By Dan Rubinstein

Photos by Chris Roussakis

Last spring, when Felix Denomme graduated from Carleton University’s Aerospace Engineering program and got a job at Ottawa’s B-Con Engineering, he was excited about using his education and experience to fine-tune optical systems the company manufactures for communications satellites.

But a couple of weeks ago, Denomme got a chance to start on a new project that will produce much more immediate — and visible — results.

Felix Denomme

After talking to an emergency room (ER) nurse he knows through his side gig playing bass drum in the RCMP pipe band, B-Con founder and owner Brian Creber decided to rejig about half of his company’s operations and begin making personal protective equipment for health-care workers who are on the front lines of the coronavirus pandemic.

Creber had a chat with Denomme and they ruled out masks and valves for ventilators before settling on adjustable, washable and reusable plastic face shields.

Thanks to connections with other local manufacturers and some Carleton students who have 3D printers at home, including Brian’s son Bill, B-Con has already blazed through five iterations of its prototype, incorporated feedback from nurses, and expected to be making about 450 face shields a week by mid-April.

At his daily news conference on April 22, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau cited Denomme and the company as an example of Canadians reaching out to support each other during the pandemic and asking what they can do to help.

“It’s our responsibility as engineers to do whatever we can to help during this crisis,” says Denomme, who has two aunts who are nurses.

“I love working on space systems, but you don’t really see the benefits right away.

“One of the huge draws for people who go into engineering is that you get to be creative and apply your problem-solving skills to help people.”

3D Printers Key to Face Shield Project

B-Con, which Brian Creber launched in 1988, has contributed to major international projects such as NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, working with larger integrators like Honeywell and MDA to supply reflective instruments for optical systems.

With communications satellites evolving over the years from radio to optical systems, the company has developed a solid niche. But it has also worked on other technologies, including automotive and aircraft displays, a line of commercial lenses and, in collaboration with Ottawa’s Med-Eng, face shields for bomb disposal suits.

Bill Creber

“It’s all fairly similar,” says Creber. “We’re familiar with the optical uses of plastic.”

Last year, when Denomme joined B-Con, he suggested that a lot of the components used by the company could be quickly and cheaply made using 3D printers instead of being machined. That shift is key to the health-care face shield project.

“With a network of 3D printers,” says Creber, “we could easily put together a supply chain.”

