Lead image by libre de droit / iStock

By Dan Rubinstein

Photos by Terence Ho

When presented with images of an inkblot-like rounded shape and a spiky shape and the made-up words “bouba” and “kiki,” the vast majority of people are likely to associate bouba with the curvy shape and kiki with the jagged one.

The “bouba-kiki effect” holds for both English and non-English speaking study respondents, and for everybody from university students and older adults to very young children. In some experiments, 98 per cent of people reached the same conclusion, though the average is just below 90 per cent.

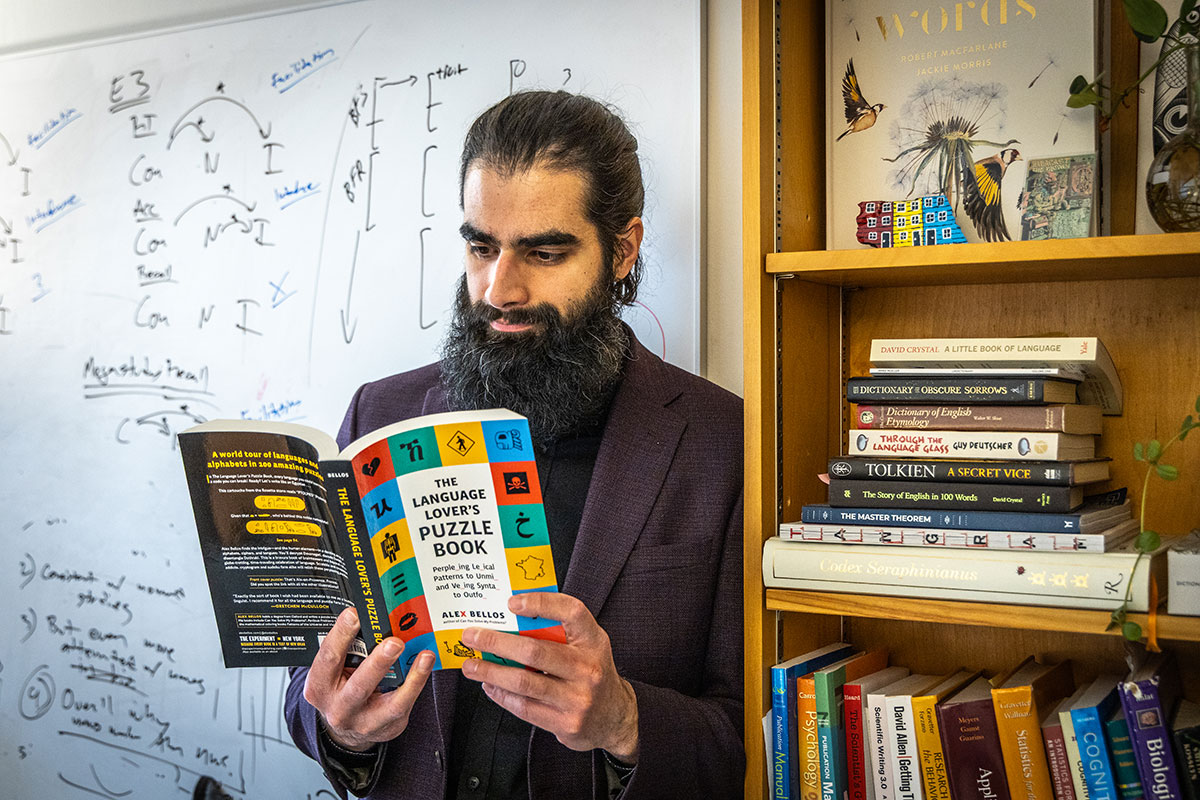

Carleton University psychology researcher David Sidhu first read about this phenomenon in an undergraduate class.

Carleton University psychology researcher David Sidhu

“It was like finding a secret layer of meaning that you don’t really notice until someone points it out,” he recalls.

“Then you start seeing it everywhere. That really appealed to me, these hidden codes in language. It must have really gotten lodged into my brain.”

A few years later, as a cognitive psychology grad student, Sidhu dove deep into sound symbolism. This area of research, which is one of the foci of his Cognition, Language, Sound Symbolism, Iconicity (CLaSSI) Lab at Carleton, explores why people intuit links between language sounds and characteristics such as shape, size and colour as well as things like tastes, emotions, personality traits and more.

Iconicity, meanwhile, refers to words that sound like their meanings, including onomatopoetic examples — “squeak” or “crash” — and more subtle ones such as “bumbling” or “balloon.”

The first words that infants tend to learn are iconic words that imitate the sounds of things in the world, says Sidhu, so there seems to be a link between sound and language learning. Some researchers have made the claim that our ancestors began communicating verbally by imitating sounds before we made the leap to vocabulary.

“I’ve always been interested in how we make connections between fundamentally different kinds of things,” says Sidhu. “For example, thinking about abstract paintings, how somebody can look at a shape or a colour and think, ‘that’s justice,’ or ‘that’s love.’ I’ve also always been interested in language and how we can use sounds to project what we’re thinking into another person’s mind, almost like telepathy.

“Sound symbolism is kind of the connection of these two things. It looks at how cross-modal associations affect language, and how the sound of a word impacts its meaning.”

Although this research may seem theoretical, it has myriad real-world implications. More insights into language functionality could help us parse language learning, the evolution of communication and the black box of human cognition. It has applications in fields as diverse as neuroscience and marketing. Ultimately, it could help us understand ourselves and one another a little better.

Sound Symbolism and Time

In a paper he co-authored last year with Carleton psychology colleague Johanna Peetz, Sidhu looked at the relationship between sound symbolism and time.

They determined, in a study using nearly 8,000 made-up pseudowords, that people tend to associate sounds with “high front vowels and voiced fricatives/affricatives” with the future and sounds with “voiced stops” with the past.

Findings like this could help companies devising names for products, Peetz and Sidhu write, considering that “attributes of modernity are particularly attractive to consumers.” On the flip side, past-associated sounds could be more effective when naming nostalgic products.

This type of research is relatively straightforward to conduct. Generally, people sit at a computer, look at a rapid succession of words on the screen and have to respond immediately. A lot of data can be collected fairly quickly.

In addition to time, Sidhu is also exploring whether we find certain sounds calming or exciting and our perceptions of names and personality. “For softer names, like Liam, people expect them to be very kind, very emotional,” he says. “And with harsher names, like Kirk, people expect them to be more outgoing.”

Sidhu is finishing up a paper looking at whether we think individuals might be a better fit for a specific job based on their names alone.

Applications to Daily Life

All these years after his undergraduate studies, Sidhu is still not entirely sure what’s behind bouba-kiki effect.

The theory he’s most drawn to suggests that we attach meanings to words based on the sensations we get as we pronounce them. The “buh” of “bouba,” for instance, has a softer internal articulatory sensation than the “ka” of “kiki.”

Other theories suggest that “bouba” mimics the sounds that round things make in the world, while “kiki” — a more “aggressive” word — reflects sounds made by spiky things.

“It’s funny,” says Sidhu, thinking about the bouba-kiki effect, “even though it’s the question I started off with I still don’t have the answer.

“Language is a part of almost everything we do,” he adds, “so understanding how we process and use language has applications to almost every aspect of daily life.”

First wide image by monsitj / iStock

Monday, April 7, 2025 in Psychology, Research

Share: Twitter, Facebook