By Dan Rubinstein

Photos by Chris Roussakis

On October 4, 2017, the Ottawa Police Service issued a warning about the presence of the potentially deadly opioid fentanyl and the even more potent fentanyl analog carfentanil in street drugs believed to be heroin.

The drug samples — which turned out to contain no heroin — were seized by officers that July 31 and Aug. 1, but police and public health officials had to wait two months for Health Canada’s test results.

Carfentanil mixed with other controlled substances https://t.co/PpiwJwKaXT Please visit https://t.co/yuXLKSIu6N #ottnews

— Ottawa Police (@OttawaPolice) October 4, 2017

That long lag, and the heightened risk of overdoses and deaths among users exposed to tainted drugs amid North America’s unprecedented opioid crisis, are the target of a groundbreaking partnership between researchers at Carleton University and the University of Ottawa that is piloting the use of a portable mass spectrometer to test drug samples at the Sandy Hill Community Health Centre (SHCHC) supervised injection site.

The 22-pound bread maker-sized machine, the first of its kind, can provide the precise “chemical signature” of a substance based on the mass of its constituent molecules, in less than 20 seconds.

In other words, it can rapidly reveal exactly what is in a drug from a trace sample no larger than a single drop of liquid. And nobody else in the world is using this technology in this way.

Preventing opioid overdoses before they happen

Clients who come to the injection site just off Rideau Street will be asked if they want their drugs checked before they use — and will told exactly what’s in their syringe.

If it contains fentanyl or carfentanil, or another dangerous substance, including slightly modified opioid analogues, this information could convince them not to shoot up or prompt health centre staff to be on standby with naloxone for a potential overdose. And if testing exposes a pattern of bad drugs circulating through the city, officials can quickly distribute a widespread alert.

“This is potentially the most impactful research I’ve ever been involved with,” says Carleton Chemistry Prof. Jeff Smith, director of the Carleton Mass Spectrometry Centre (CMSC), who is helming the technology part of the project in collaboration with principal investigator Lynne Leonard from the University of Ottawa’s School of Epidemiology and Public Health.

“This is an opportunity to bring together analytical chemistry and an extremely pertinent social science question,” continues Smith, “and could lead to significant insights into how to address the opioid crisis. This is one of the things we can do as scientists — we try to help figure out the most effective way to address a problem.”

A crisis that is ravaging the continent

There were 2,946 apparent opioid-related deaths in Canada in 2016, according to Health Canada, and at least 2,923 from January 2017 to September 2017, of which 92 percent were accidental. In the latter period, more than 70 per cent of accidental apparent opioid-related deaths involved fentanyl or fentanyl analogues, compared to 55 percent in 2016.

In Ontario, opioid-related deaths increased by 52 per cent from January 2017 to October 2017 compared to the same period the year before, the provincial government reports, and emergency department visits related to opioid overdoses jumped 72 per cent in 2017 over the previous year.

Forty-eight people died of unintentional overdoses in Ottawa in 2015, the latest full year for which numbers are available.

Prof. Jeff Smith

These statistics paint a dire picture of a crisis that is ravaging the continent — a perfect storm resulting from over-prescription of high-dosage opioids with pharmaceutical companies downplaying the side effects, which led to high rates of addiction, followed by a regulatory crackdown on opioids that sent waves of people toward street drugs such as heroin.

“This crisis,” says Leonard, “is the consequence of a series of inter-related events,” which has led people to seek “unregulated drugs of unknown content, quality and effect.”

“It’s a unique crisis,” adds Rob Boyd, director of the SHCHC’s Oasis program, which provides medical and social services for people living with or concerned about HIV and/or hepatitis C, and who encounter barriers to services because they use street drugs, have a mental illness, are homeless or are involved in the sex trade.

“Nobody else has faced a problem like this before. If you’re buying heroin, assume that there’s fentanyl in it.

“It’s very clear that something is different in Ottawa and has been going on for the last 12 months. We think it’s absolutely critical to give people an opportunity to understand what’s in the drugs they’ve purchased.”

