By Lisa Gregoire

Photos by Chris Roussakis

When Coastal GasLink says it got approval from 20 British Columbia First Nations to build a natural gas pipeline through Wet’suwet’en territory, they’re right. Elected band councils from reserves all along the route support the pipeline and the jobs and benefits that will flow to their people.

When five Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs say they don’t want the pipeline’s current route through their territory and that they have the legal right to say No, they’re right too. The Supreme Court upheld the Indigenous rights of those hereditary chiefs on off-reserve, unceded Wet’suwet’en land.

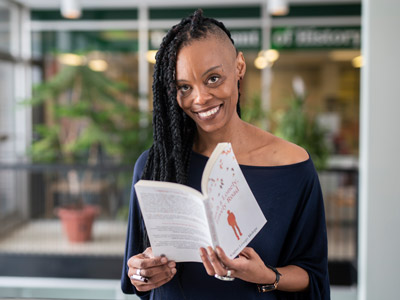

Gina Starblanket

Gina Starblanket, a Cree/Saulteaux assistant professor of political science at the University of Calgary and a member of the Star Blanket Cree Nation in Treaty 4 territory, delivered a talk at Carleton University on Feb. 26, 2020 organized by the Faculty of Public Affairs explaining how those truths, and more, can co-exist.

She also explained why most non-Indigenous Canadians, governments and businesspeople don’t understand what’s going on.

It’s because settlers and Indigenous peoples have different opinions about Canada’s creation story and the 11 numbered treaties that form its foundation.

The Promise of Royal Protection

When government agents sat down to sign treaties from 1871 to 1921, they understood it as a commercial transaction: the first peoples give up land and relinquish rights and they get benefits and protections in return.

The Queen, henceforth would take care of them, like dependent children, Starblanket explained to a packed lecture hall of students, faculty members and guests. The deal brought certainty and clarity to the settler government and, they hoped, pre-empted future conflict.

Setting aside well-documented cultural, spiritual and language differences, when Indigenous leaders sat down to sign an agreement they couldn’t read, they did not share the settler history and held distinct views of politics, economics, land and animals.

To them, a treaty was relational, like the many agreements they already had with neighbouring Indigenous nations. A treaty was the beginning of a relationship between equals to share resources and land, to take care of each other in times of need and to respect each other’s way of living in the world without undue interference.

“Treaties were not static or locked in time, but intended to shape the future political aspirations and transformations of partners,” she said.

In the wake of these treaties came a swift and catastrophic power shift that Indigenous peoples never wanted, Starblanket said, and a denial of sovereignty that they have been trying to recapture ever since.

“It represents a broader unwillingness to see political relationships with Indigenous peoples outside of settler frames,” Starblanket said. “And this in turn gives rise to the failure to properly understand, engage with, and theorize about—or generally take seriously—Indigenous people’s political positions.”

More than 100 years after the treaties were signed, this divergent view—that treaties were either a land deal or the start of a relationship—persists, and has led to a polarization of views across the country, as well as endless social, political and legal unrest.

Starblanket: “A Broader Unwillingness to See Political Relationships with Indigenous Peoples”

As typified by the B.C pipeline conflict, Indigenous peoples have been unjustly reduced to the Yes people and the No people, Starblanket said.

The Yes people are compliant. They follow settler rules, are willing to negotiate with Canadian governments and resource developers under predetermined terms and conditions, and thus support the national interest.

The No people are de-legitimized as radicals and activists for insisting on reframing negotiations on mutually agreed-upon terms; for weaving history and context into talks; and, for demanding conditions that equalize the status of both sides. They therefore pose a threat to the national interest.

The problem is, Starblanket said, the Yes people often have doubts and objections about how these deals go down but there is no mechanism through which they can articulate their reservations. And the No people often accept many aspects of proposed developments on their land, they just want to ensure their needs are also met and their concerns are properly addressed.

In other words, real “nation-to-nation” discussions are necessarily layered and complex and require, on behalf of settler negotiators, a deeper understanding of Indigenous culture and Canadian history, as well as an acknowledgment of the sovereign rights of Indigenous peoples to use their world view to frame and inform those discussions.

Canadian government officials don’t have to go far for a road map, Starblanket said. More than 250 years ago, King George III outlined how treaties should be negotiated between the Crown and Indigenous peoples, and how disputes should be resolved, in the Royal Proclamation of 1763.

“Indigenous people fought very hard to ensure that those principles of treaty making were recognized in the Constitution of Canada, that they formed part of constitutional law,” she said.

“We have these processes of dialogic interaction, negotiation and dispute resolution when problems arise. We’ve sort of lost sight of those processes.”

This talk was hosted by Carleton’s Faculty of Indigenous Policy and Administration. Learn more here: https://carleton.ca/sppa/ipa-2/.

Wednesday, March 4, 2020 in Faculty of Public and Global Affairs, Indigenous

Share: Twitter, Facebook