By Anthony Q. Briggs and Warren Clarke

In 2018, Black people globally got a signal of hope when director Ryan Coogler and Marvel Studios released the critically acclaimed movie, Black Panther. While few knew of the Black Panther as a superhero despite the comic being released in the 1960s, millions now know of him because of the film’s overwhelming success.

Its success can be due, in part, because of what it tells us about Black people’s futures. Many Black people — seeking belonging and better outcomes for their lives — have turned to afrofuturism as the source of optimism. According to afrofuturist expert and author Ytasha Womack, afrofuturism refers to “an intersection of imagination, technology, the future and liberation … Afrofuturists redefine culture and notions of Blackness for today and the future by combining elements of science fiction, historical fiction, speculative fiction, fantasy, afrocentricity and magic realism with non-western beliefs.”

Black Panther had Black people chanting “Wakanda Forever,” while many imagined that they too could put on the Black Panther suit to gain a sense of belonging. Black people, including Canadians, believed that Wakanda, the utopian city where the Black Panther resides, is a real place. For Black Canadians, Wakanda offers a place that exists outside the harsh reality of an anti-Black white settler narrative that is anti-Black.

Black legal scholar Lolita Buckner Inniss says anti-Black racism is deeply enmeshed in the Canadian social fabric. Anti-Black racism cuts deep enough so that many, if not all, Black Canadians feel there is no hope for a better future.

Leaving family but not tradition

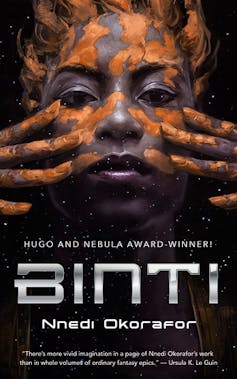

Afrofuturism in cinema is but one source. Writer Nnedi Okorafor’s 2015 science fiction novella, Binti, features a Black woman protagonist named Binti Ekeopara Zuzu Dambu Kaipka. Binti is an intelligent woman leader of the Himba tribe whose genius gets her into to the prestigious Oomza University, which floats about the galaxy. Binti is the first member of the Himba ethnic people to attend the school. Her decision to attend is met with ridicule, laughter and threats to her life due to the fear and insecurities of her people.

Her people have never been allowed to imagine futures beyond their traditional way of life and identification with the land. Binti states:

We Himba don’t travel. We stay put. Our ancestral land is life; move away from it and you diminish. We even cover our bodies with it. Otjize is red land. Here in the launch port, most were Khoush and a few other non-Himba. Here, I was an outsider; I was outside.

She echoes the social challenges that Black people face when embarking upon new ways of living after leaving traditional family and cultural contexts. Often, their families and cultures pressure them to remain entrenched within the known confines of family, culture and community, rather than explore the new and unknown.

One of us, Anthony, was the first member of his immediate family to attend post-secondary education and graduate school. He wanted to apply to graduate school but had to fight internalized feelings of low self-worth that insisted he did not belong in academia. Indeed, a lack of self-confidence influenced the choice to avoid applying to programs that required a high grade-point average with a full scholarship because he did not believe he would be accepted.

Blazing a trail to a Black future

In her village, Binti had been one of the few who used knowledge to create peace in her tribe, so she had to overcome pressure to remain in the village in order to embrace new learning. On a spaceship, travelling from her village to the Oomza University, Binti as the only Himba at the university encounters another obstacle: the false assumption that people from her land are evil, dirty and primitive.

In one moment, one of the Khoush (a different lighter-skinned tribe) students touches Binti’s braids out of curiosity and without consent. Her hair is mixed with sweet smelling red clay and perfume called Otijze, which is connected to her cultural heritage. One of the Khoush students responds that it has a horrible smell, suggesting a passive discriminatory logic of sanitation.

One can observe strong echoes of the attitudes of privileged whites towards high-priority Black neighbourhoods whose inhabitants are stereotyped as criminal, irrational, impoverished and unintelligent. The book suggests that there is no such thing as neutral space and that structural inequities and racial inequalities make space and place difficult to navigate, especially in elitist environments.

But Binti is gripped by the challenge of the new. Her journey of self-discovery begins when she decides to leave village life, defying her ancestors’ dedication to their land and cultural identity. Binti explains that tribal knowledge was handed down orally as her father had taught her 300 years of oral lessons “about astrolabes including how they worked, the art of them, the true negotiation of them, the lineage … circuits, wire, metals, oils, heat, electricity, math current and sand bar.” Her mother had also transmitted mathematical insights and gifts, but never in formal educational settings. Family unity and protection were paramount.

Binti symbolizes the trailblazer who encounters politics, racism, stereotypes, ignorance, systemic inequalities, gender inequities, classism and so on. Additionally, she faces the strong pull of past traditions since she is the first member of her family and tribe to attend a formal educational institute.

Some Black individuals living such stories will inevitably encounter feelings of isolation, lack of belonging and self-doubt. Their internal battles will pit self-trust and the drive towards the new against the safety and security of the past. They will have to develop a secure sense of self and an understanding that it does not matter how far they travel among the galaxies because everyone has unique gifts they can contribute to the universe.

Against the pull of anxieties and insecurities, Anthony graduated with a master’s degree and a PhD; he currently has a post-doctoral fellowship — yet is in another galaxy of his own among the stars.

Afro-Caribbean Black people living in white settler, colonized nations such as Canada face discrimination and negative stereotypes. Afrofuturism can enable Black communities to reimagine new possibilities, especially when the future trajectory for Black Canadians is at times uncertain.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Carleton University is a member of this unique digital journalism platform that launched in June 2017 to boost visibility of Canada’s academic faculty and researchers. Interested in writing a piece? Please contact Steven Reid or sign up to become an author.

All photos provided by The Conversation from various sources.

![]()

Tuesday, February 18, 2020 in The Conversation

Share: Twitter, Facebook