By Adam Landry

Photos Courtesy of Paul Austerberry

This past awards season, Carleton architecture alumnus Paul Austerberry (BArch/89) scored a double feature for his work on Guillermo del Toro’s The Shape of Water.

After a big win at the 2018 British Academy of Film and Television Awards (BAFTAs) in February, Austerberry went on to walk the red carpet at the 90th Academy Awards in March, ultimately taking home the Oscar for Best Production Design.

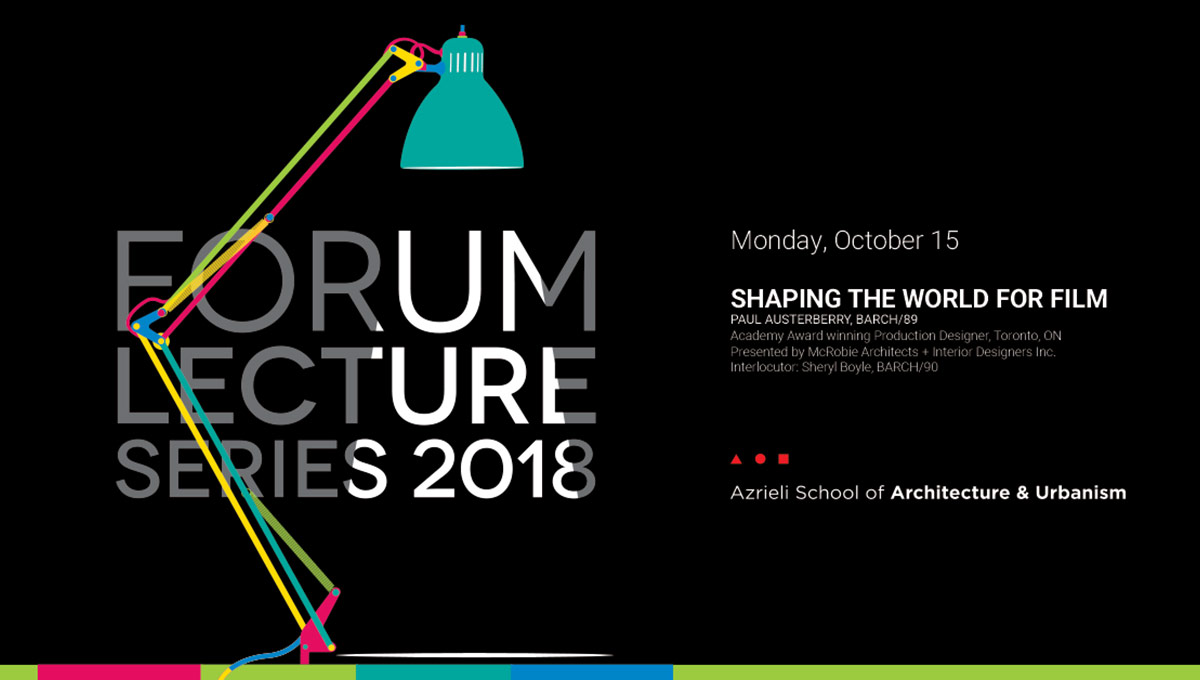

On October 15, 2018, Austerberry will be returning to Ottawa for the Azrieli School of Architecture and Urbanism’s esteemed Forum Lecture Series, where he will deliver a special talk on Shaping the World for Film as part of the school’s ongoing 50th anniversary celebration.

Where were you when you first learned you had been nominated for your work on The Shape of Water? How did you react when you received the news?

I was actually in Ottawa at the time, as I had been in town for a panel discussion with (Carleton’s) School of Architecture as part of its 50th anniversary. I was in a hotel lobby waiting for a taxi to the airport when the news broke and was super excited as you can imagine, but I was sitting in a public place so I couldn’t really jump up and down!

Did you expect the film would receive so much attention at this year’s Academy Awards?

When we were first designing and prepping the film, I don’t think I could have predicted it, as the storyline is so strange and our two heroes don’t speak (and one of them is a fish man). However, when I saw Sally Hawkins’ work on the first day of shooting, I knew it was going to be great. Still, I wouldn’t have expected a genre film to be so well received by the academy.

How did you feel when your name was called and you realized you had won? What was it like to walk up on stage and accept your Oscar?

It was incredibly nerve-racking for the first hour while we were sitting in our seats waiting for our category to come up. When they finally listed the nominees there was a slightly bigger cheer from the audience for our film, which we thought was a good sign. When we actually heard our names, it was both exhilarating and terrifying, since we knew we were about to get up and speak in front of a massive audience.

How did you first break into the film industry?

After graduating from Carleton, I moved to Toronto to work at an architectural firm and happened to make friends with a number of people who were involved in the film industry. Over the course of the next two years, I worked within that firm before deciding to do some travel in Asia for about eight months. When I returned, there was a recession in the building industry, so I decided to volunteer in an art department on the recommendation of one of my friends. Four days into that, a paid job became available and I was in.

Where do you begin after you’ve read a script?

The first thing I always do is break down the script into all the different locations it describes. Then you can decide which ones might be able to be found as a practical location, which ones could be created by heavily modifying an existing location, and those that need to be entirely constructed in the studio.

