By Lisa Gregoire

Photos by Lisa Gregoire

If it’s true what Ernest Hemingway said, that the world breaks us and makes us strong in the broken places, then Inuit in Canada are primed to lead us into an uncertain future.

That is if those in power, who have controlled or silenced Inuit voices for decades, stop talking and listen.

That was a recurring theme at this year’s Kinamàgàwin Symposium, a sold-out, virtual summit on Feb. 25, 2021 of Inuit scholars, advocates and performers hosted by Carleton University’s Centre for Indigenous Initiatives.

Martha Flaherty

True to its title—The Inuit Relocations: Intergenerational Impacts and Inuit Resilience—the event highlighted the High Arctic government relocation of Inuit families in the 1950s with painful recollections from keynote speaker and survivor Martha Flaherty. It’s a chapter of history that is perhaps not well known by many.

“Earlier in my years, I thought that the worst enemy of truth was lies,” said Carleton President Benoit-Antoine Bacon.

“I’ve come to understand that silence is perhaps an even greater enemy.”

After Flaherty described the impacts of the Crown’s egregious human experiment on Inuit, the focus of the event shifted toward identifying and overcoming barriers that today prevent Inuit from realizing self-determination.

Megan Dicker Nochasak, a 22-year-old Inuk from Nain, Labrador, captured the essence of that pivot with a favourite quote during a student panel discussion. “Teach Indigenous experience and success as much as, or more than, you teach Indigenous suffering and trauma,” she said.

Inuit Identity, Culture and Education

Despite the technological challenges of hosting an online event during a pandemic—aggravated by notoriously poor northern phone and Internet service—the symposium was relatively seamless and included an array of pre-recorded Inuit cultural performances.

Benny Michaud

The day began with Elder Aigah Attagutsiak lighting the qulliq, a traditional bowl-shaped oil lamp, and concluded with youth discussing Inuit identity, culture and education. This trajectory, from past to future, was not lost on Benny Michaud, director of the Centre for Indigenous Initiatives, and the symposium’s host.

“If we want to move forward, we have to turn around and look back at where we come from, who we are and where we’ve been, and I think that’s what we’re doing when we bring people together, like we have today.”

Katherine Minich

The morning’s agenda included a panel of three Inuit women who are overcoming systemic obstacles to incorporate Inuit traditions and world views into mainstream life, work and government policy.

Pangnirtung-born Katherine Minich, a lecturer and Bruce Fellow Scholar from Carleton’s School of Public Policy and Administration, for example, talked about her research efforts to reframe public policy-making in northern communities by centring the discussion around Inuit social values and by striving to reduce community harm and bolster community health.

Dean Peesee Pitsiulak

Peesee Pitsiulak, dean of Education, Inuit and University Studies at Nunavut Arctic College in Iqaluit, talked about the ongoing struggle to incorporate Inuit language and culture in northern school curricula and course materials—a nagging vestige of colonialism and Inuit disempowerment.

The afternoon’s agenda offered hundreds of virtual attendees a hopeful future, starting with a rousing call to action from Inuit rights advocate and climate change educator, Sheila Watt-Cloutier, who spoke on the interconnectedness of the environment, the economy, global foreign policy, sustainability and human rights.

Sheila Watt-Cloutier

But perhaps the most uplifting moments came toward the end of the day, during the youth panel hosted by moderator Aliqa Illauq, a student in Carleton’s Law and Human Rights program.

All four panellists, currently enrolled in virtual studies in Ottawa and Montreal, offered insights into the role traditional culture plays in their lives and what it means to be an Inuk in Canada today.

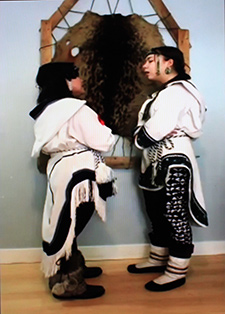

Throat-singing duo Tarniriik—Cailyn Degrandpré and Samantha Kigutak-Metcalfe

“It’s strange, connecting to my culture has definitely helped slow down the stress of this modern world,” said Siku Rojas, 18 and living in Iqaluit.

“It’s really helped in getting comfortable with what Nunavut is becoming. We’re such a young territory. We need to learn how to grow.”

Lexie Padluq, originally from Kimmirut, Nunavut, said her culture makes her “a better version of herself.” Knowing how her ancestors used resiliency and ingenuity to thrive outdoors in such a harsh climate makes her proud of her roots and passionate about helping the next generation succeed.

“In the future, I want to see more unapologetic Inuit, standing up for their rights and not accepting anything less than anyone else,” Padluq said, “doing what they want, mixing modern and Inuit culture.”

This year’s Kinamàgàwin Symposium was conceived of and organized by a student committee consisting of Carissa Metcalfe-Coe, Donovan Gordon-Tootoo, Aliqa Illauq, Alejandra Metallic-Janvier and Ann Seymour from Carleton..

Kinamagawin Symposium Youth Panel

Monday, March 1, 2021 in Events, Indigenous

Share: Twitter, Facebook