By Dan Rubinstein

Photos by Chris Roussakis

One of the few reassuring science stories circulating since the coronavirus pandemic abruptly threw Canada into lockdown mode in mid-March is that there is no evidence of people getting sick through contact with the contagion in water.

That doesn’t mean that SARS-CoV-2 — the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019, or COVID-19 — isn’t present in wastewater, rivers and lakes, just that the virus is not contagious in water, especially drinking water than has been filtered and disinfected by treatment plants.

Prof. Banu Örmeci

But the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater does present an opportunity for researchers to monitor its incidence in a community — and a project led by Carleton Civil and Environmental Engineering Prof. Banu Örmeci, the Jarislowsky Chair in Water and Global Health and director of the university’s Global Water Institute, aims to help develop an “early warning system” that could alert public health authorities about an outbreak before people start to show symptoms.

“This research could lead to a great non-invasive tool for COVID-19 surveillance and monitoring,” says Örmeci.

“It could give us a very good idea about the prevalence of the disease in a community.”

Work Continues Outside Lab

Örmeci and Carleton research associate Richard Kibbee will be testing samples of both raw sewage and processed water obtained from treatment plants. They’re looking for SARS-CoV-2’s genetic material, its viral RNA.

This will allow them to establish the occurrence, fate and persistence of SARS-CoV-2 before and after treatment.

Although Örmeci and Kibbee don’t have access to their lab right now, they are already collecting and freezing samples that can be analyzed later to provide baseline data from the period when the virus was at peak, as well as gathering ongoing real-time data in the weeks ahead.

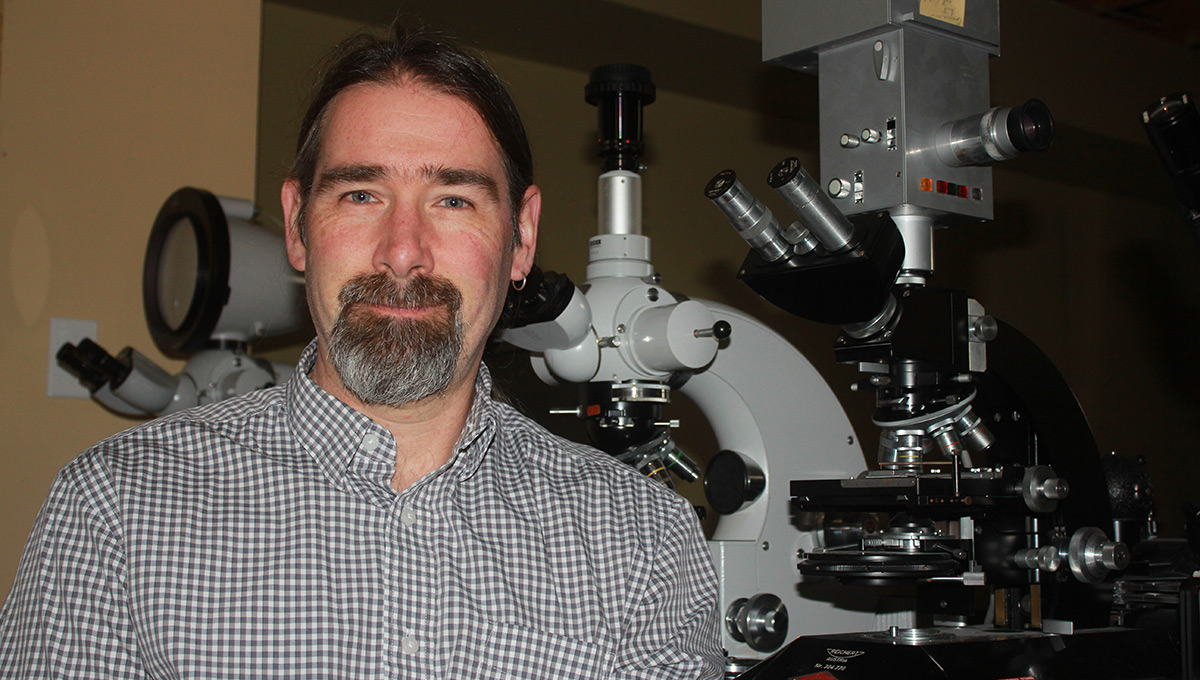

Richard Kibbee

“It’s inconvenient to not have lab access right now,” says Kibbee, “but that doesn’t stop the research. It’s important to archive the samples now.

“We have the facilities and the expertise to work on this project,” he continues.

“We have the molecular and microbiological tools to do this.”

“One treatment plant can capture wastewater from more than one million people,” Gertjan Medema, a microbiologist at KWR Water Research Institute in Nieuwegein, the Netherlands, says in an article in Nature’s news section.

“Studies have also shown that SARS-CoV-2 can appear in feces within three days of infection,” the story says, “which is much sooner than the time taken for people to develop symptoms severe enough for them to seek hospital care — up to two weeks — and get an official diagnosis.”

In the past, another Dutch research centre, the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, has successfully “monitored sewage to detect outbreaks of norovirus, antibiotic-resistant bacteria, poliovirus and measles.” And according to University of Arizona environmental microbiologist, Charles Gerba, “Wastewater monitoring has been used for decades to assess the success of vaccination campaigns against poliovirus.”

Preparing for the Next Wave

Because a potential coronavirus vaccine is months if not years away, and because SARS-CoV-2 will likely come back in waves, “there is a need to keep an eye on the virus and to watch for an increase in levels,” says Örmeci, “so we can stop outbreaks before they spike up.

“We are able to detect the presence of the virus in the community before there is a confirmed case of the disease in the community,” she adds.

“There are a couple of weeks that are extremely critical. Having this advance forecast will allow health-care practitioners to be aware and ready.”

Örmeci and Kibbee are working with industry and government partners and are seeking additional support for this research, which meshes with other wastewater and drinking water projects they’ve collaborated on over the last five years, including work on waterborne pathogens and effective ways to disinfect contaminated water.

All data and findings from this work will be synchronized with results from at least a dozen similar studies around the world, says Örmeci, who is part of the International Water Association’s COVID-19 task force.

This is part of a widespread global effort to share as much epidemiological information about SARS-CoV-2 as possible, she explains. Because the virus is new, methods that will help researchers understand it and deal with it are still being developed.

And even though contracting coronavirus through water is not a concern, projects such as this one shine a spotlight on the need to safeguard one of our most vital resources.

“We need to protect the quality of our water supply and do a better job with wastewater treatment,” says Örmeci.

“I would like to thank the Jarislowsky Foundation for their support and for providing the resources that enabled this research.

“Waterborne pathogens and chemicals are usually the main issues, but our focus has shifted right now to monitoring of emerging pathogens like SARS-CoV-2 that we know very little about.”