By Jonathan Malloy

The political power of the American Christian right naturally leads to interest and speculation about the influence of similar groups in Canada. But social conservatives and evangelical Christians are a marginal force in Canadian politics, even in the Conservative party. And research finds their dynamics here are quite different than in the United States.

Is there a Canadian Christian right at all? Yes and no.

The Christian right is closely associated with evangelical Christianity, and perhaps 10 to 15 per cent of Canadians (depending on the survey method) are evangelical Christians. Nearly all are strongly conservative on issues of reproduction and sexuality. But their broader political views vary considerably. Few would support “dominionist” ideas of imposing a theological state.

Furthermore, comparative research on American and Canadian evangelicals consistently finds different approaches to politics and political activity. In one striking study, American faith researcher Lydia Bean embedded herself (with full disclosure) in theologically similar church congregations in Buffalo, N.Y., and the Ontario city of Hamilton — only 100 kilometres apart — and found clear-cut political differences.

While all were strongly anti-abortion, the Buffalo group was heavily right-leaning across the board. They were also suspicious of government and secular society. In contrast, the Hamilton congregation was ideologically different beyond social conservatism. They were also more supportive of public institutions and accepting of different opinions.

Different political systems

Access to power also differs in the two countries. The Canadian parliamentary system concentrates power top-down in government and party leaders. The more bottom-up American system gives greater openings for legislators to pursue independent agendas.

This was evident under Stephen Harper’s Conservatives. While sometimes accused of having a theological agenda himself, Harper openly stopped attempts by backbenchers to introduce abortion-related bills and motions. Current Conservative Leader Andrew Scheer has pledged to follow Harper’s lead and not reopen the abortion issue.

This is not to say there isn’t an evangelical and social conservative streak in the Conservative party. Scheer may give more freedom to backbenchers than Harper did. The strongly anti-abortion Brad Trost came fourth in the 2017 leadership race. Yet Conservatives have shown little interest in advancing abortion rights any further.

Provincial governments have rolled back progress on sex education and gay-straight alliance clubs. But provincial party leaders retain strong top-down control. And they seem to prefer to avoid rather than engage in these issues, even when they’re facing pressure from within their parties.

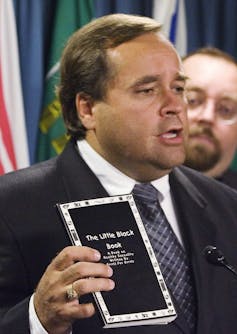

In this landscape, Canadian activism can be divided into two camps. The first is small but loud. Its most prominent figure is Charles McVety, president of Canada Christian College and associated with the rollback of the sex education curriculum in Ontario. But while skilled in cultivating publicity, McVety’s exact influence with either government or fellow evangelicals has never been clear.

In contrast, groups in a larger second camp keep a lower profile. The largest evangelical Canadian organization, the Evangelical Fellowship of Canada (EFC), avoids protests and partisan engagement. While firmly socially conservative, the EFC engages on a broad range of issues that go beyond Christian right ideas. For example, it has taken a strong stand against Bill 21 (banning religious symbols) in Québec even though the legislation will have little effect on evangelicals.

Fighting defensively

The American Christian right is powerful and dominates politics in some parts of the United States. But Canadian activists are primarily fighting defensive battles.

A good example is the recent controversy over the Canada Summer Jobs program. Last year, Justin Trudeau’s government introduced new requirements for organizations seeking summer job subsidies to affirm their adherence to Charter of Rights and Freedoms values. This was clearly directed at anti-abortion groups that in the past had received subsidies for summer students.

But the wording of the application ensnared all religious applicants that held anti-abortion views.

Another example is the unsuccessful attempt of B.C.-based evangelical Christian Trinity Western University to accredit their new law school, with its restrictive “lifestyle covenant” that binds students to a code of conduct that includes abstinence from sex outside of heterosexual marriage (now removed) — even though its teachers program already had such a covenant requirement.

In both cases, the evangelicals’ challenge was to preserve their previous ability to exercise their views and values in semi-public spaces. And as secularization increases in Canada, this could lead to further encroachments on that space, such as the removal of charitable tax status for churches.

Sophisticated groups like the Evangelical Fellowship of Canada are therefore adopting a broad religious freedom agenda that links their struggles with other religious rights issues, such as the ban on religious symbols in Québec.

Despite their bluster on reproduction and sexuality issues, Canadian evangelicals are on the defensive. And the Conservative Party of Canada has done a masterful job retaining evangelical support despite not delivering on their key priorities.

So while there’s something resembling a Christian right in Canada, its influence is limited and the context quite different from the United States. It does have policy successes, but not many. The broader picture is one of marginal influence and largely defensive battles.

While they’re not going away, evangelicals and social conservatives in Canada are distinctly different from the American Christian right.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Carleton University is a member of this unique digital journalism platform that launched in June 2017 to boost visibility of Canada’s academic faculty and researchers. Interested in writing a piece? Please contact Steven Reid or sign up to become an author.

All photos provided by The Conversation from various sources.

![]()

Sunday, August 11, 2019 in The Conversation

Share: Twitter, Facebook