Gathering information that could drive policy change

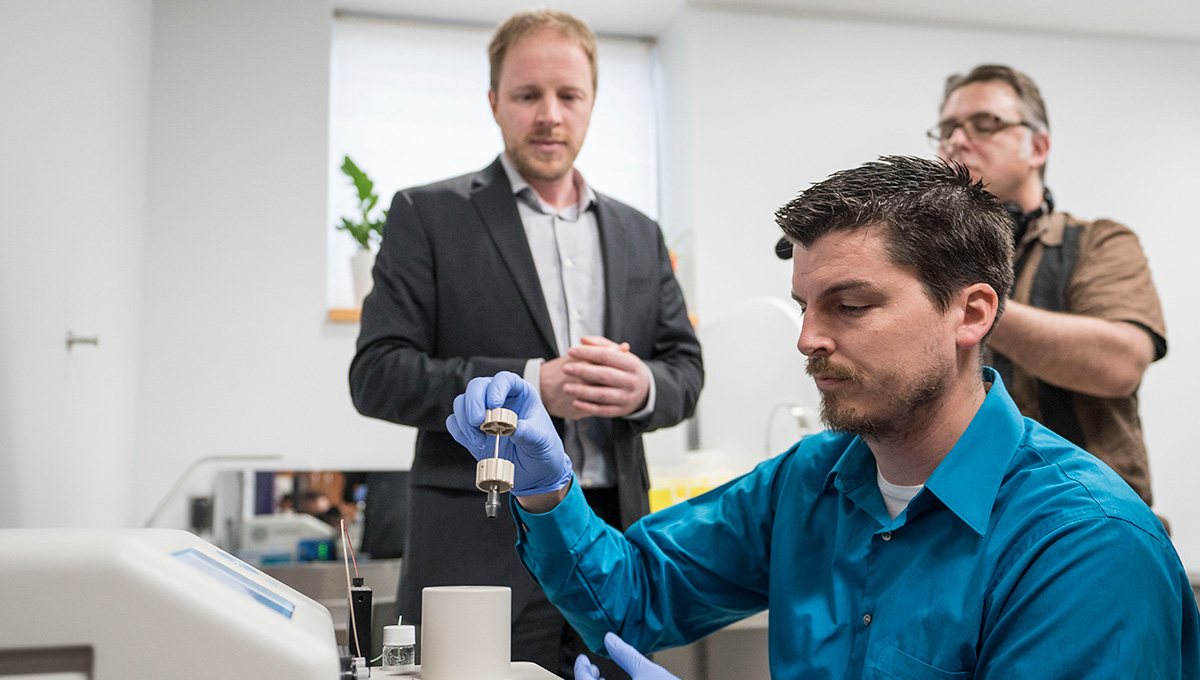

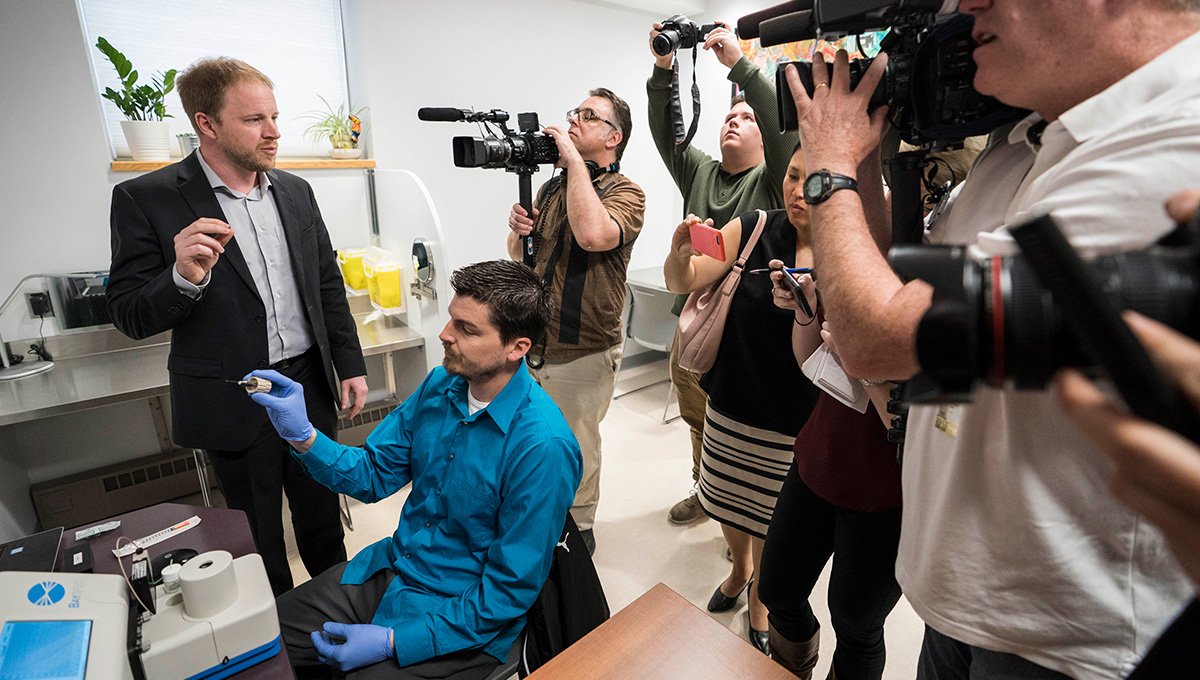

In the Sandy Hill supervised injection site, which resembles a doctor’s examination room, CMSC lab manager Karl Wasslen dips a wand with a small loop on the end into a drop of liquid on a microscope slide.

He slides the wand — with two microlitres of the liquid now forming a lens on the loop — into a port on the mass spectrometer. Almost immediately, red lines spike on a graph on the machine’s display window, indicating the presence of fentanyl and cocaine.

Leonard and Smith’s project, which is supported by $500,000 over three years from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, could lead to mass spectrometry testing at more locations in Canada, and at the same time it is gathering information that could drive policy change.

Focus groups with different types of drug users were conducted to help design the project.

“This is something that’s really needed,” says Leonard. “It’s the right intervention at the right time.”

The portable mass spectrometer set up in the Sandy Hill site in early May cost US$130,000, but the price will likely drop as demand grows.

CMSC lab manager Karl Wasslen conducts a test

It’s much more accurate than fentanyl strips, which only detect one drug, can produce false negatives and have elicited a Health Canada advisory. And although Smith has not personally used other high-tech methods of drug analysis like the light-based Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometer (FITR) being tested in Vancouver, he calls mass spectrometry the “gold standard” instrument for analyzing complex drug samples and believes it has the capacity to be more accurate than FITR.

More work remains to be done to develop and refine the methods used to determine not only what substances but also how much of each substance are in the samples being tested, which is “one of the hurdles of any new technology,” says Smith, “because there’s no existing literature to follow.”

But all project participants are optimistic that it will have an immediate — and potentially profound — impact.

“We anticipate that people may adjust their behaviour based on what’s in their drugs,” says Boyd. “People in the community are angry and afraid because they’re seeing so many deaths.”

“In this end, this will save lives,” says Christine Lalonde, a member of the SHCHC’s community advisory committee, which was tasked with finding out what people in Ottawa’s drug user communities think about this project.

“We don’t have two months if there’s a bad batch of drugs going around the city.”

Friday, May 4, 2018 in Faculty of Science, Research

Share: Twitter, Facebook