By Tyrone Burke

Photos by Chris Roussakis

The World Wide Web unleashed a torrent of information unlike anything that preceded it.

In 1989, British physicist Sir Tim Berners-Lee proposed the idea as a way to help researchers at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) connect and share their findings. Thirty years later, his invention has connected more than 4.4 billion people around the world with a vast, ever-expanding archive of information.

The web ushered in an era of technological change that transformed nearly every aspect of our lives. It reinvented how we learn, choose a restaurant and find a date.

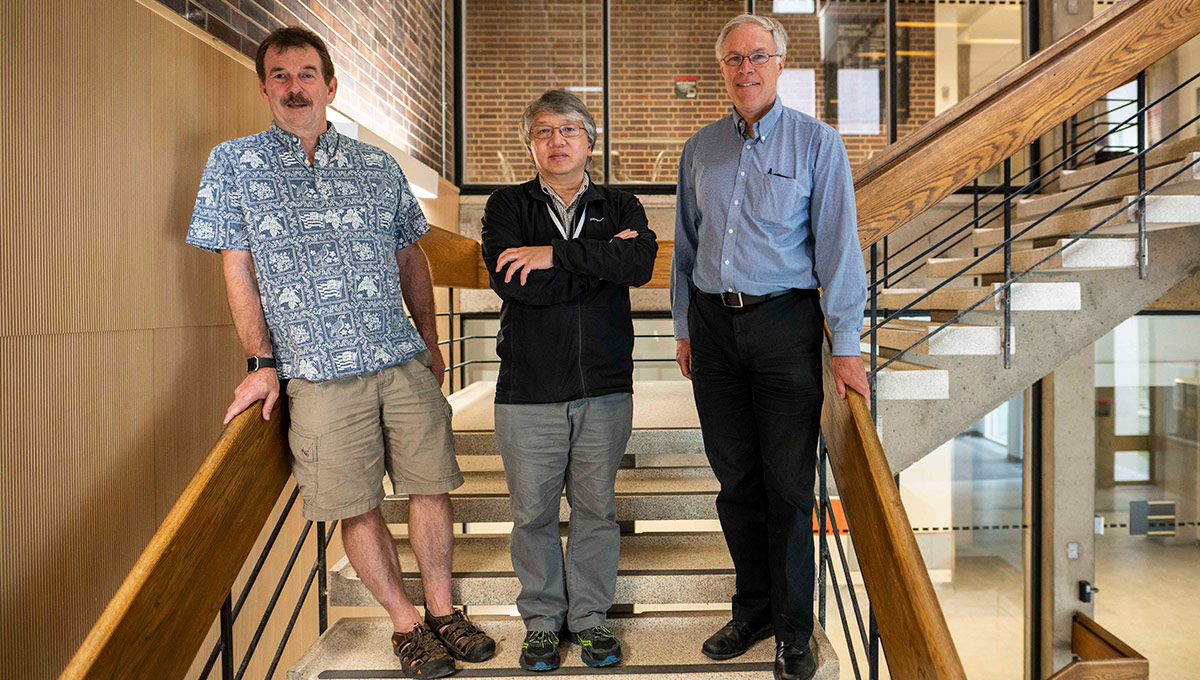

Geology Prof. Tim Patterson

Those changes didn’t happen overnight. In the early days of the web at Carleton University, with the technology still in its infancy, it had a long way to go.

Geology Prof. Tim Patterson was an early adopter. In 1996, he began giving students the option of contributing to an online museum instead of writing a term paper. At the time, the idea was considered innovative enough to merit an article in the New York Times.

When Patterson dreamed up the Hooper Virtual Natural History Museum — which he named after former Carleton Earth Sciences Prof. Ken Hooper — the entire World Wide Web consisted of about 23,000 websites. There was no YouTube, no Facebook; even the New York Times hadn’t launched its website yet.

Two and a half decades later, there are nearly two billion websites, including an archived version of the Hooper Museum. It’s a simple site by today’s standards, but at the time it was on the leading edge. The museum was even part of the Canadian Pavilion at the Internet World’s Fair in 1996, which Carleton led and hosted.

“Back then, there were none of the programs people use today,” Patterson says.

“Dreamweaver and Squarespace have made it very easy to build a website with templates. For the Hooper Museum, students actually had to learn HTML and code.”

With so much effort put into development, web-based term projects typically didn’t have as much detail as regular term papers.

“But our aim was to make it accessible for people in grade school or high school or the general public,” says Patterson. “Students got excited because the web was still new then. They’d say, ‘Wow, there’s someone who will see this who is living in Australia.’”

The Early Days of the Internet at Carleton

In the early days of the web, the idea that someone halfway around the world could see your work was a powerful one. Connectivity was accelerating, but the ability to communicate instantly with people anywhere on Earth was still so novel that Carleton’s early web users were not even phased by ploddingly slow connection speeds.

In 1989, Carleton accessed the Internet, allowing researchers to better collaborate with their colleagues around the world. That connection transferred data at just 56 kilobytes per second. It was the highest speed available at the time but is far slower than even the slowest home connections today.

John Stewart

“You’d think that it would have been too slow, but it was actually revolutionary compared to what we had before,” says John Stewart, a computer systems and network administrator in the School of Mathematics and Statistics.

“Previously, Carleton’s email used a ‘store and forward’-type service. If you were sending a message to someone in Australia, it would first go from our mainframe computer through a data line to a mainframe computer at the University of Ottawa, and then it might sit in a queue there waiting to get through the next connection to a computer at Queen’s, and then it might sit in the queue there before being transmitted to the University of Toronto and so on.”

It could take hours — even half a day — for an email message to get to Australia.

“But when it became a direct connection, I can remember faculty members calling me to tell me they’d sent a message to a colleague in Australia and got a reply 10 minutes later,” says Stewart. “It really made the email service vastly more useful.”

Connecting to the Global Community

In the earliest days of the web at Carleton, users were mostly scientists, mathematicians and engineers, but in 1992, Carleton played a role in taking the Internet beyond the university’s walls.

Founded at Carleton, the National Capital Freenet was Ottawa’s first Internet service provider. A small bank of modems on the Carleton campus provided dial-up access to the public; 10,000 people signed up in the first year alone.

Commercial Internet would not be available for another four years and, for many Ottawa residents, the National Capital Freenet provided their first exposure to the Internet. The technology provided the basis for Carleton’s first student portal, as well as for a web-based system for undergraduate physics tutorials and testing developed by Professor Emeritus Peter Watson, then chair of the Department of Physics. This learning management system came long before the CU Learn of today.

The Web Goes Viral

But for the web to truly go viral, it took more than just access.

Open source software made it easier to create content and applications. Web browsers made it easier to navigate the web. And eventually, cell phones allowed us to carry it with us in our pockets.

Wade Hong

Those who built the university’s web capabilities could see the technology’s promise early on, even the pieces of the puzzle that were not yet in place.

“The building blocks were there,” says Wade Hong, an information technology officer for the Faculty of Science.

“And you had an opportunity to use them. Today, a lot of these building blocks are built for you. The Internet and web applications are already built, and they’re increasingly easy to use. Back then, people were trying to build the tools. It was a totally different experience, and it was a heady and exciting time to witness and participate in.”

Friday, July 5, 2019 in Computer Science, Information Technology, Technology

Share: Twitter, Facebook