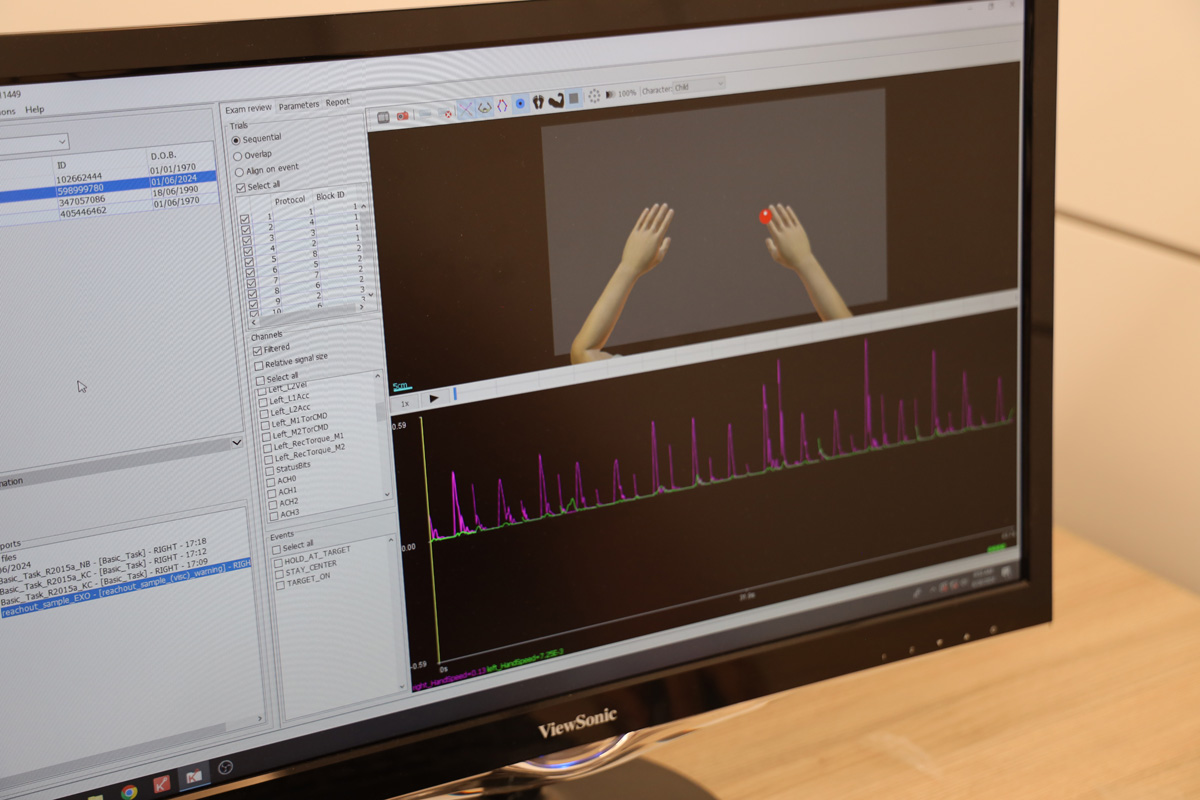

The sensors record electromyography data — the electrical activity of muscles — that Hosseini will feed into an AI model. This will help the robot learn about the patient’s motion patterns, evaluate his progress and train the machine to better support his recovery.

“This is really rewarding research because we’re helping people who are dealing with strokes, cerebral palsy and other impairments,” says Hosseini.

“We’re using powerful tools to improve the quality of life for people with so many different kinds of challenges.”

Introducing the Abilities Living Laboratory

This type of scenario will soon be the norm inside Carleton’s Abilities Living Laboratory, a malleable, multidisciplinary space in the university’s ARISE (Advanced Research and Innovation in Smart Environments) Building.

