By Dan Rubinstein

Photos by Chris Roussakis and Michael Runtz

Michael Runtz could be dropped off pretty much anywhere in Ontario, blindfolded, and by sound, smell and feel, he would know where he was.

Algonquin Provincial Park — his favourite place on the planet — would stand out right away.

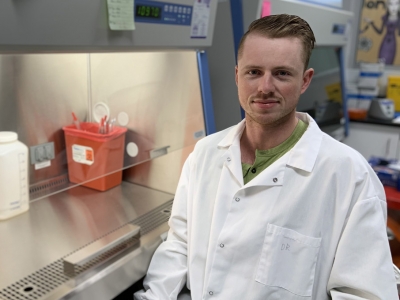

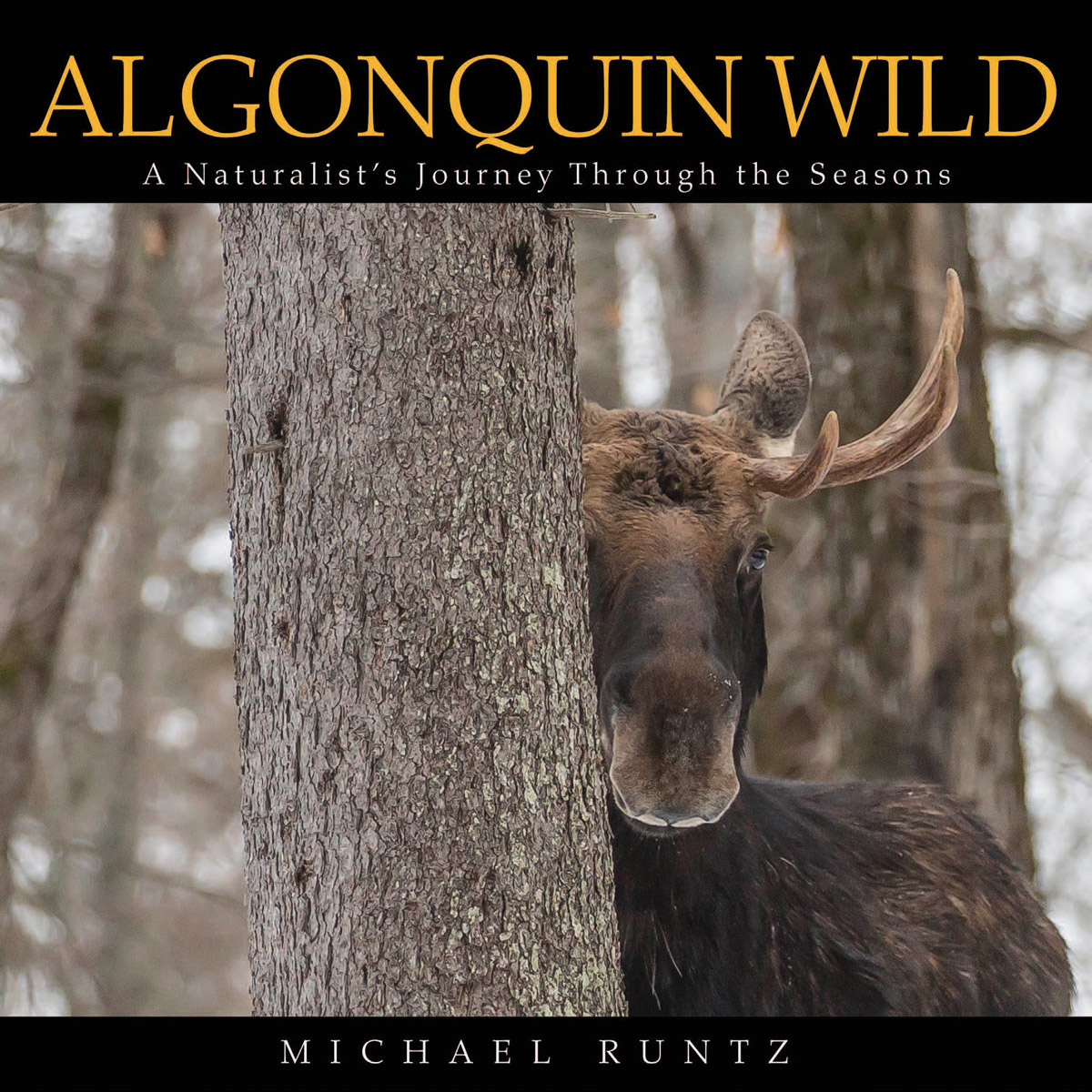

“Algonquin is different than anyplace I’ve ever been,” says Runtz, a Biology professor at Carleton University and the writer-photographer behind Algonquin Wild: A Naturalist’s Journey Through the Seasons, his 12th book, which was published late last year to coincide with the park’s 125th anniversary in 2018.

“In part, it’s the mixture of living things,” continues the world-renowned naturalist, who has spent time in dozens of Canada’s major parks from coast to coast to coast. “All the flora and fauna combine with the geology to create a unique blend of ecosystems, all coming together in Algonquin to create a distinct ambience or feel.”

Featuring more than 360 stunning photos and a chapter for each of the four seasons, Algonquin Wild takes readers inside Runtz’s intimate relationship with the park — a bond that was forged during family trips with his parents in the 1950s and evolved in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s when he spent 11 years working as an interpretive naturalist in Algonquin Provincial Park.

The park was also the focus of Runtz’s second book, Algonquin Seasons, published in 1993, and a quarter-century later, his appreciation of the 7,600-square-kilometre swath of southeastern Ontario has only deepened.

“I now have 25 more years of intimacy with and knowledge of Algonquin, and am taking much better photos now,” he says. “I now also have a fuller understanding of the abstract side of the park. I just like being in Algonquin. I love every minute spent outside there.

