Canadians are anxious for the eventual availability of a COVID—19 vaccine that will protect public health and provide some level of confidence that it is safe to return to pre-pandemic activities. But new research suggests a global pandemic has not swayed the opinion of some Canadians who are vaccine hesitant, and may not get vaccinated against the novel coronavirus should a vaccine be developed.

While a majority of Canadians express confidence in the safety and effectiveness of vaccines, increasing numbers of people report concerns about vaccine safety and effectiveness. Research pegs Canada’s “vaccine hesitancy” rate at approximately 20 percent. In 2019, the World Health Organization called vaccine hesitancy one of the 10 most serious threats to global public health.

Where do Canadians stand on the benefits of a vaccine for COVID—19?

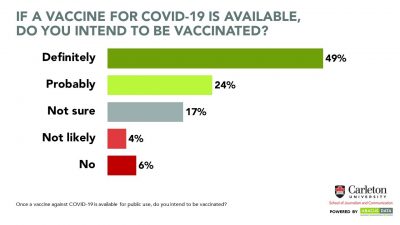

Researchers in the School of Journalism and Communication at Carleton University, in partnership with Abacus Data, recently completed a national survey of 2,000 Canadians which found that a strong majority of respondents said they would “definitely” (49 per cent) or “probably” (24 per cent) accept a COVID vaccine once it is publicly available. By .contrast, 10 per cent said they would “definitely not” (six per cent) or “not likely” (four per cent) get a vaccine, and an additional 17% expressed uncertainty. In short, more than one-quarter of Canadians oppose a vaccine or remain hesitant about whether they would accept it for themselves.

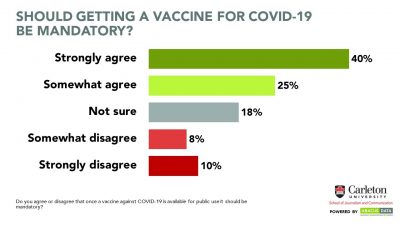

When asked whether a COVID vaccine should be mandatory for people in public-facing occupations, two-thirds of all respondents expressed agreement. Among those who expressed an intention to be vaccinated, almost all of them (98 per cent) believe that a coronavirus vaccine “should be mandatory”. However, among those who say they will not accept to be vaccinated, 75 per cent said they “strongly disagree” with making a COVID vaccine mandatory.

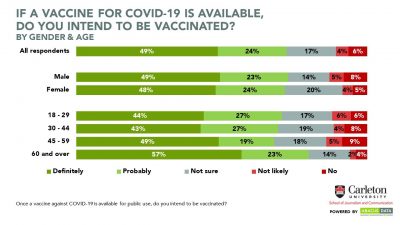

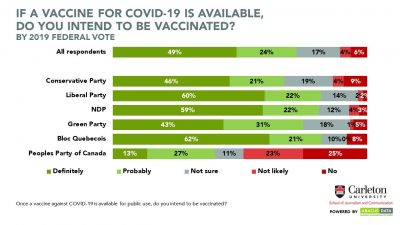

Although gender was not an important predictor of vaccination intention, other factors were significant, including age and political affiliation. Perhaps not surprisingly, given the differential demographic impacts of coronavirus infections, older Canadians were more likely than younger Canadians to say they would accept a vaccine when it becomes publicly available. Respondents who expressed a strong intention of accepting a vaccine were more likely to vote Liberal or NDP than to support other parties.

Among those who hold strong views against vaccination, 30 per cent identify as Conservative, compared with 9 per cent who identify as Liberal, three per cent as NDP and seven per cent as Green Party supporters (10 per cent identified with “another party” and 42 per cent said they do not identify with any single party). The survey also asked Canadians about their beliefs in health myths and conspiracy theories regarding COVID—19. Almost half (46 per cent) of all survey respondents said they believe at least one of the four statements tested. Among this group, 16 per cent say they are not likely or not going to get vaccinated for COVID—19 if a vaccine becomes available. That’s 10-percentage points more likely than those who do not believe one of the scientifically inaccurate claims about COVID—19. They are also almost twice as likely to disagree that vaccination should be mandatory (23 per cent compared to 12%).

