By Dan Rubinstein

Mangroves are very impressive plants.

A type of woody tree or shrub that grows along tropical or subtropical coastlines, they have evolved to thrive in salty, low-oxygen terrain.

Thanks to this resilience, mangroves help protect shorelines from waves and storm surges, reducing the risk of flooding. Their dense root networks bind soil in place, mitigating the impact of erosion and rising seas. They also improve water quality through filtration, support biodiversity by providing habitat for animals and other plants and sequester significantly more carbon than mature tropical forests.

Planting mangrove seeds to boost this natural defence system is a labour-intensive process, but Carleton University student Stefan Teodorescu has come up with a creative, high-tech and very impressive solution.

Carleton University aerospace engineering student Stefan Teodorescu (left) and Oscar Barbieri

The 19-year-old, first-year aerospace engineering major and his high school classmate Oscar Barbieri created the “Mangrover,” an autonomous seed planting robot that came in first place at a national robotics completion in Montreal last spring.

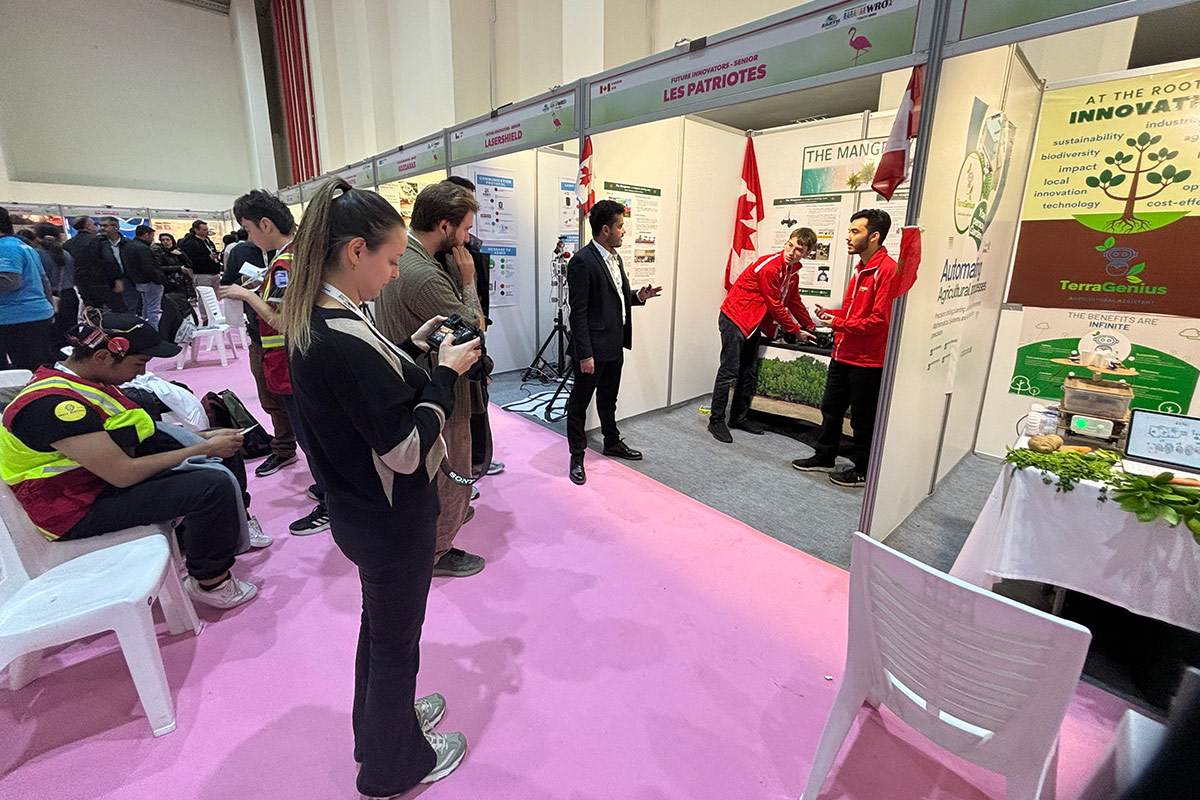

That victory propelled the duo to the World Robotics Olympiad in Turkey in November, where they finished at the top of the silver category and 12th overall.

“Mangroves are unique because of the environments they grow in and the benefits they provide,” says Teodorescu, who was familiar with the plants from family trips to the Caribbean but learned more about their importance from an aunt who had travelled to the Pacific Islands.