“I don’t consciously see things differently now. I just see different things.”

Some people might not consider Algonquin Provincial Park true wilderness because it’s so close to cities such as Toronto and Ottawa, but Runtz couldn’t disagree more.

“To me, true wilderness is a state of mind,” he says. “It’s experiencing nature going on its natural way, unencumbered by our presence. Hell, I can go to a backyard garden and watch a spider pull in a butterfly — to me, that’s wilderness.”

Which is an idea that Runtz gets across in the book, and an idea he has been sharing with students over more than 30 years of teaching at Carleton.

Experiencing Wilderness as a State of Mind in Algonquin Provincial Park

As one might expect, Runtz doesn’t have a favourite animal to photograph in Algonquin, nor a favourite season in which to experience the park, although he does admit to having a “flavour of the day” when he’s focused on a specific species or subject.

When he was working on his 2015 book Dam Builders: The Natural History of Beavers and their Ponds, for instance, he was fascinated by the semiaquatic rodent and pond life. When he did a book about wolves, he drew upon decades of encounters with wolves in Algonquin. But he also can be just as enthralled when watching — and trying to take pictures of — a crab spider.

“I truly appreciate every living thing at its own level, for its own face value,” says Runtz. “It gives me great pleasure, not just looking at animals, but also learning about them, watching them firsthand and making observations.

“Every single time I go out in Algonquin, I learn something new.”

Even when Runtz doesn’t capture the images he was hoping for — when he spends six hours holed up in a blind unsuccessfully waiting for moose or bears or wolves to happen by — he’s never disappointed. Because he’s outside, totally immersed in nature, and there’s always an opportunity to see something interesting or new.

And while he prefers the cold of winter to the heat of summer, he doesn’t mind the black flies and mosquitoes that take over the bush in the warmer months.

“I consider those fellows the price of admission,” says Runtz. “Even when they’re biting me, it’s worth it.”

Experiencing the Complexity of Natural Systems

At Carleton, Runtz is known for getting his students outside as often as possible.

This term, he’s teaching a fourth-year ornithology course, a second-year class on the natural history of Ontario, and an online first-year natural history course — reaching a total of about 1,100 students.

With all the classroom and video teaching he’s done at Carleton — which in the early days involved mailing VHS tapes — Runtz estimates that he’s had more than 60,000 students. But regardless of what, when and how he’s teaching, his goals have remained constant.

Runtz wants students outdoors to spend time so they can experience first-hand how complex natural systems are, and so they discover how accessible nature is, even in a city like Ottawa.

“Getting them outside is critical,” he says, adding that some of his students had never seen a sunrise before taking one of his classes — unless it’s on their way home after a night out. “The drive to preserve something comes from appreciating it, and that appreciation comes from personal contact. It’s gratifying to see that spark of interest.”

Runtz encounters former students frequently. When he had to renew his permit for having one of Canada’s largest collections of mounted bird specimens, an ex-student with the Canadian Wildlife Service turned out to be the right person to reach. When he flew back home recently, an ex-student working for the Canada Border Services Agency inspected his luggage at the airport.

Sometimes, an arts student will take one of his classes as an elective, and then end up doing a master’s or PhD in Biology en route to a career in ecology or natural history.

“Michael’s encouraging and enthusiastic approach to his teaching, and his kind and affable approach with students, makes him very special,” says Jon Ruddy, who took a fourth-year ornithology taxonomy with Runtz in 2011, despite not being a Biology major, and now works as a birding guide.

“I promised Michael that I’d pull my weight and keep up with study and assignments. He permitted me to register for the course. Over the course of four months, we began to bond over our shared love of birds — mine, very new; his, a life-long affair. Michael encouraged me to continue with my interest in birds and consider a professional route, such as seeking summer work as a field ornithologist.

“Michael and I began to bird watch together outside of regularly-scheduled laboratory sessions and that’s when I really started to develop my skillset,” says Ruddy. “To have a renowned naturalist and very talented field birder completely to myself was one of the great blessings of my professional life. Michael is so very well-liked and loved by his students for his enthusiasm, generosity and inspirational teaching method. He’s the single best memory I have of my time at Carleton, no question!”

A Great Campus for Nature

Beyond field trips to trails on the outskirts of the city, where Runtz gets students to look at bird species distribution and anthropogenic impacts on habitat, among other lessons, he also leads a weekly nature walk on campus that’s open to the public.

It starts at 7:30 a.m. every Tuesday at the birdfeeders outside the Nesbitt Biology Building and heads either east along the Rideau River to Brewer Park, or west along the river and across the canal to the Fletcher Wildlife Garden.

As many as 15 to 20 people join the walk, which typically runs from early September until final exams in April. Sometimes only one other person turns up, but Runtz, who brings his camera and extra binoculars, says he’s never alone.

On these walks, he has seen bald eagles and peregrine falcons, owls and otters, hawks and minks, and too many pileated woodpeckers to count.

Last fall, the group heard a Cooper’s hawk making its monkey-like alarm call, and when they approached they saw the bird screaming at a barred owl in a pine tree. Half an hour later, in a thicket, they saw a mink killing a cottontail rabbit.

“I’ve never been disappointed on any outing here,” says Runtz. “Carleton has a great campus for nature.”

And a great guide for showing us how to appreciate it.

Michael Runtz will be giving a two-hour lecture about the natural history of Algonquin Provincial Park as part of Carleton’s Learning in Retirement Program on Tuesday, June 11 at 6 p.m. For more info and to register, please click here. He will also be lecturing about the natural history of Northern Ontario the following morning — for info, go here.

Tuesday, April 16, 2019 in Faculty of Science

Share: Twitter, Facebook