While Canadians remain quite worried about the impact of COVID-19 on their lives and those of their friends, they place primary trust in the actions taken and advice given by the country’s public health authorities and institutions to guide the country through the pandemic.

That’s one of the conclusions from a Carleton University School of Journalism and Communication survey of the attitudes of 2,000 Canadians to health information and the media conducted by Abacus Data from May 2 to May 8.

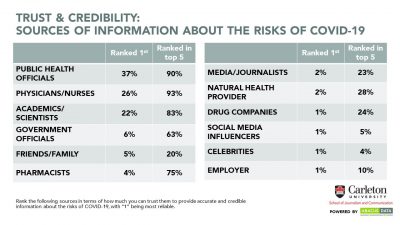

Asked to rank a series of sources based on how much they can trust them to provide accurate and credible information about the risks of COVID-19, public health officials came first, the top choice of 37 per cent of respondents.

“Trust in the medical community may be related to the concern that many Canadians have that they will become seriously ill with the virus,” says Christopher Waddell, a professor in the School of Journalism and Communication one of project’s co-investigators.

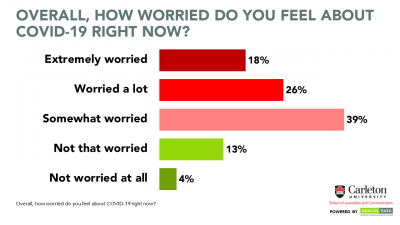

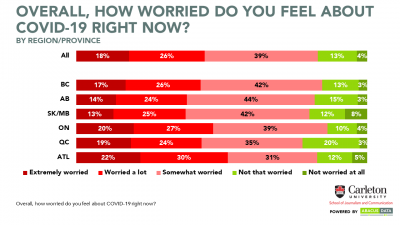

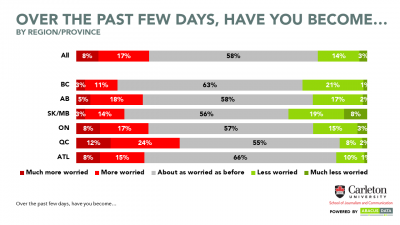

When asked their views on the COVID-19 outbreak, 39 per cent across the country believed the worst was still to come, 19 per cent thought the worst was behind us, while 42 per cent were not sure – with almost half of those surveyed still extremely worried or worried a lot.

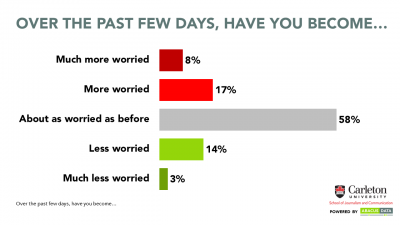

That view that had not changed significantly in early May for more than half of Canadians.

While worried, they also have high confidence in the ability of their local health-care system to handle the outbreak, with 19 per cent very confident nationally and a further 61 per cent somewhat confident.

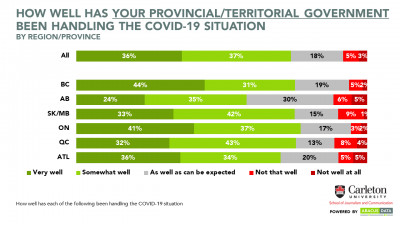

Canadians also rank the performance of the three levels of government differently in handling the COVID-19 situation. Provinces have done the best so far in the eyes of the public, with 36 per cent saying their provincial/territorial government has done very well and an additional 37 per cent saying somewhat well.

That may not be surprising considering the daily appearances of provincial health officers on Canadian news channels offering updates and briefings on cases, hospitalizations, ventilator demand in hospitals, deaths and recoveries. Some, including British Columbia’s Provincial Health Officer Bonnie Henry and Horacio Arruda, Quebec’s director of National Public Health, have become social media celebrities since early March.

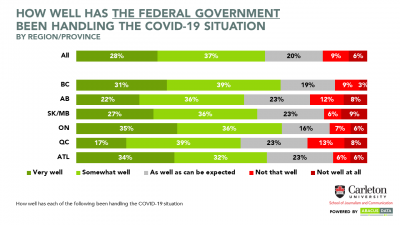

The federal government has handled the situation very well, say 28 per cent of Canadians, with another 37 per cent saying somewhat well. Theresa Tam, the country’s chief public health officer, has been as prominent as some of her provincial colleagues, but has also become more of a target for political and media critics. They have attacked her for changing advice about wearing face masks and a Conservative leadership candidate was widely condemned for his suggestion that the Hong Kong-born doctor’s loyalty may rest with China rather than Canada.

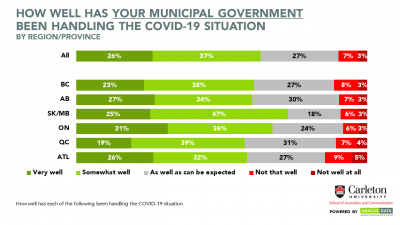

Municipalities scored lowest among the three layers of government, with 26 per cent believing they are handling the situation very well and another 37 per saying somewhat well. Urban municipalities have been the focus of complaints that parks and recreation space has not been accessible and demands to close roadways to vehicles, allowing more cyclists and letting pedestrians venture onto roads to maintain physical distancing.

Canadians also give public health officials high marks for their performance to date during the pandemic. Just more than 80 per cent credit them with performing very well or pretty well in being forthcoming with the public about the risks associated with COVID-19, while 85 per cent are pleased with the frequency of official updates about the virus.

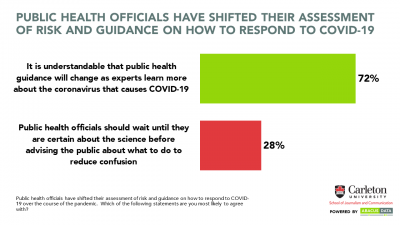

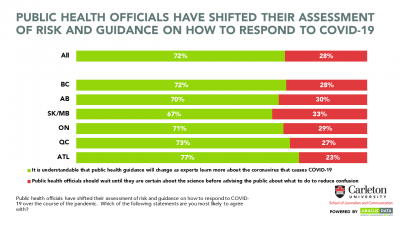

“The public also appears to appreciate the evolutionary nature of science and health knowledge,” says Waddell.

Almost three-quarters of respondents agreed with the statement: “It is understandable that public health guidance will change as experts learn more about the coronavirus that causes COVID-19.’’ Only 28 per cent agreed with the statement: “Public health officials should wait until they are certain about the science before advising the public about what to do to reduce confusion.” That statement was supported by 34 per cent of men but only 22 per cent of women.

Notes on Methodology:

The public opinion survey is a project of the School of Journalism and Communication at Carleton University funded by its Faculty of Public Affairs and supported by Abacus Data. A second phase of the survey will be conducted in early June, with a comprehensive report to follow.

The first phase of the survey was conducted with 2,000 Canadian residents from May 5 to 8, 2020. The margin of error for a comparable probability-based random sample of the same size is +/- 2.19 per cent, 19 times out of 20.

The data were weighted according to census data to ensure that the sample matched Canada’s population according to age, gender, educational attainment, and region. Totals may not add up to 100 due to rounding.

For more information:

Christopher Waddell, Ph.D.

Professor

Program Director

Bachelor of Media Production and Design

School of Journalism and Communication

chris.waddell@carleton.ca

Friday, May 22, 2020 in News Releases

Share: Twitter, Facebook