“I did additional research and started to think about ways to fight climate change that aren’t super obvious, such as through robotics. Technology is a double-edge sword. It can cause problems, but it’s also a powerful tool.”

Systematic Thinking Leads to Solutions

Teodorescu’s father worked for a 3D printer company and Stefan was exposed to technology at a young age. Before reaching double digits, he was building circuits on breadboards — bases for designing and experimenting with electronic circuits.

“I enjoyed the systematic thinking,” Teodorescu recalls.

“There’s a problem and you want a solution, so you have to come up with a logical plan to get there.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, he developed an interest in ham radio — “radio circuits are more math intensive!” — and a high school tech class led to robotics.

“I really liked the fact that you had to solve electrical, mechanical and software problems,” Teodorescu says. “It was kind of the ultimate combination. You have to apply systemic thinking but it’s so dynamic.”

Although he had only previously built Lego Mindstorm robots, he started working with one of his teachers on a slow-moving line-following robot: a 40-kilogram metal body, repurposed from an old pay-to-print vending machine, driven by a hacked Roomba.

Another teacher told Teodorescu about World Robotics Olympiad, which prompted him to pair up with Barbieri and begin the project that ultimately led to the Mangrover.

At first, their plan was to make a garbage collecting robot. Then he talked to his aunt and a new idea took root.

