Lead image by gorodenkoff / iStock

By Dan Rubinstein

Astrocytes are the best cells in the brain.

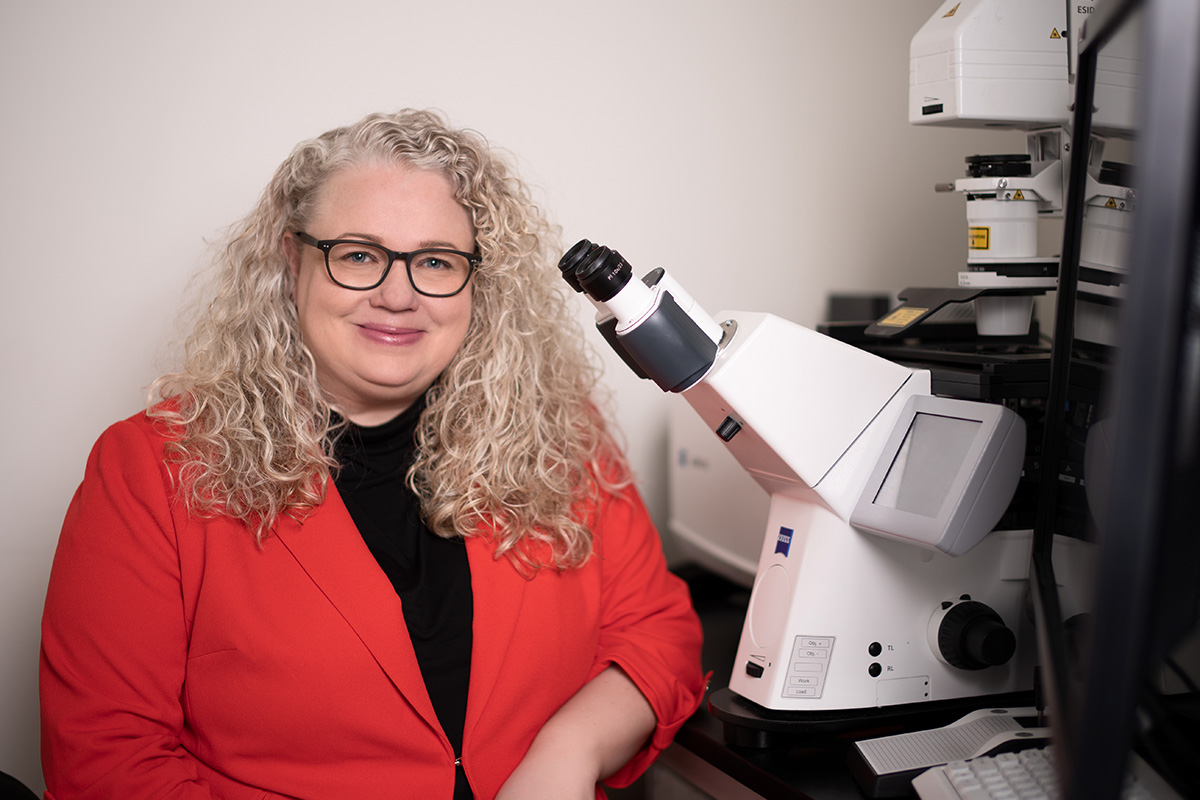

At least that’s the verdict of Carleton University’s Natalina Salmaso, the Canada Research Chair in Behavioural Neurobiology.

So named because of their star-like shape, astrocytes are glial cells found in the brain and spinal cord. More than half of the brain’s cells are “glial,” a descriptor derived from the Latin word for glue because it was once thought that these cells held neurons in place.

Now we know they do so much more, which is why Salmaso is smitten with the “beautiful” astrocyte. It’s the most abundant cell in the human central nervous system and is linked to the blood-brain barrier, a layer of cells that protects the brain from harmful substances.

Canada Research Chair in Behavioural Neurobiology Natalina Salmaso (Photo by Lindsay Ralph)

The end-feet of astrocytes — the terminal projections at the tip of each nerve fibre — basically fill gaps called tight junctions in blood vessels found in the brain.

“They can change the permeability for things getting in or out, including nutrients and stress hormones,” explains Salmaso.

“They’re sitting at this important interface and modulating all the connections between neurons.”

Astrocytes are central to Salmaso’s research, which is focused on neuropsychiatric disorders such as anxiety, depression and Parkinson’s disease. Because these cells appear to protect the brain, she is exploring whether they can be activated preventively, before symptoms emerge, to reduce the cumulative damage that causes debilitating health conditions.

“The more I study astrocytes, the more I realize that they’re critically involved in everything in the brain,” she says. “We have to think of the brain as an integrated cellular system.”

Early Detection and Intervention

Mood disorders like depression and anxiety are part of the prodrome — or early set of symptoms — of Parkinson’s. About a decade before the tremors, muscle stiffness and loss of balance typically associated with the disease manifest, changes in the brain can lead to psychological warning signs.

As with many medical conditions, early detection and intervention can help delay onset and preserve quality of life.

Salmaso, whose main research interest is brain development, knows that neuropsychiatric diseases are very complex. Individuals can have a genetic vulnerability to a particular ailment, but “life antecedents” such as stress or premature birth also contribute to susceptibility.

