Conspiracy theories and incorrect scientific information about Covid-19 have taken root in Canada, according to a recent survey conducted by the School of Journalism and Communication at Carleton University. Nearly half of Canadians (46 per cent) believed at least one of four Covid-19 conspiracy theories and myths addressed in the survey.

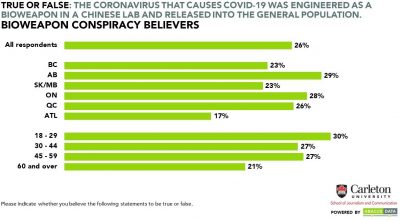

A quarter of Canadians (26 per cent) believe a widely discredited conspiracy theory that the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 was engineered as a bioweapon in a Chinese lab and released into the general population.

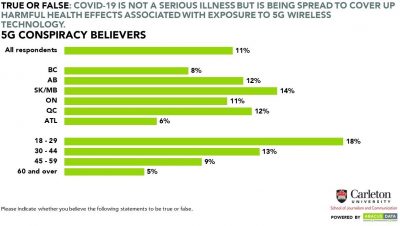

Likewise, 11 per cent of Canadians believe another conspiracy theory, that COVID-19 is not a serious illness but is being spread to cover up harmful health effects associated with exposure to 5G wireless technology. Police in Quebec are currently investigating whether arsonists responsible for setting ablaze multiple cell towers in the province were motivated by this conspiracy theory.

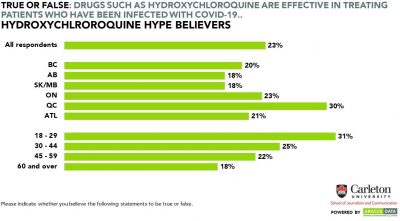

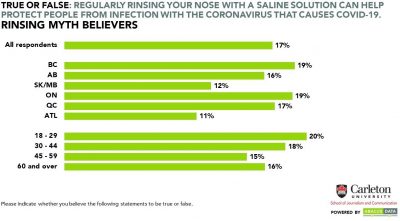

Moreover, more than one-fifth (23 per cent) of survey respondents believe the hyped and unproven claim promoted by U.S. President Donald Trump that drugs such as hydroxychloroquine are effective in treating patients who have been infected with COVID-19. And one-sixth of respondents (17 per cent) believe a myth that regularly rinsing your nose with a saline solution can help protect individuals from infection with the coronavirus that causes COVID—19.

Remarkably, over half of Canadians surveyed (57 per cent) were confident that they can “easily distinguish conspiracy theories and misinformation from factual information about COVID- 19.” Nearly half (49 per cent) of those who believe the bioweapon conspiracy theory, and 58 per cent of respondents who believe the 5G conspiracy theory, said they can easily distinguish.

“I was floored by the overconfidence Canadians have in their own ability to distinguish conspiracy theories and misinformation,” said Sarah Everts, CTV Chair in Digital Science Journalism, and a co-researcher on the study. “Everyone has fallen prey at some point to misinformation on social media. Anyone who thinks that it’s easy to distinguish conspiracy theories and misinformation is at high risk of being fooled.”

Younger individuals (aged 18 to 29) were slightly more likely to believe the conspiracy theories than older people surveyed. There was little regional difference, although respondents from Atlantic Canada were consistently less likely to believe the conspiracy theories than Canadians in other parts of the country.

Among other demographic criteria – such as gender, education level, and household income – there were similar rates of belief in conspiracy theories and pseudoscience.

The pervasive influence of misinformation on how Canadians talk about COVID—19 poses a serious risk communications challenge, says Josh Greenberg, one of the study’s co-researchers and a professor in the School of Journalism and Communication. “Our research surfaces one of the biggest risk communication problems during a pandemic,” he says. “Pseudoscience circulates quickly and can be difficult to track, so how do public health experts respond?”

The Carleton research doesn’t provide answers to this question, but Greenberg argues that scientists and public health experts must become more actively engaged in the public conversation about COVID—19 and “push back” on misinformation when they see it. “Public health experts need a more sophisticated social media ground game,” he says. “The best medicine for fighting health misinformation is more scientifically accurate information that is accessible, engaging and shareable.”

The Carleton study also found that individuals who believe the discredited conspiracy theories spend more time every day on social media platforms than those who don’t believe them. This held true on all platforms, including Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat, Instagram and Tiktok.

Survey respondents who believed the 5G and bioweapon conspiracies specifically were more likely to share news or opinion about Covid-19 on social media. They were also more likely to accuse others on social media of spreading misinformation, and they were more likely to be accused of spreading misinformation, than those who don’t believe the conspiracy theories.

“We all have a limited amount of time to spend online every day,” says Everts. “Our survey provides yet another data point to suggest that we should be very cautious about where we get our COVID news and information. Instead of scrolling through social media feeds where the potpourri of information ranges from trustworthy to downright dodgy, we should intentionally seek out reputable sources of COVID-19 news and information that contain insight and analysis from credible experts.”

Survey methodology

The public opinion survey is a project of the School of Journalism and Communication at Carleton University funded by its Faculty of Public Affairs and supported by Abacus Data. A second phase of the survey will be conducted in early June, with a comprehensive report to follow.

The first phase of the survey was conducted with 2,000 Canadian residents from May 5 to 8, 2020. The margin of error for a comparable probability-based random sample of the same size is +/- 2.19 per cent, 19 times out of 20.

The data were weighted according to census data to ensure that the sample matched Canada’s population according to age, gender, educational attainment and region. Totals may not add up to 100 due to rounding.

For more information:

Sarah Everts,

Associate Professor

CTV Chair in Digital Science Journalism

School of Journalism and Communication

Carleton University

sarah.everts@carleton.ca

Josh Greenberg, PhD

Professor

School of Journalism and Communication

Carleton University

Joshua.Greenberg@carleton.ca

Wednesday, May 20, 2020 in News Releases

Share: Twitter, Facebook