In an interview with the LA Times, you mentioned how the Brutalist-style architecture of certain buildings at Carleton influenced your vision for elements of the film, such as the government lab where the creature is held captive. Can you elaborate?

I was referring to the style of architecture that Carleton’s Architecture Building was built in and was very common in the 1950s, ‘60s, and ‘70s for institutional buildings. I had wanted to contrast the more romantic world of Sally Hawkins’ character’s apartment above an old theatre-turned-movie-house from the 1890s with something that featured harder lines and harsher materials like concrete.

Has your time at Carleton impacted your other projects? Were there influential professors or memories that you’ve drawn from?

I think that my time at Carleton has impacted pretty much all of my film projects, as the skills we learned there were really about how to look at the world around you and the visualization of three-dimensional space. We had a lot of inspirational professors, as well as an amazing array of world-renowned visiting critics such as Frank Gehry and Zaha Hadid shaping our education.

What was it like working with legendary fantasy director Guillermo del Toro? How were you able to translate his vision to the big screen?

It was a joy to be able to work with Guillermo, as he is such a visual director. He really celebrates the art direction in a film and it becomes an essential part of the storytelling. It was a difficult task to translate his vision as written on the page, as this film had a pretty small budget for the number of sets we had to generate. We shot for almost 60 days and all but 18 of them were on location – and even those locations required a substantial amount of modifications to suit the script and the 1960s time period.

How can the look of a film affect its narrative and how has your understanding of architecture helped you in establishing visual themes?

The look of a film can affect its story by creating a mood or feeling through the use of colour or texture and shape. Warm versus a cool colour palette, for instance, can accentuate a friendly versus a harsh environment. Softer architectural spaces can be more welcoming versus angular, sharp-lined architecture, which can sometimes feel more oppressive or aggressive. These are the kinds of tools we can use to help set the mood and enhance the story.

What kinds of challenges did you face once you had seen the screenplay for The Shape of Water?

One of the biggest challenges we faced once we read the screenplay was how to tackle the four main underwater sequences. In the end, we resorted to only submerging one small bathroom set in a specially constructed tank and using a “dry for wet’’ technique. Essentially, the old-fashioned method involved suspending the furnishing and actress by wires while filling the set with light smoke. Then we used multiple projectors to impose the caustic light, which travels through water onto the smoke and slowed it all down a bit. Elisa’s hair and nightgown were then animated digitally by our visual effects team, which also added particulate in the water, along with a few fish.

You’ve worked on films from a number of blockbuster franchises, including Resident Evil, Twilight and X-Men. How different is it when taking on smaller projects like The Shape of Water?

Every scale of film has similar problems and there never seems to be enough time or money to do what you initially plan. Often it takes a lot of thinking outside the box to make it all work. I think one of the things that made The Shape of Water successful is that everything within the film works so cohesively. The lighting, the props, the costumes and sets all work harmoniously colour-wise and a big part of that is that we didn’t have that many different locations or sets so we were able to control it all.

The Shape of Water’s Canadian connections are well known, especially with it having been shot in Toronto and Hamilton. What do you think the film’s success says about the state of the industry here in Canada?

I think it shows that there’s a lot to be proud about when it comes to the industry north of the border. Almost all of the crew members for the film were Canadian and everyone was very excited that we were able to compete with the best in the world this past awards season. I’d like to point out that on this film alone there were actually four Carleton grads working in the art department, including David Fremlin and William Cheng (first assistant art directors), Nigel Churcher (art director) and myself. There are plenty more throughout the industry in general as well.

Where does your Oscar live? Does he have a permanent home on display or is he stored away for safekeeping?

I don’t currently have a fireplace or a mantle, so Mr. Oscar sits in my living room on a live-edged walnut bench I made a few years back.

What has this Oscar meant to you personally or professionally? Have you gotten used to the title of ͞Academy Award winner?

Personally, everything still hasn’t fully sunken in yet. There were some incredibly well -crafted films this year and it was very fulfilling just to be able to stand alongside them. Professionally, I know it’s an amazing achievement and honour, as it represents the pinnacle of recognition within the Hollywood film industry. Hopefully that means I’ll get the opportunity to work on more prestigious films in the future that I otherwise wouldn’t have had the chance to.

You currently have some exciting films in pre-production, including the followup to last year’s wildly successful reboot of Stephen King’s It. Is there any added pressure in working on the sequel to a highly acclaimed film?

There is definitely a lot of excitement surrounding It: Chapter 2, so there’s a bit of pressure from fans to deliver an even better sequel. We know we have to recreate a lot of what was in the first film, but we also get to develop that world even further for the finale, which is fun.

How do you go about choosing the films you work on?

Ideally, you pick a project because you love the script and the people behind it. If I know about a particular film long enough in advance, as was the case with The Shape of Water, I’ll try to wait and stay busy working on commercials so that I’m not locked into other long -term projects. That said, more often than not, a script shows up at the last minute and you have to decide quickly whether to make a pitch for it or pass. Often you read a script one week, have a meeting the next and a week later, you find yourself boarding a plane to another part of the world where you’ll spend the next six to 10 months . . . just like that!

Thursday, October 11, 2018 in Faculty of Engineering and Design

Share: Twitter, Facebook