By David J. Hornsby

The #FeesMustFall protests of 2015 and 2016 have made an indelible mark on higher education in South Africa. The protests left no university untouched. And they elicited significant emotions: for, against or a mixture of the two.

Most could agree with the sentiments that underpinned the protests. Students wanted more equitable access to higher education. They called for free education. But there was significant disagreement and concern around their methods of protest, tactics and outcomes.

Student leaders from the time will rightly claim victory. Tuition increases were frozen for the 2016 academic year. Support workers who had been outsourced were given permanent employment at some institutions. The government agreed to create a fee-free university environment for those below a determined household income threshold.

Those who opposed the protests will argue that the sacrifices made to secure these gains came at too great a cost. Students and staff were traumatised. Infrastructure was destroyed. Books and artworks were burned. The reallocation of financial resources had real consequences in the broader society: government expenditure on the social wage declined in nominal terms, making it more difficult for South Africa’s most vulnerable citizens to survive.

These positions persist and have not been reconciled. More than ever, South African universities need a new social contract that charts a way forward and begins to heal divisions.

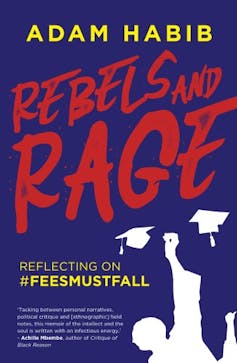

Two Vice Chancellors – one who has completed his term, the other still serving– have written books on the issue. The first, As by Fire, the end of the South African university, was written by Professor Jonathan Jansen. He ran the university of the Free State during the protests. More recently, the vice chancellor of the University of the Witwatersrand (known as Wits), Professor Adam Habib published Rebels and Rage.

My analysis of Habib’s book is that it is a participant-observer account but does little to contribute ideas that might be used to develop such a contract or to move South African higher education forward. This is a pity given that this was meant to be a central premise of his leadership at Wits.

Division and contestation

Habib proffers a set of insights and commentary on the politics and political economy of what took place at Wits and across the sector. He situates his analysis in discussing moments and offering personal reflections. It is an insider view of the protests.

Quite rightly, he argues that a lot was at stake during #FeesMustFall, in particular the integrity of the whole higher education sector. He weaves this narrative throughout a series of chapters that seek to unpack particular moments, events and the individuals involved in this. But often, these end up being derisive of others; questioning tactics, political motivations, aspirations and ideology.

Some of this is understandable, especially when considering some of the deception or miscalculations that took place or when questioning the intellectual basis – such as quoting Frantz Fanon and Steve Biko – for engaging in violence.

But the issues and moments raised remain divisive, contested and are certainly not settled. At times the book feels like an endeavour to settle scores and to use the authority and privilege assigned through being the Vice-Chancellor to set the narrative. He frequently uses hyperbolic, dismissive language.

This creates a real conundrum for Habib when he needs to execute his role as the final point of decision-making. For academics and students derided in the book, can they reasonably expect fair treatment by their Vice-Chancellor on matters pertaining to career and studies?

Disclosure

In the spirit of full disclosure, I was present and involved in the protests in 2015 and 2016. I am mentioned in the book, but am not counted among the major role-players and come in for no particular praise nor scorn.

When the protests began, I was an academic and was among the leaders of the Academic Staff Association of Wits University.

Our main role throughout was to be present and try – where possible – to diffuse conflict between students, staff, police and private security and to build understanding. Some of us were tear gassed, shot with rubber bullets, had stones thrown at us or were pushed around by various parties. Sometimes we were effective, and other times we were not. The scar on the back of my head can attest to this.

I witnessed many of the stories and moments Habib describes. He offers insights and reflections that feel familiar and make logical connections, and his account of some events is accurate.

But gaps also emerge among these recollections.

What’s missing

Habib contends that this is a personal reflection on the #FeesMustFall movement. Yet he makes assumptions about other people’s intent. Here I think not just of students, but also of some academic staff whom he seems to set up as proverbial boogeymen. To Habib, he was right, and anyone who disagreed with him, was wrong. This is an overly simplistic approach to a complex set of moments and leads to unfair characterisations.

I also found Habib’s lack of self-reflection and ownership over decisions and how some events unfolded striking. The reader gets some glimpses, such as his regret over berating a student for requesting security assistance for student residences. But this is a unique moment and little consideration is given to actions and decisions taken at the senior management level.

For example, was it helpful to issue written warnings to protesters in 2015 threatening arrest for blocking entrance gates? Did it diffuse the situation to use an apartheid era trespassing law? Finally, how does he reconcile his beliefs with the fact that the protesters were ultimately successful in achieving their ends and what does this mean for social movements in South Africa?

No one emerged from #FeesMustFall a hero or a villain. Everyone made mistakes. Everyone miscalculated. Everyone misunderstood elements of the moment. Instead of pointing fingers and casting blame, what is needed is consideration and thought into how Wits and other South African universities are going to move forward.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Carleton University is a member of this unique digital journalism platform that launched in June 2017 to boost visibility of Canada’s academic faculty and researchers. Interested in writing a piece? Please contact Steven Reid or sign up to become an author.

All photos provided by The Conversation from various sources.

![]()

Thursday, May 2, 2019 in The Conversation

Share: Twitter, Facebook