Lead image by sergeyxsp / iStock

By Audra Diptée

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. All photos provided by The Conversation from various sources.

Audra Diptée is an associate professor of history at Carleton University.

In 2011, the world learned of the secret British policy called Operation Legacy that was implemented in the 1950s. The goal of this policy was to remove incriminating documents from former colonies in the months before each one became politically independent.

Documents that might embarrass or damage the British government, police and military were either secretly removed or destroyed. This policy had an impact far and wide, and was implemented in British colonies throughout the Caribbean, Asia and Africa.

In an age where misinformation is everywhere, Operation Legacy provides us with an instructive example of the repercussions faced when people with power determine what information is available to interpret events of the past.

Kenya: the unravelling of a British lie

We know about Operation Legacy because of a case brought before the British High Court. Five elderly Kenyans accused the British colonial government of imposing a policy of torture and human rights abuses during a state of emergency from 1952-1960 instituted in response to a rebellion against colonial rule.

The case revealed the price many Kenyans paid as they fought against colonialism. At the core of the conflict was access to land. From the beginning of colonial rule in 1895, the British were aggressive in their efforts to displace Africans from their lands. The goal was to reserve the most fertile land for white settlement and farms.

By the 1950s, African resistance became more organized and intense. When the colonial government declared a state of emergency, Kenyans suspected of challenging British colonial rule faced even greater risks. The state of emergency gave colonial authorities a wide ranging set of powers — which included torture and other human rights abuses — to deal with the anti-colonialists.

The propaganda from the period is telling.

Privileging the colonizer’s narrative

Many historians of 20th century Kenya — but not all — overlooked or downplayed this colonial policy of violence. Some might argue they should be forgiven as there were no official colonial documents that revealed a British policy of human rights violations in Kenya.

But what happens when the absence of proof is really due to the deliberate removal of evidence?

Others might be inclined to think those historians did not look hard enough. They were only willing to believe the official colonial records even though there were Kenyans alive who could give oral testimony.

For the five elderly Kenyans, the irrefutable evidence was the scars they bore on their bodies. Make no mistake, the human rights violations were extreme. They even included castration. The Kenyans also had their memories. Yet, this mattered little for those historians who privileged official colonial documents above all else.

However, it was the work of historians David Anderson, Huw Bennett and Caroline Elkins that helped turn the court case around. Their research challenged the historical silence on colonial violence during this period.

In court, evidence was presented that colonial documents were deliberately removed and that the testimony of the elderly Kenyans was, in fact, credible. In December 2010, the presiding judge ruled that the British Foreign and Commonwealth office had to release all documents related to the case.

Once these documents were released and analyzed, the evidence was clear. The British colonial government sanctioned extreme abuses. We now know that over 80,000 people were imprisoned without trial and more than 1,000 people were convicted as “terrorists” and put to death by hanging.

Only eight white officers were accused of extreme abuse, and they were all granted amnesty. This includes the officer accused of “roasting alive” one Kenyan.

Shortly after the Foreign and Commonwealth Office was required to release documents concerning the case, an announcement was made in the House of Lords that files were also being held concerning 37 former British colonies. An independent audit revealed there were more than 20,000 files taken from former colonies.

Some files were also slated for destruction, and there is no way to know how many were destroyed.

Guyana: destroyed documents and a coup

The files that did survive were eventually transferred to The National Archives in London. They are now officially referred to as the “Migrated Archive,” a carefully chosen misnomer. Now that they are in the public domain, we have a better idea about the documents available for other former British colonies.

I am currently working on a project, Chained in Paradise, that explores the impact of Operation Legacy on the Caribbean. When the public was informed about the specific documents in the Migrated Archive, historian Richard Drayton was the first to point out there were no documents for British Guiana, present-day Guyana.

In other words, unlike in Kenya where some documents were hidden, in British Guiana they were all destroyed. Did Britain have things to hide concerning its colonial policies in British Guiana? The short answer is yes.

The Personal net

Approximately one year after Britain declared a State of Emergency in Kenya, it declared another in British Guiana in October 1953; six months after the colony’s first democratic election.

British troops were deployed to remove the elected Prime Minister Cheddi Jagan. The constitution of British Guiana was suspended and the British governor ruled for three more years. The area formerly known as British Guiana became the independent nation of Guyana in 1966.

Jagan was accused of being a communist and went to England to protest his removal. However, he and his allies were eventually placed under house arrest.

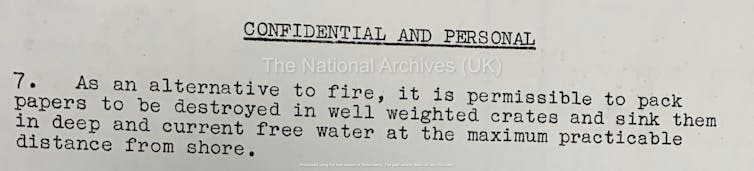

According to one document I have reviewed from the Migrated Archives, less than one month after Prime Minister Jagan was elected, records in British Guiana were incorporated into a secret system for hiding official correspondence. It was called the “Personal” net.

There are three things we can learn from these records:

1) As soon as British Guiana had its democratically held elections, plans were put in place for high levels of British secrecy. Not only was there to be no transparency, there was also to be high levels of duplicity.

2) Before political independence — in other words, when Britain was on the cusp of losing its political control — documents were to be destroyed so the incoming government would be left in the dark about the tactics of its former British colonizers.

3) The document below suggests that certain colonial records could be destroyed because there were copies in England. To date, no such documents have been released as part of the Migrated Archives. This raises questions about where those documents currently are and if they still exist.

History is about the future

In his book, The History Thieves, journalist Ian Cobain argues that Operation Legacy was implemented so that British colonialism would be remembered with “fondness and respect.” He is right, but there is more to history than what we remember.

The long-term objective of Operation Legacy was to undermine future criticism of colonialism by sanitizing the past. That would make the transition from colonialism to neocolonialism easier as future economic relations with their former colonies would be negotiated without a proper historical understanding of Britain’s motives.

History was a powerful tool of the British empire, and it has been used to maintain unequal relations with its former colonies long after they attained political independence.

![]()

Thursday, March 21, 2024 in The Conversation

Share: Twitter, Facebook