This ties into the concept of “allostatic load” — the idea that the more negative “hits” you have, the more likely you are to develop a neuropsychiatric disease, while on the other hand, growing up in a healthy environment with a supportive family and good school (or similar positive factors) could make you more resilient.

“We’re interested in looking at how the brain develops and learning more about what moves it in one direction or the other,” says Salmaso, “and building models that include genetics, stresses, environment and so forth.”

Which brings us back to astrocytes.

Although first identified about a century ago, researchers only began to zoom in on these cells in the last few decades.

Initially, they were seen as “kind of first responders to an injury,” says Salmaso. For example, they will form a glial scar in areas of the brain that are damaged by a stroke.

Astrocytes were thought of as largely dormant, springing into action as needed. Now Salmaso are her team are trying to figure out how to “turn them on” them before neuropsychiatric symptoms develop, as opposed to later in response.

Keeping the End User in Mind

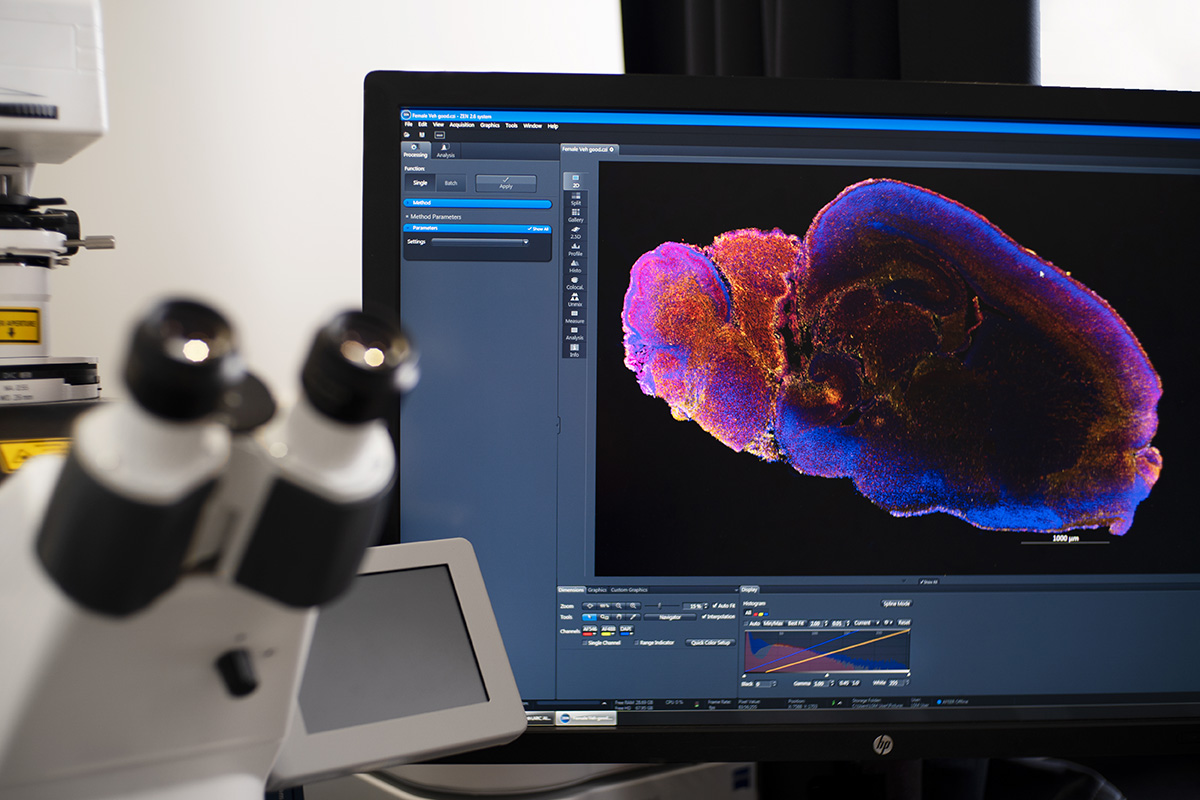

Like the neuropsychiatric diseases she studies, Salmaso’s wet-lab experimentation is also very complex.

It involves modifying astrocytes with a gene that’s sensitive to stimulation from a particular wavelength of light. An optic probe can be inserted into that region of the brain and the astrocytes there can be activated.

While cells are being cultured in the lab and there is some digital modelling, animal models are used because there are potential human health benefits. Ultimately, a drug that contains a molecule that activates astrocytes could be developed.

The single cell RNA sequencing that Salmaso is doing these days may be closer to fundamental research than pharmaceutical intervention, but she and her students keep “end users” in mind.

Their work has been supported by Parkinson’s Canada and the Parkinson Research Consortium, and they’ve participated in public events and given talks to patient groups.

“We’re very connected to that community and on the public health front,” says Salmaso.

“As our population ages, a very large number of people will be vulnerable. Unless we come up with ways to intervene earlier, it’s going to be tough on a lot of people.”

Second wide image by Jacob Wackerhausen / iStock

Friday, March 21, 2025 in Faculty of Science, Neuroscience, Research

Share: Twitter, Facebook