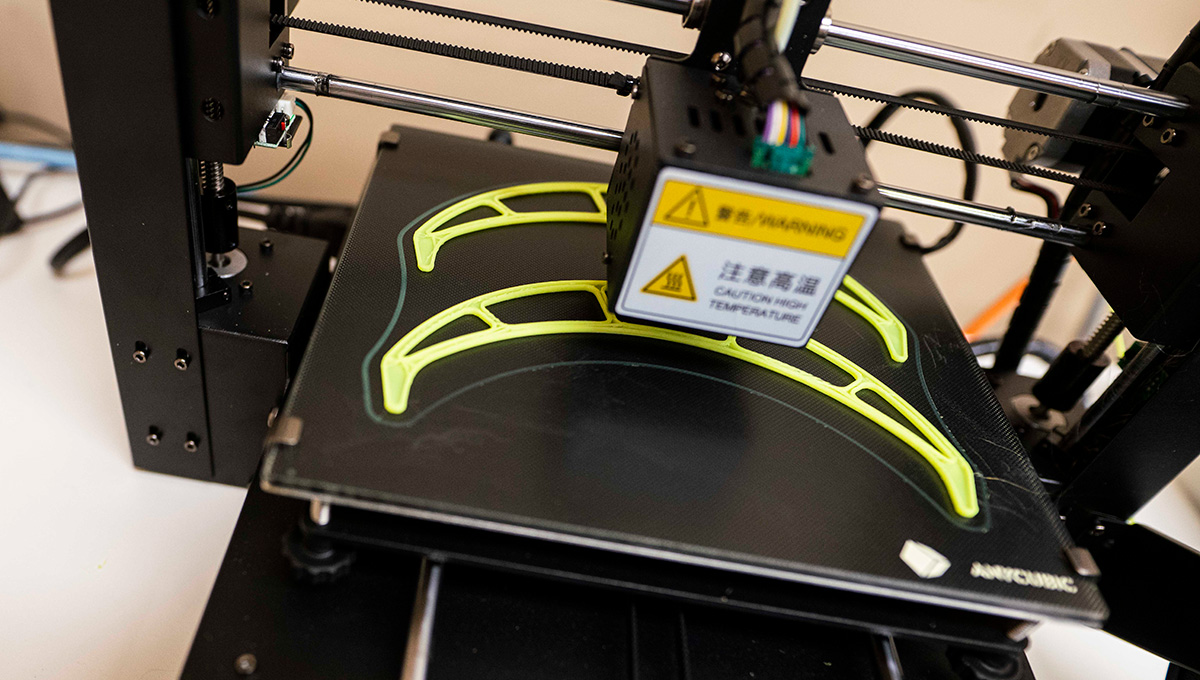

The yellow piece of plastic that holds the assembly together and attaches to a wearer’s head is being 3D printed, with local firm Canus Plastics producing the shields. The yellow piece is attached to the shield with nylon thumb screws, allowing the shield to be removed and sanitized.

“Students who have 3D printers are used to making all sorts of little widgets,” says Creber. “They’re finished classes and will have a hard time getting summer jobs this year, so it made sense to ask them. This would not have been possible 10 years ago.”

The 3D printers use spools of plant-derived biodegradable PLA plastic, which is heated into liquid form and then printed layer by layer to make the piece for the face shields. It takes about four hours to make a pair of pieces on one sheet, with B-Con paying $5 per piece (which requires about $1 of material to make).

Two Carleton students are part of the effort: Aerospace Engineering major Bryce Lippai and Bill Creber, who is nearing the end of his Computer Science degree.

“I got my hobby printer just a couple weeks ago to make 3D models and play around — I had no idea that I’d be using it for something like this,” says Bill, who, when he’s not studying, does freelance software and app design, work that has dried up this spring.

“It feels good to be able to help the community,” he says. “I’m just one cog in the machine. I’m not on the front lines, so this is the only way I can help.”

Shields Already in Use Outside Hospitals

B-Con will be making two sizes of shields: one for ER staff, and a larger version for operating room staff who need to be protected from a wider range of potential contaminants.

The company is working with federal and provincial health authorities to ensure the shields meet regulatory and certification requirements for hospital use, and they will sell for about $20 each, covering the company’s costs.

Some midwives in the Cornwall area are already using the shields to protect patients from potential germs, as are staff at a community lung health organization in Ottawa who visit patients with breathing difficulties in their homes.

“You can iterate item development very quickly with 3D printing,” says Denomme, explaining that engineers can also achieve certain “geometries” with 3D-printed plastics that would be difficult to do using traditional methods. “You can do a design, produce a piece, get rapid feedback and revise it right away.

“3D printing has become a fantastic tool — you can do everything from rapid prototyping to figuring out the interplay between mechanical structures, and then make the necessary adjustments needed to get something out into the field. Seeing technologies like this get implemented could change workflows and processes in different types of industries.”

At Carleton, during an undergraduate research project with Prof. Alex Ellery, Denomme worked on 3D-printed components for a robotic drill that was sent to the Arctic as part of the MICRO Life astrobiology collaboration with McGill University.

“Alex really pushed us to find creative outside-the-box solutions,” says Denomme. “He gave us problems that didn’t necessarily have solutions and we had to decide what to do on a short timeline. My time at Carleton really showed me what engineering can do, and how it can help society.”

“This pandemic is a wake-up call,” says Brian Creber, who has received inquiries about B-Con’s face shields from as far away as the United Kingdom but plans to limit distribution to the Ottawa area while sharing technical files and advice with other companies so they can make them on their own.

“We have to be able to make the health-care supplies and equipment we need within Canada. As a company, we had to do something. We can’t sew gloves. We can’t make masks. This is what we can do.”

Tuesday, April 14, 2020 in Aerospace, Computer Science, Faculty of Engineering and Design, Faculty of Science

Share: Twitter, Facebook