Lead image by BrianGuest / iStock

By Elizabeth Kane

Slow and steady wins the race, according to The Tortoise and the Hare, but time might be running out for some of Ontario’s turtle populations.

The province is home to eight species of turtles – nearly all of which have been classified as threatened or at risk of being threatened.

The biggest challenges turtles face come from habitat loss and road mortality, but Carleton University researcher Christina Davy is working to increase the number of these delicate populations by digging into all potential threats to turtles and their hatchlings posed by humans, parasites and predators

Davy is the recipient of $290,615 from Ontario’s Species at Risk Stewardship Program, dedicated to studying the vulnerability of endangered Ontario turtles and identifying knowledge gaps over the course of three years.

“I am thrilled to receive this support for conservation work from the province,” says Davy, a professor in Carleton’s Department of Biology.

Seismic Impacts on Egg Success

Davy’s research is taking a multi-pronged approach to assessing potential threats and challenges when protecting turtles. One of these threats is the vibrations in the ground from human activity and the potential impact on turtle eggs.

“We know turtles like to lay their eggs on the sides of roads, but we don’t know whether the exposure to that ongoing vibration during incubation is a problem,” says Davy, explaining seismic vibrations can be generated by a variety of sources, including hydro dams, construction sites and wind turbines.

“We’re hoping that none of those sources actually pose a threat to developing turtle eggs, but this is something that we want to better understand.”

The team is assessing the potential impact of vibrations as they recreate low-level seismic conditions in the lab and assess the success of eggs incubated with and without exposure to vibrations.

Protecting Turtles from Parasites and Predators

Threats to turtles can also lie under the shell.

“We know that parasite loads can affect reproductive success,” says Davy. “They can affect the number of eggs that an animal produces or how well those eggs manage to hatch.”

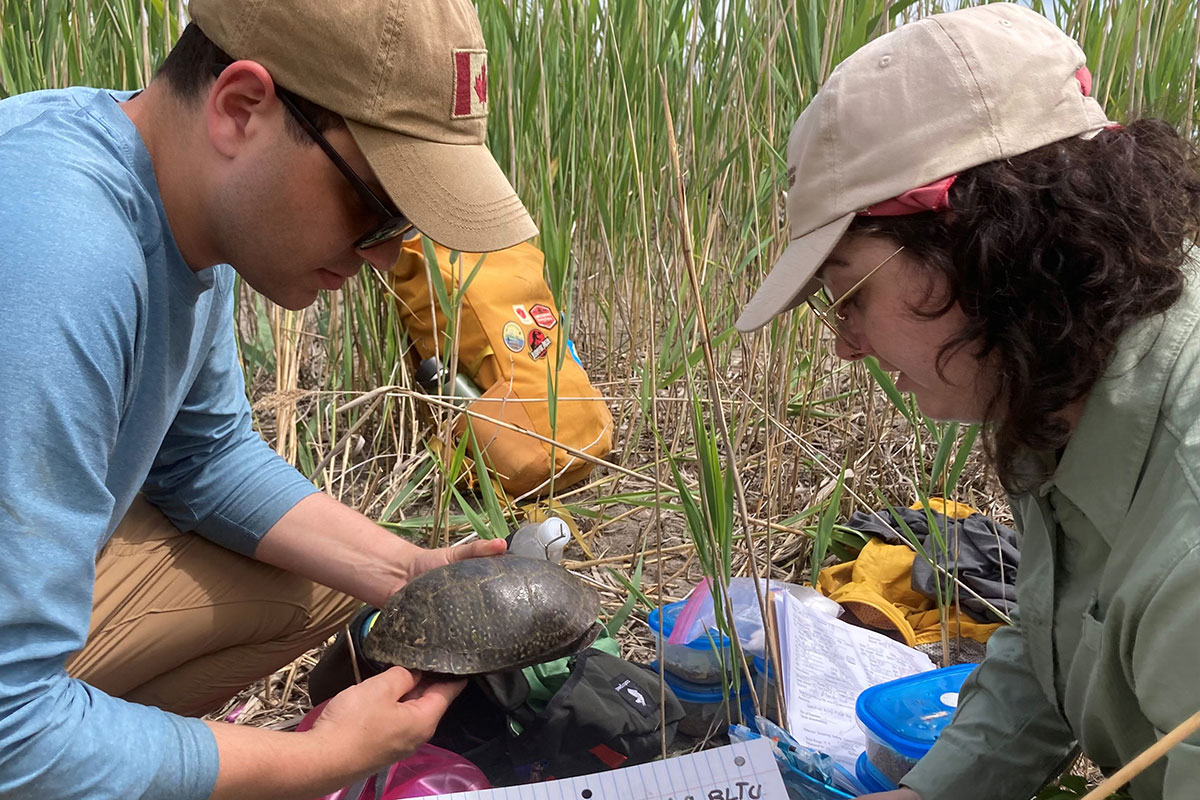

Currently, there is a knowledge gap regarding the impact of parasites on turtle reproduction. Davy’s research team of students and recent graduates is tackling this by collecting samples from turtle population surveys to test the blood for parasites.

“We can use DNA barcoding methods to screen those blood samples for all the different parasites we might be interested in,” she says.

Turtles are especially vulnerable before they hatch, with local predators like racoons and possums targeting their nests for eggs. Davy’s team will be giving the future hatchlings a leg-up on the food chain by using incubators to protect the eggs using a practice called “head-starting.”

“Nest predation is a real threat to turtle recruitment,” says Davy. “In places with very high numbers of predators, we can protect endangered eggs by digging up the nests before the raccoons can get to them and moving them into incubators that we have set up on site.

“My team and I have been doing this work for over a decade, and we have ensured the safe hatching and release of thousands of endangered spiny softshell and Blanding’s turtles.”

Testing Turtles for a Warming World

While the practice of using incubators for nests is an established one, the best temperatures to use for turtle incubation in Ontario are uncertain.

To fill this knowledge gap, the team is testing a range of five incubation temperatures that are all safe for developing eggs. They are comparing how long it takes eggs to hatch at each temperature, and the size of the hatchlings. The team will also test how long it takes hatchlings from the different incubators to flip themselves over when gently turned upside down. This research will inform best practices for incubator conditions to support the success of turtle eggs.

These results can help predict the effects of ongoing climate change on endangered turtles.

“As summer temperatures continue to rise, turtle nests experience warmer incubation conditions,” Davy says.

“This study will help us understand how rising temperatures affect hatchling fitness, which can affect population growth.”

Research Informs Policy and Practice

As part of this research, Davy’s team is working closely with Ontario Parks, the Canadian Wildlife Federation and the Ontario Turtle Conservation Center, and collaborators at Environment and Climate Change Canada.

The Carleton researcher’s findings will help inform policy and practices used by governments and conservationist groups protecting turtles throughout Ontario.

“If we find that these potential threats are real barriers to the recovery of turtle populations, we can come up with practical solutions that can be implemented in the field,” says Davy.

“The end goal is to inform policy and the recovery of these species.”

Looking ahead, Davy is clear that the biodiversity crisis in Ontario can be solved and work to achieve this goal needs to get underway.

“I’m hoping that this research will be part of moving in that direction.”

Thursday, September 26, 2024 in Biology, Environment and Sustainability, Research

Share: Twitter, Facebook