There did not appear to be a statistically important relationship between which province respondents lived in and vaccination intentions or views, although respondents living in Atlantic Canada showed the strongest levels of intention to vaccinate than those in other parts of the country (respondents in this region also report higher levels of seasonal influenza vaccination). On the other hand, Canadians who live in urban or suburban communities were seven percentage points more likely than those who live in rural parts of the country to say they would definitely be vaccinated, and five percentage points more likely to support mandatory vaccination.

Josh Greenberg, professor of communication and media studies and one of the project co-investigators, says “these results clearly point to the need for a serious public conversation about vaccination in general, and the roll out of a COVID—19 vaccine in particular.” Greenberg argues that such an initiative “should begin now, before a vaccine becomes publicly available.” He notes that anti-vaccination groups are already weaponizing misinformation on social media, bracing for the inevitable information war that will accompany the anticipated availability of a COVID vaccine. “It’s incumbent on elected officials and public health experts to be proactive, to build trust among Canadians using effective methods of risk communication, and to really sharpen their social media ground game.”

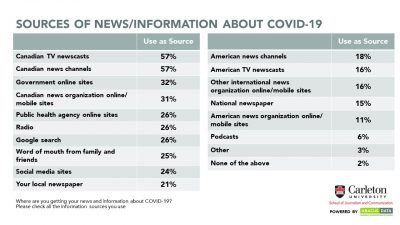

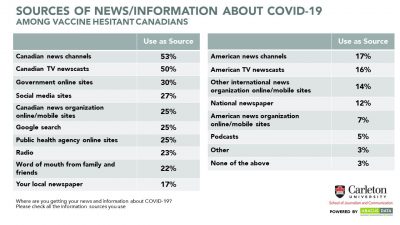

The survey also explored questions about where Canadians are getting their COVID—19 news and information. The researchers found that among Canadians holding vaccine hesitant views, television newscasts and news channels in general were by far the most commonly identified source of COVID information (50 per cent and 53 per cent, respectively). Other media, including radio, mobile news apps, social networking sites and government/public health websites, are also accessed by vaccine-hesitant Canadians, although far less often.

Among those who expressed vaccine-hesitant views (i.e., those were “not sure” whether they would get vaccinated), 74 per cent said they were very or somewhat interested in health and science news stories and 60 per cent said they were very or somewhat interested in media stories that debunk conspiracy theories or unscientific arguments.

Sarah Everts, CTV Chair in Digital Science Journalism and one of the study’s co-investigators argues that television news can play an important role in shaping how the public makes sense of how vaccines figure in relation to their understanding of the pandemic. “Television reports that debunk conspiracy theories and can deliver scientifically accurate, visually compelling narratives are most likely to reach individuals who are hesitant about a COVID—19 vaccine,” she says. Everts argues that public health agencies at all levels of government “must prioritize the development of visually strong and engaging public communication materials, especially videos and interactive media, that can advance scientifically accurate information about the nature and scale of risks posed by COVID—19.”

Notes on Methodology:

The public opinion survey noted above is a project of the School of Journalism and Communication at Carleton University, supported by Abacus Data. A second phase of the survey will be conducted in early June, with a comprehensive report to follow.

The first phase of the survey was conducted with 2,000 Canadian residents from May 5-8, 2020. The margin of error for a comparable probability-based random sample of the same size is +/- 2.19 per cent, 19 times out of 20.

The data were weighted according to census data to ensure that the sample matched Canada’s population according to age, gender, educational attainment, and region. Totals may not add up to 100 due to rounding.

For more information:

Josh Greenberg, PhD

Professor

School of Journalism and Communication

Carleton University

joshua.greenberg@carleton.ca

Sarah Everts

CTV Chair in Digital Science Journalism

School of Journalism and Communication

Carleton University

sarah.everts@carleton.ca

Thursday, May 21, 2020 in News Releases

Share: Twitter, Facebook