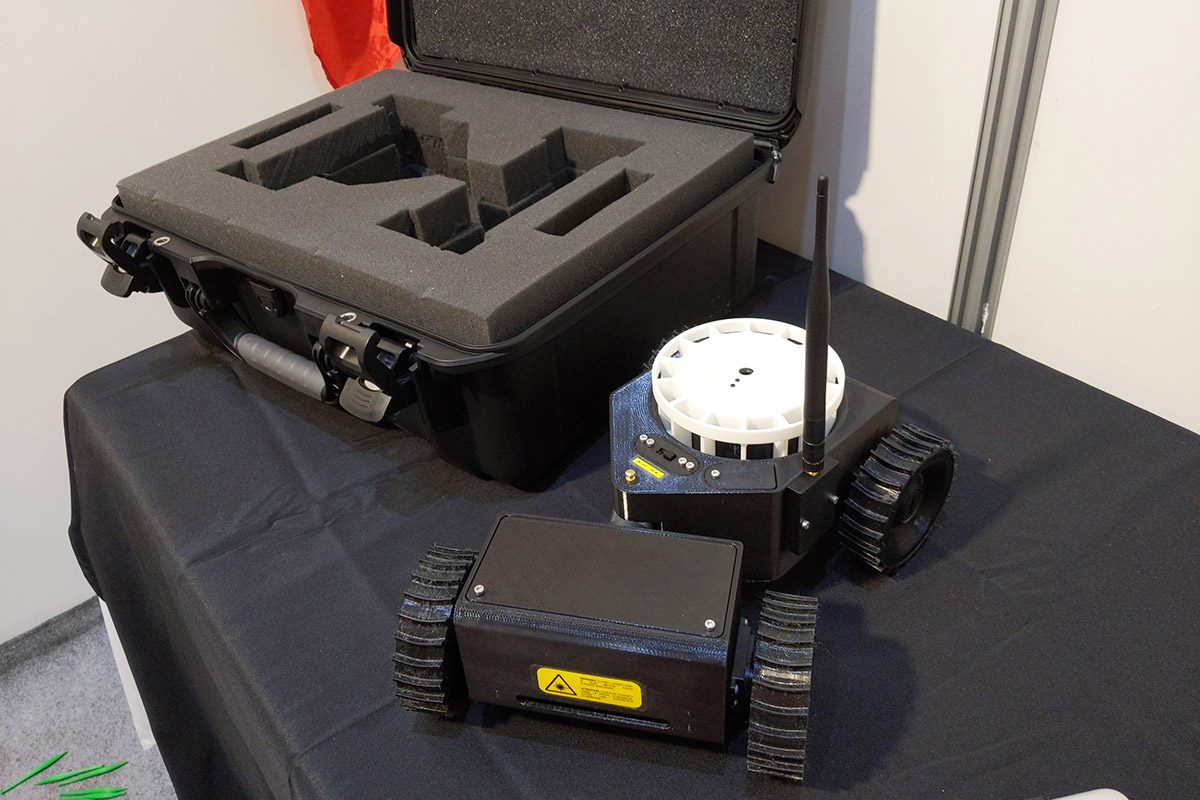

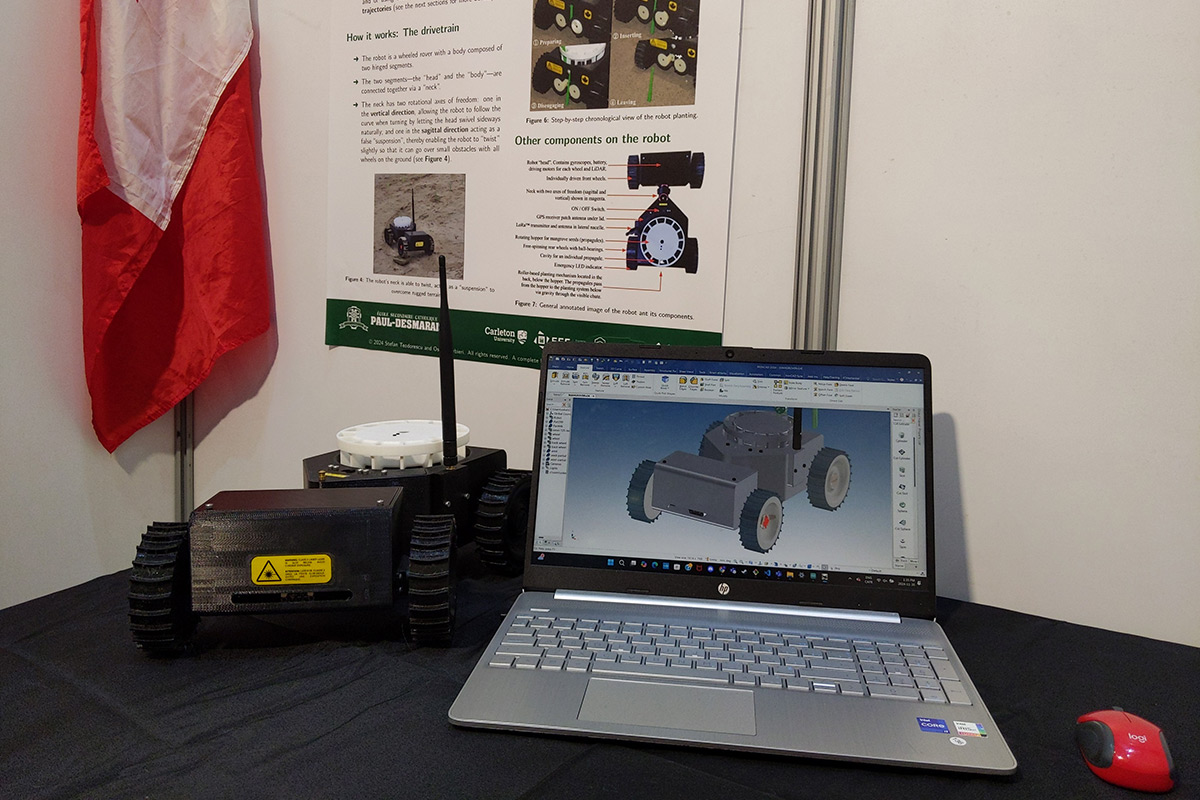

The four-wheeled Mangrover was built out of parts made from three different types of plastic, using 3D printers Teodorescu had at home. It operates within a geofenced area, zigzagging through the space to plant seeds 50 centimetres apart from one another on a route dictated by GPS and inertial measurements.

Teodorescu and Barbieri tested their prototype on an Ottawa River beach that replicates the type of sandy or marshy soil where mangroves grow. It worked well, depositing its payload of 15 seeds into the ground.

Even though Teodorescu has no immediate plans to keep developing this robot, he knows that future iterations will have to be larger so they can carry more seeds.

“Everything I learned from this experience could be applied to future projects,” he adds.

“And if somebody asked me to keep working on it, I wouldn’t say no.”

Carleton’s Atmosphere and Opportunities

One of the reasons that Teodorescu is moving on from the Mangrover is that he’s busy wrapping up his first year of university classes and getting ready for exams.

He chose Carleton because he felt a strong connection to the campus and community — people were friendly and the atmosphere was relaxing, despite the academic intensity of engineering.

Although still in first year, Teodorescu has already been interacting with his professors. He joined the amateur radio club, where he frequently meets with faculty members, and will be working as a research assistant for a prof this summer.

“There are a lot of opportunities at Carleton that I don’t think I would have gotten at other universities,” he says.

Considering what he’s accomplished so far, it’s exciting to think about where these opportunities might lead.

Thursday, April 10, 2025 in Aerospace, Engineering, Innovation

Share: Twitter, Facebook