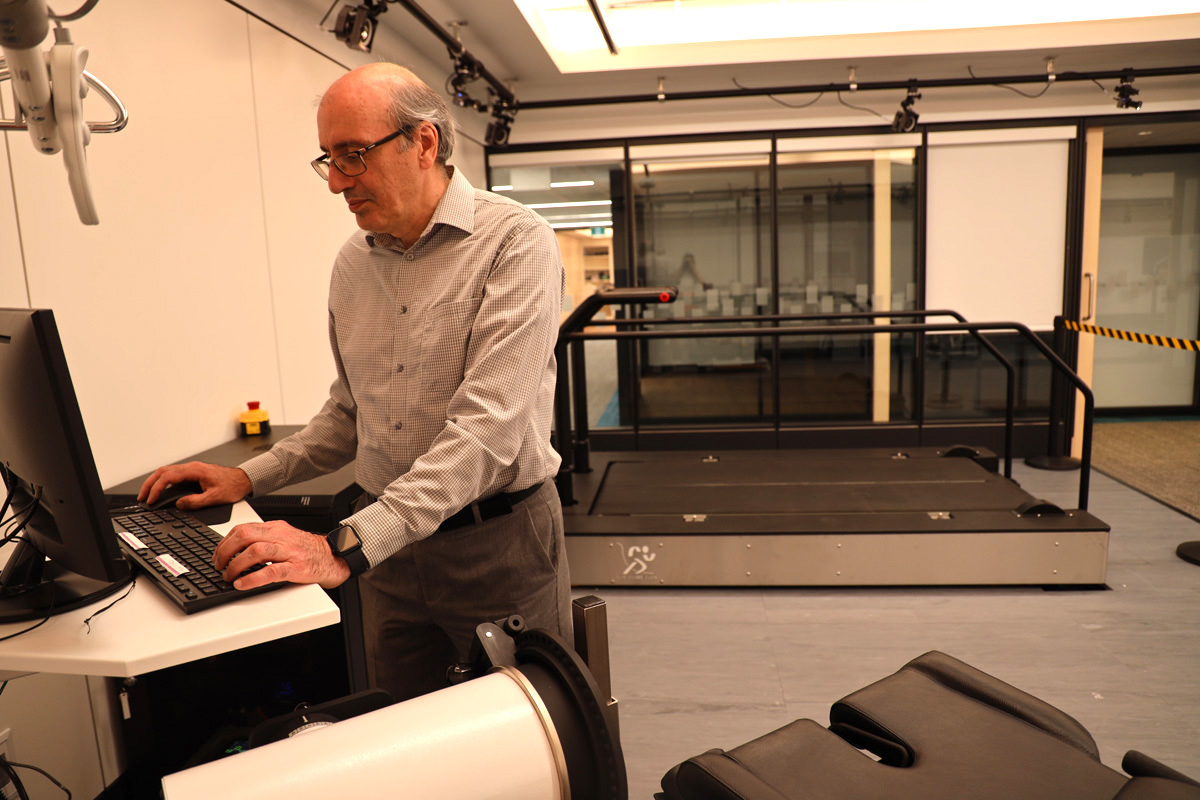

Hosseini and his supervisor, Mojtaba Ahmadi from the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, are among a diverse group of Carleton faculty, students and community collaborators who will be using the new lab to design, prototype and test solutions that not only enhance personal mobility for people with disabilities but also support full inclusion in public and cultural life.

Carleton biomedical engineering PhD student Hossein Sadat Hosseini and his supervisor Prof. Mojtaba Ahmadi

“A lot of our labs are packed with equipment and aren’t suitable for people to participate in experiments,” says Ahmadi.

“This facility will allow us to develop new technologies and then bring in patients, health-care professionals and other researchers to help us refine our work. The big picture is that we’re helping people lead fulfilling lives.”

Cross-Pollinating Research Ideas

Before visitors even enter the Abilities Living Laboratory, its unique functionality is apparent. The shared kitchen in the hallway — where scientists can bounce ideas off one another over lunch — is a wheelchair-friendly space for research into areas such as accessible meal prep, including new gadgets.

That kitchen looks into a glassed-in Food Design Lab, where Carleton biochemist Farah Hosseinian, from the Food Science program, and Chantal Trudel, director of the Industrial Design program, will work on innovative projects.

Industrial Design program director Chantal Trudel

Some of these will involve using a 3D printer to study personalized food manufacturing — combining layers of proteins, grains, fruits, vegetables and sugars, for instance — for people with dysphagia (difficulty swallowing). It could also be used to tailor foods that appeal to people who experience loss of appetite or food aversions, including seniors and cancer patients.

“We’ll have the ability to experiment,” says Hosseinian, “and create nutritious foods with different visual, textural, structural and olfactory attributes.”

Trudel, whose background is in health-care design, will also be working in another space inside the main facility, a “blank slate” with magnetic whiteboard walls and fully adjustable lighting control. It can be used to simulate a range of environments, such as a hospital room, and look at issues like light and sleep difficulties for patients.

Carleton University biochemist Farah Hosseinian

Later this summer, Trudel and a grad student will begin installing a prototype infectious disease treatment transfer screen in this lab — essentially, a flexible, airtight, see-through barrier, with a glove box, allowing clinicians to observe and treat a patient without being exposed to pathogens. This screen will be developed in close collaboration with WHO-Téchne and is part of INITIATE2, a five-year initiative which brings together emergency response actors and research and academic institutions to develop solutions and training in support of readiness and response capabilities in health emergencies.

“In design, we need spaces to build iterative mock-ups, cycle people though and learn what’s working and what’s not,” says Trudel.

“Now we have somewhere on campus to do these types of experiments.”

High-Tech Human Performance Studies

The biggest space in the Abilities Living Laboratory is the Human Performance Lab. A collection of high-tech equipment — force plates embedded in the floor, an instrumented treadmill and staircase, an advanced motion capture system — will allow researchers to conduct gait analysis and study how subjects balance and move.

Abilities Living Laboratory director Adrian Chan

“Carleton’s work on accessibility has been evolving over a number of years,” says Adrian Chan, director of the overarching facility and one of the researchers who’ll be using the Human Performance Lab.

“Now we have an environment where we can move solutions from the benchtop to everyday use.

“This is much more than a utilitarian approach to accessibility. It’s about full participation in leisure, culture and community.”

Prof. Jesse Stewart

Music professor Jesse Stewart’s We Are All Musicians Lab is part of this mindset — a space devoted to making music as inclusive as possible.

“This involves testing existing assistive and adaptive musical instruments and co-developing new ones,” Stewart says, “to ensure that everyone has opportunities to make music, regardless of musical training or ability.”

“It’s been a long journey to get here,” adds Chan.

“Our equipment is just being installed, and I’m excited about how people are going to collaborate and use this space.”

Monday, July 15, 2024 in Accessibility, Innovation, Research

Share: Twitter, Facebook