By Jonathan Malloy and Loleen Berdahl

Every year, a new wave of students begin PhD programs in Canada, often aiming for a future academic career. Yet despite hopeful beginnings, large numbers don’t achieve this goal. Many PhD students do not complete their programs, often dropping out after investing years of time.

Those who do finish face a highly competitive academic employment market, as the number of annual PhD graduates exceeds the number of available academic openings in all but a few specialized areas of study.

Universities are increasingly aware of this imbalance. But their responses are slow and uneven. Our research helps to explain why, and we argue that PhD students must take their own initiative to prepare for diverse career outcomes.

One-fifth in academic positions

A 2015 Conference Board of Canada study found that only about one-fifth of Canada’s PhDs end up in academic positions. Another study found that only one-third of recent Ontario PhDs found academic jobs anywhere in the world.

While some PhDs quickly find satisfying work in other fields, many graduates end up in precarious limited-term or part-time teaching positions, increasingly disillusioned by the diminishing hopes of landing the full-time academic job they so desire.

This cycle continues year after year with new cohorts. Somewhat perversely, universities and colleges have also become increasingly reliant on this part-time, flexible workforce to deliver more and more of their teaching.

This imbalance between the number of PhDs and available full time positions has become disruptive. In 2018, part-time instructors paralyzed York University in a strike over demands for more full-time faculty positions. The 2017 Ontario college strike was driven by similar issues.

PhD competencies still valuable

Yet Canada still needs PhDs — just not exclusively for academic jobs. The deep skills and competencies developed in doctoral programs are of value in today’s complex workforce.

The challenge is shifting PhD students and programs away from a narrow focus on academic careers. Further, many PhDs need assistance to match the skills that they’re developing to non-academic career paths.

Universities and academic bodies are responding to this challenge in several ways. The Canadian Association of Graduate Studies (CAGS) has called for a rethinking of how PhD programs are designed. Professional development programming for PhD students has also increased, helping them build their job skills and career aspirations beyond academia.

Some universities are also investing resources to follow where their PhD students end up. The University of Toronto and the University of British Columbia tracked the career outcomes of their recent PhD graduates, publishing the results online.

Slow and uneven response

But the overall response remains slow and uneven. Our research identifies two reasons for this. The first is organizational.

Universities are decentralized institutions with many autonomous parts.

Even when the motivation for change exists, resources are dispersed and co-ordination is challenging. Departments, graduate faculties, career centres and other bodies, including governments and research councils, all hold different parts of the puzzle. With different missions and resources, they struggle to fit them together.

The second factor we find in our research is attitudinal. Since most faculty have spent their own careers inside academia, it is difficult for even the most well-meaning to advise students on other options. This contributes to a mindset, conscious or not, that career success is defined primarily by becoming a professor.

Most professors are aware that the number of PhD students graduating exceeds available academic jobs. But there is still a strong “academia-first” mentality that sees other options strictly as Plan B backups. This dilutes any commitment to making structural and programmatic changes.

No incentive to close admissions

Even if some institutions or faculty decide that they’re taking on too many students, there’s little incentive to be the first to stop. Universities increase their prestige and rankings by bolstering their graduate research activity. And individual faculty gain status by supervising more students.

Finally, universities are responding to market demand. After all, students continue to apply for PhD programs. As top students who did well in their earlier studies, many believe they can beat the academic job odds. Not until later do they realize that everyone else is thinking the same way. So the system perpetuates itself, but for many reasons, none of which are easy to change.

All this leaves students in a challenging position, because doing a PhD can still be a good option, and Canada needs skilled researchers and a more educated workforce.

Don’t postpone planning

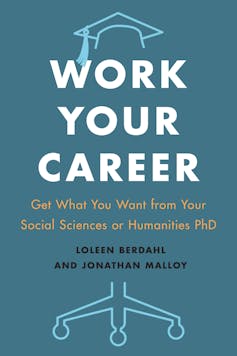

Consequently, we argue in our book Work Your Career that it is critical for PhD students to make the most of their personal opportunities and prepare for a greater diversity of career options.

Students should inform themselves about doctoral job market realities as early as possible — ideally before deciding to start a PhD. They should also be skeptical of any contemporary rosy forecasts, such as those the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada offered in 2008 when projecting a faculty hiring boom.

Students must also recognize and resist the pervasive “academia first” culture that lead many to postpone preparing for a broader range of careers until later, and purely as a backup.

Actively seeking and pursuing professional development opportunities as early as possible in their programs, along with conducting informational interviews, especially through alumni networks, is crucial. So is pursuing non-academic writing and research opportunities. These activities give students options and empower them to prepare simultaneously for both academic and other careers.

Ultimately it is up to universities to create a more sustainable model of PhD education; the burden should not rest solely on students.

Universities and governments also have an opportunity to play a more co-ordinated role, reconciling the demands for ever-greater research intensity and a more educated workforce with the realities and current state of doctoral education.

Yet students cannot afford to wait for this to happen. By exercising their own agency, students can avoid resting their career prospects solely on the fickle academic job market.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Carleton University is a member of this unique digital journalism platform that launched in June 2017 to boost visibility of Canada’s academic faculty and researchers. Interested in writing a piece? Please contact Steven Reid or sign up to become an author.

All photos provided by The Conversation from various sources.

![]()

Wednesday, October 9, 2019 in The Conversation

Share: Twitter, Facebook